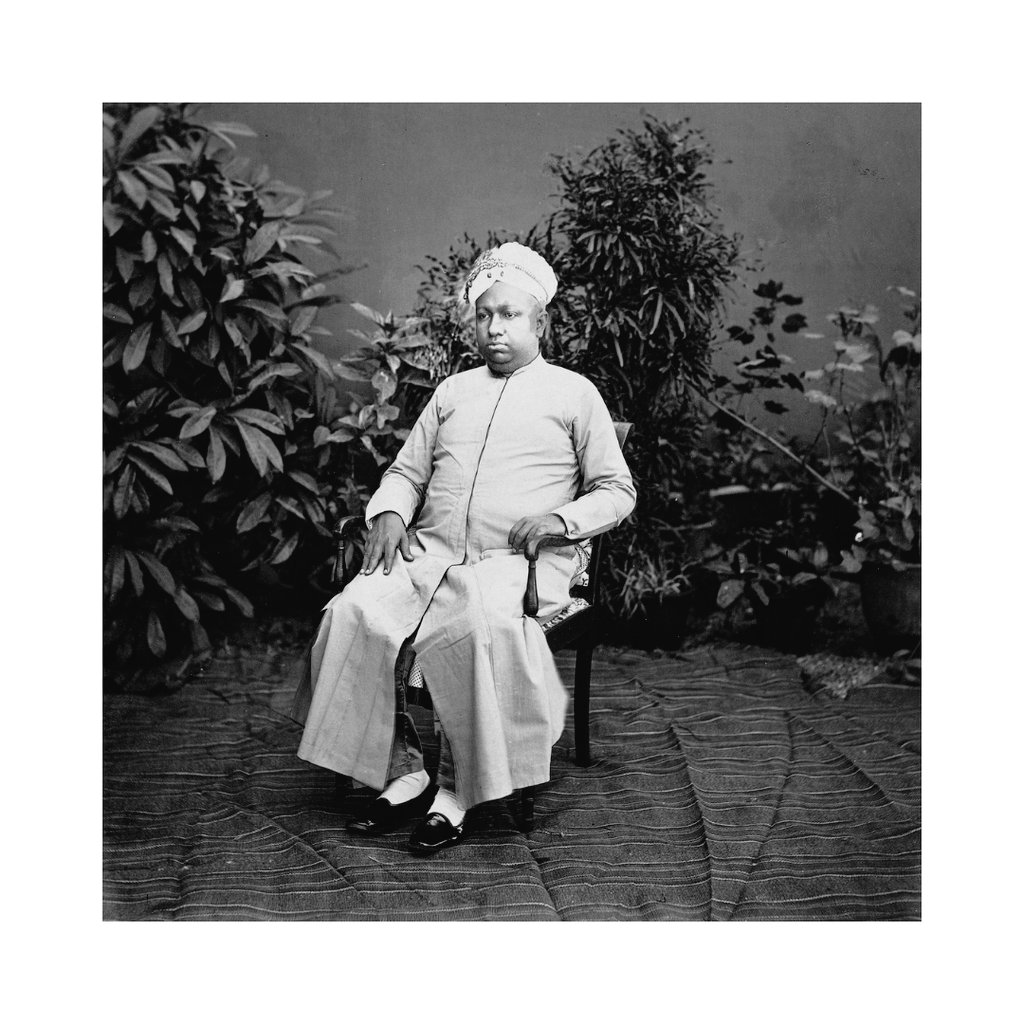

This man with the fancy moustache is Krishnaraja Wadiyar III (1794-1868) of Mysore. His story, as related in my new book #FalseAllies, encapsulates the complicated internal politics of a princely state, where the British & ruler were not the only factors..

Parked on the throne at 5, his govt was first run by an able minister called Purniah. But when the rajah grew up, Purniah hesitated to let him rule, calling him a 'foolish child'. Krishnaraja's first challenge, then, was to rid himself of the minister..

Then there was the British agent who felt he should be consulted on all things great and small, which the ruler refused. The third element was the bureaucracy: Mysore had a powerful class of Marathi Brahmins who dominated the civil service, and..

Krishnaraja's attempts to replace them with local men caused resentment. The 'foreign' Brahmins & British agent formed an alliance, checking the rajah's power. Interestingly, the British agent was often berated by his own superiors for meddling in Mysore politics..

Finally, there were the people, especially a strong peasantry from what we now call the Lingayat community, with a history of rebellion against the Wadiyars. By the late 1820s, Krishnaraja had fallen out with the Marathi Brahmins, who in turn encouraged revolt in some districts..

A general economic depression had already agitated the peasants, and rebellion broke out in 1830. The British--misled into thinking that tribute would not be paid (even though the rajah had given it in advance to their agent), and blaming him for misgovernment--took over..

For 50 years the Wadiyars were out of power, and Krishnaraja waged a long battle for restoration. Even though the governor general who deposed him later conceded that the action had been unfair, others within the British system refused to return what was taken..

All kinds of fallacious arguments were aired but at the end of a fascinating legal process, on the eve of his death Krishnaraja's claims were admitted. As an aide wrote in triumph, 'Truth is always truth, on the banks of the Ganges, as well as on the Thames.'

But what is key is that the term 'misgovernment' under the Raj was not as simple as it seemed: it could have complex backstories, often linked to shifting balances of power & very local political interests.

Rulers thus managed not only pressures from above that the colonial power exerted, but also had to negotiate with their subjects. And powerful groups of subjects could also manipulate the British to pressure the maharajah and get what they wanted.

Basically a lot of cynical politics, then as today :)

(Again do excuse simplification. In the book the Mysore chapter is over 40 pages with 247 footnotes. Much more to chew on there.)

amazon.in/FALSE-ALLIES-I…

(Again do excuse simplification. In the book the Mysore chapter is over 40 pages with 247 footnotes. Much more to chew on there.)

amazon.in/FALSE-ALLIES-I…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh