"In assessing an individual’s risk of dying, age appears still as important—and maybe even more important—than vaccination status." Even in the age of vaccines and breakthroughs, age is a dominant, overlooked shaper of the pandemic. A long thread (1/x). nymag.com/intelligencer/…

In mid-September, King County, Washington released an eye-popping slide about vaccine efficacy: Vaccines had reduced the risk of infection from sevenfold and the risk of hospitalization and death 41-fold and 42-fold, respectively. pbs.twimg.com/media/E_Z_wfqV…

These ratios, though bigger than those found in other studies released in recent weeks, are nevertheless in line with an obvious emerging consensus in the data: Vaccines do clearly reduce transmission and dramatically reduce hospitalizations and deaths.

A recent CDC study of Los Angeles found a 29-fold reduction in hospitalization from vaccines early this summer, for instance, and another quasi-national study suggested an average 11-fold reduction in mortality risk overall. cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/7…

But in small type, King County included some other data too: Fully 25% of deaths were among vaccinated people. How can this be? If the vaccines are so effective they reduce mortality 42 times over, how could the vaccinated account for such a large proportion of the deaths?

The answer is actually quite simple: the overwhelming age skew of the disease, which—in the time of vaccines, breakthrough cases, and Delta—we are still hugely underestimating and which is governing the post-vaccine pandemic landscape as clearly as it did the pre-vaccine one.

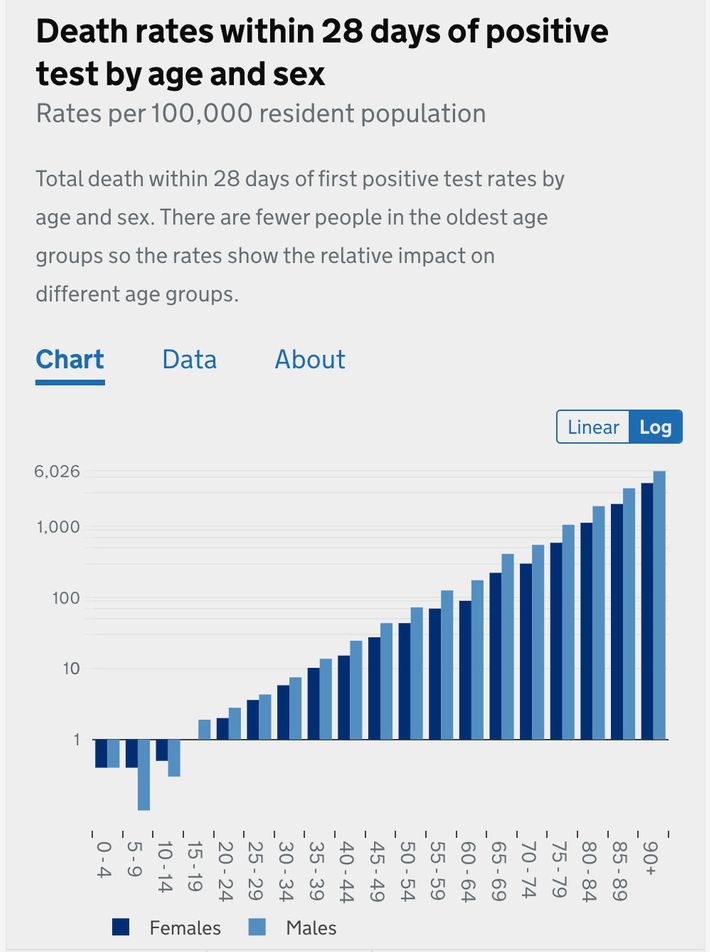

Most people know the pandemic has hit the elderly hardest — that is the meaning of the age skew, that the disease grows much more severe the older you are. But if they have seen a chart illustrating this, it probably looks like this gentle upward slope, from the NHS.

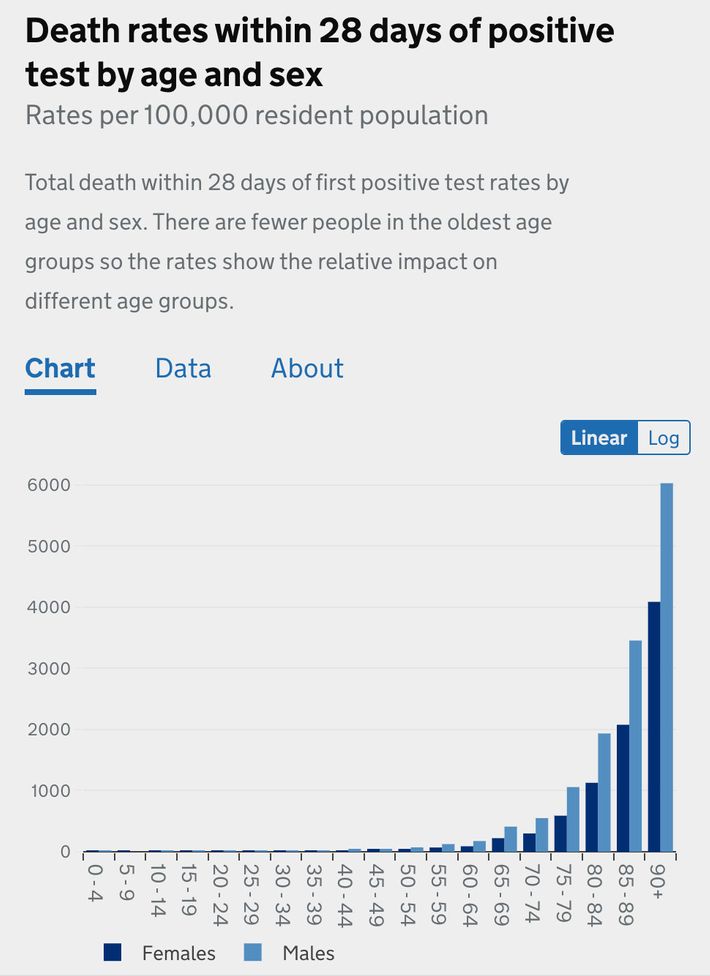

That is a logarithmic chart, which means that the y-axis scales exponentially. A chart of the same British information presented linearly (the graphing format you remember from elementary school) looks like this:

Viewed this way, the deaths from those under the age of 50 are more or less invisible.

To scale the graph to make them visible—and show that the risk slope from children to 50 year olds is about as dramatic as the slope from 50 year olds to 90 year olds—would require zooming in so much the bars representing elderly outcomes would tower above the top of your screen.

After 18 months of public-health guidance promoting universal vigilance, I think hardly any American has a clear view of just how dramatic these differentials are.

All else being equal, an unvaccinated 66-year old is about 30 times more likely to die, given a confirmed case, than an unvaccinated 36-year-old, and someone over 85 is over 10,000 times more at risk of dying than a child under 10.

And for all its transformative, liberating power, vaccination has not broken the basic age skew of the disease or offered anyone an exit ramp from it. Instead, in two profound ways, vaccination has confirmed the age skew...

First, by producing severe breakthrough cases concentrated overwhelmingly in the elderly and, second, by reducing the risk faced by individuals by an astonishing degree that is nevertheless smaller than the still more striking effect of age.

Although vaccines do substantially reduce the risk of infection, too, breakthrough cases are not terribly uncommon, accounting for perhaps as many as one-quarter of all new infections these days, as the CDC estimated in Los Angeles.

But they are overwhelmingly mild, and in the rare cases when they do grow severe, they tend to be among the old and very old. According to the CDC, 70 percent of breakthrough cases resulting in hospitalizations and 87 percent of those resulting in death were in patients over 65.

The median age of breakthrough deaths in England was 84; in King County, it was 79.

The second confirmation follows from the first. That 11-fold reduction of risk? Enormous, of course, but, as an average, represents only the equivalent of the difference between an unvaccinated 86-year-old man and a 61-year-old one, all else being equal.

According to an analysis of British data by the Financial Times, a vaccinated 80-year-old has about the same mortality risk as an unvaccinated 50-year-old, and an unvaccinated 30-year-old has a lower risk than a vaccinated 45-year-old. ft.com/content/0f11b2…

Even a 42-fold reduction, as was found in King County, would only be the rough equivalent of the difference between an unvaccinated 85-year-old and an unvaccinated 50-year-old— the sort of person who was very worried last year before the arrival of vaccines.

On the other end of the age spectrum, the same skew is more comforting. Recent data from the U.K. illustrate the phenomenon neatly: unvaccinated children are safer from COVID-19 death than vaccinated adults of any age.

https://twitter.com/apsmunro/status/1435964926464462851

According to that data, an unvaccinated 10-year-old, who may look like the very picture of COVID vulnerability heading into the school year, faces a lower mortality risk than a vaccinated 25-year-old, whom we might today regard as close to safe as can be.

In England, the incidence of hospitalization among unvaccinated kids was lower than that of those vaccinated aged 18-29, and in recent weeks, the hospitalization rate among kids ages 5 to 14 has been only about one per 100,000.

https://twitter.com/PaulMainwood/status/1436073744590639105

Over the course of the entire pandemic, which has killed more than 135,000 Brits, just one boy and seven girls between the ages of 5 and 9 have died; between the ages of 10 and 14, nine girls and five boys have died.

These are all tragedies — and each means many more years of life lost than with a death among the elderly — but they are nevertheless relatively few in number.

As schools reopened on the backslope of the U.K.’s Delta surge, there were about seven times as many British kids under age 5 hospitalized with the respiratory disease RSV as there were with COVID.

https://twitter.com/apsmunro/status/1430556935313666059

This is not to say that unvaccinated children face absolutely no risk from COVID, given that many millions of Americans under the age of 18 have gotten sick, and almost 500 have died, over the course of the pandemic.

It’s just that the risk those 73 million minors do face is—relative to the risks faced by their parents and grandparents—very, very small. (As I wrote a few months ago, though a better first line would have been “The kids are safe, relatively speaking”). nymag.com/intelligencer/…

But it is strange and perhaps unfortunate that in the ongoing, often ugly debate about vaccines, almost invariably the discussions describe two groups, the vaccinated and unvaccinated, as though they occupy two uniform and entirely different spheres of risk.

Because while the vaccine culture wars are indeed largely binary, and the future of the pandemic in the U.S. largely a matter of how many unvaccinated will get vaccinated...

...when we discuss individual risk, it simply doesn’t makes sense to talk about vaccinated 15-year-olds and 95-year-olds in the same breath and unvaccinated 15-year-olds and unvaccinated 95-year-olds in a different breath.

In fact, it distorts the picture of the pandemic as a whole when we regard risk as neatly divided by vaccination status. That’s because a vaccinated 95-year-old is still probably over a thousand times more at risk of death, all else being equal, than an unvaccinated 15-year-old.

Which means we probably shouldn’t be giving those two groups the same advice about masks or social distancing or boosters.

When I asked the CDC about the case fatality ratios implied by its study—which suggested vaccinated seniors were twice as likely to die, given a confirmed case, as unvaccinated people aged 50-64—the lead author suggested that it would be better to consider the incidence rate.

According to that measure, death among vaccinated seniors was two and a half times more common than death among unvaccinated people ages 18 to 49.

And so to believe that the vaccinated elderly are now perfectly safe, as can be tempting to all of us who are desperate for the unvaccinated to get with the program, is to raise an uncomfortable set of questions about the way we have processed risk by universalizing it.

If we want to believe, say, a vaccinated 75-year-old is safe, have we now simply normalized a higher level of individual risk than seemed moral to accept as recently as 12 months ago, given that they may not be any less in danger of dying than an unvaccinated 53-year-old?

If we are now debating what we can do, in schools especially, to protect unvaccinated children, who are much safer still, should we not be discussing at the same time what measures can be taken, beyond boosters, to protect the vaccinated elderly?

(Mask wearing offers differential benefits, too: according to the much-applauded study in Bangladesh, cloth masks of the kind typically worn by children offer very little protection, and the strongest effects of surgical masks were observed among the elderly.)

These are questions not just for individuals but also for communicators and public-health messaging.

Is it now more important to emphasize the protections offered by vaccines in order to encourage further uptake? Or to emphasize the enduring risks faced by the most vulnerable, who might take additional precautions as a result?

Because as long as the disease continues to circulate — in part because of frustratingly slow vaccine uptake — there will likely continue to be severe cases and deaths. That’s the brutal logic of the age skew and the vulnerability of the very old it describes.

Even universal vaccination among the elderly can’t eliminate those risks, only reduce them. In fact, in several of the recent studies of vaccine efficacy, the effect is notably smaller among the old.

(In King County, for instance, where vaccination was calculated to reduce the overall risk of death 42-fold, the effect among seniors was only eightfold.)

These studies’ findings obscure confounding variables — that is the nature of epidemiological analysis in real time — but taken together, they suggest that, as long as the disease continues to circulate, even the vaccinated elderly will continue to be vulnerable to some extent.

To what extent? “Post-vax COVID,” as @KatherineJWu called the “new disease” recently in the Atlantic, is much less lethal overall than the pre-vaxx or unvaxxed variety.

theatlantic.com/science/archiv…

theatlantic.com/science/archiv…

But making COVID only as lethal as pneumonia or the flu would still mean, as long as the disease sticks around, probably tens of thousands of American deaths annually.

Perhaps a young person can squint at that future and see something that still looks “normal.”

But they probably wouldn’t want to tell their grandparents to be blasé about catching pneumonia or the flu, even if they’ve had their annual shot — and might hope that public-health policy focused a bit more on those vulnerabilities rather than simply accepting them. (x/x)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh