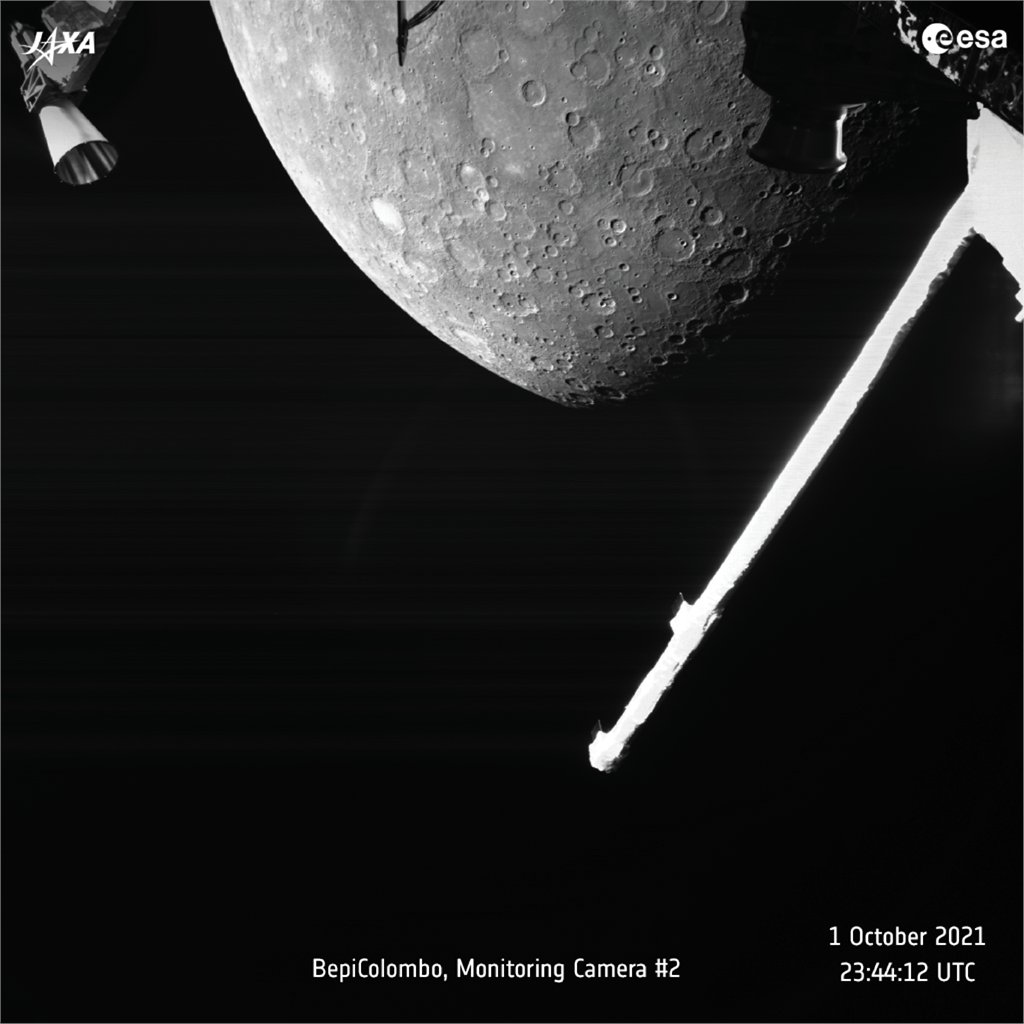

A flawless, radiant, #Mercuryflyby

After a flawless flyby of Mercury, @BepiColombo is starting to feel the heat.

After a flawless flyby of Mercury, @BepiColombo is starting to feel the heat.

At 01:34:41 CEST this morning, BepiColombo passed just 199 kilometres from the hot, rocky, innermost planet – the outcome of months of work to get the spacecraft into a precise trajectory for the first rendezvous with its target planet.

#MercuryFlyby

#MercuryFlyby

“It was flawless. Everything was perfect from the spacecraft point of view, and as expected, BepiColombo has really started to feel the heat,” explains Elsa Montagnon, Spacecraft #Operations Manager for the mission.

The spacecraft is currently plunging towards the centre of the Solar System. At 56 million kilometres away from the Sun, experiencing temperatures of about 110 degrees centigrade, this is a whole new environment for the spacecraft.

“BepiColombo was designed to fly in a pizza oven! Still, this was an important moment. Its one thing to prepare for the heat and another to watch the temperatures on our spacecraft rise. Its reassuring to see the different elements do their job to protect the mission" – Elsa

But its not just the design of the spacecraft that protects @BepiColombo from extreme heat, there’s also its precisely mapped trajectory.

These first images of Mercury don’t capture the planet’s ‘full face’, instead seeing just the section of lit up by sunlight – and these areas add to the temperature as they absorb and radiate the Sun’s heat.

“This is the second hottest planet in the Solar System: the mission is designed to orbit a hot marble, that is itself in orbit around a giant mass of fire and plasma. BepiColombo didn’t feel the full heat yet as we flew by Mercury over the cooler night side,” explains Elsa ...

“And now, as instruments are turned on for each #flyby, we’re finally getting data come in about our target planet. This mission and its instruments have been designed and built over decades, and this is the moment they’re getting first light of #Mercury, their new home.”

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh