Thread of threads on how to reduce the urban heat island effect. #1: Plant more street trees to reduce heat accumulation in streets and buildings.

https://twitter.com/wrathofgnon/status/1412312154141642752

#2: Allow where suitable natural climbing vines and vegetation to help shield buildings, keeping them cooler, reducing the need for air conditioning.

https://twitter.com/wrathofgnon/status/1046688365825863680

#3: All this street vegetation and the many trees will require a lot of water. To help, make all buildings water independent by encouraging rainwater harvesting. The goal should be to cover 100% of domestic use.

https://twitter.com/wrathofgnon/status/1363456214043160579

#4: Limit as far as possible urban sprawl by keeping cities dense. More sprawl means more paving and more buildings which leads to more heat buildup.

https://twitter.com/charlestonarchi/status/1239331587386494977

#5 A good tram system can do wonders in keeping sprawl and parking lots to a minimum, and the rail system can be so green as to be mistaken for a park. This helps a lot.

https://twitter.com/wrathofgnon/status/1110389063419228160

#6: Build streets that fit the climate. Narrower streets and taller buildings keeps the sun out in hot climates. Align streets to not catch sun during hottest hours. If prevailing winds: align streets to catch a breeze.

https://twitter.com/wrathofgnon/status/978157712604250112

#7: Use low-tech methods like awnings wide enough to cover the entire street during summers.

https://twitter.com/wrathofgnon/status/1346466000812736522

#8: Consider de-paving as many streets as possible, replace with grass or just dirt: both holds more water and accumulates far less heat than concrete or asphalt.

https://twitter.com/wrathofgnon/status/1418058646664081411

#9: Build cities for pedestrians and not cars. Watch the heat island effect more or less disappear completely.

https://twitter.com/wrathofgnon/status/1214409090341801984

#10: Consider transforming streets to canals. The canals will increase airflow, reduce heat accumulation and present a simple way of flushing out accumulated heat during daytime for cooler evenings.

https://twitter.com/wrathofgnon/status/1432930748420427780

#11: Stop cutting lawns.

https://twitter.com/wrathofgnon/status/1427675303615221767

#12: Keep track of the latest tools and methods in measuring and forecasting the effects of different interventions. This can save a lot of time and money in large mature cities especially.

https://twitter.com/wrathofgnon/status/1409348025256873992

#13: When you run out of interventions and still suffer from heat islands, consider espaliered urban orchards to make the best of it.

https://twitter.com/wrathofgnon/status/1412580833689432065

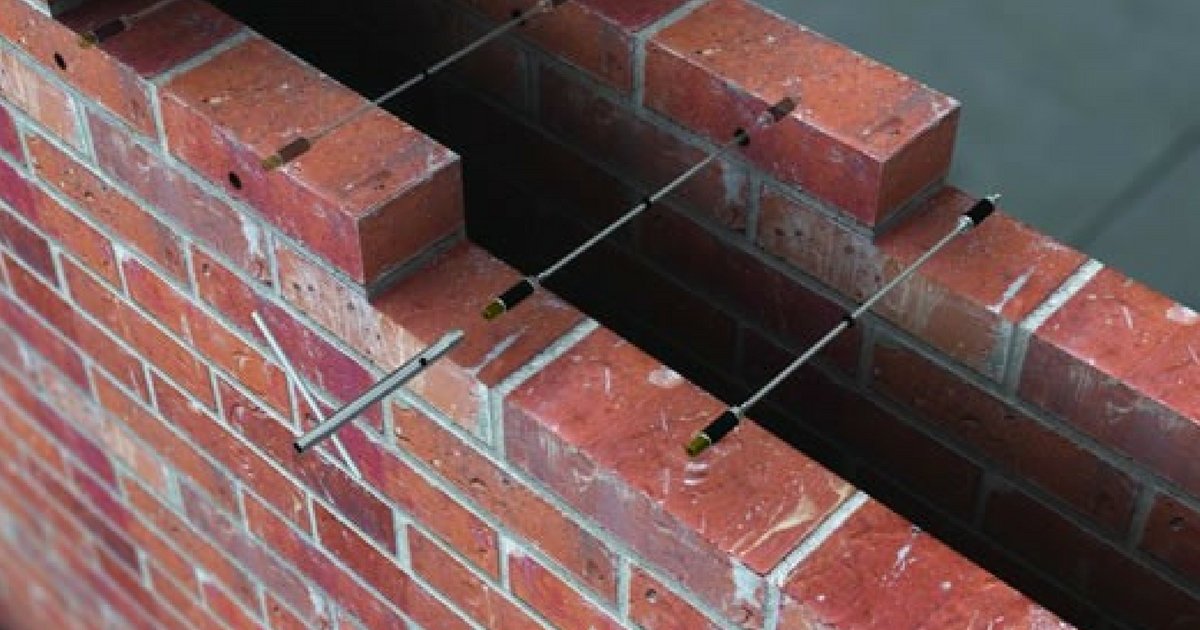

#14: Fine tune the airflow in existing buildings by modifying windows and interior transom windows to catch and steer winds. Natural ventilation is free, healthy, runs off-grid and will save lives in case of summer black outs. It is cheap to build too.

https://twitter.com/wrathofgnon/status/1341003151193751552

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh