St Giles’, Tadlow is a “well-lit by jewelled blue-grey windows; a characteristic floor, delicate strips of pink and yellow on the sanctuary walls, and a delicious font of pinkish grey on a white base”.

And it’s on the Heritage at Risk register.

#thread

And it’s on the Heritage at Risk register.

#thread

The quotation above is from Paul Thompson, William Butterfield’s biographer. You see, this is a medieval church “pleasantly placed, in a leafy position” that had a Butterfield restoration in the late 1800s.

2/

2/

If, like us, you keep an eye on the Church Commissioners’ consultation page on closed churches, you will see that there is a live consultation which seeks to put this Grade II* Cambridgeshire church into our care.

3/

3/

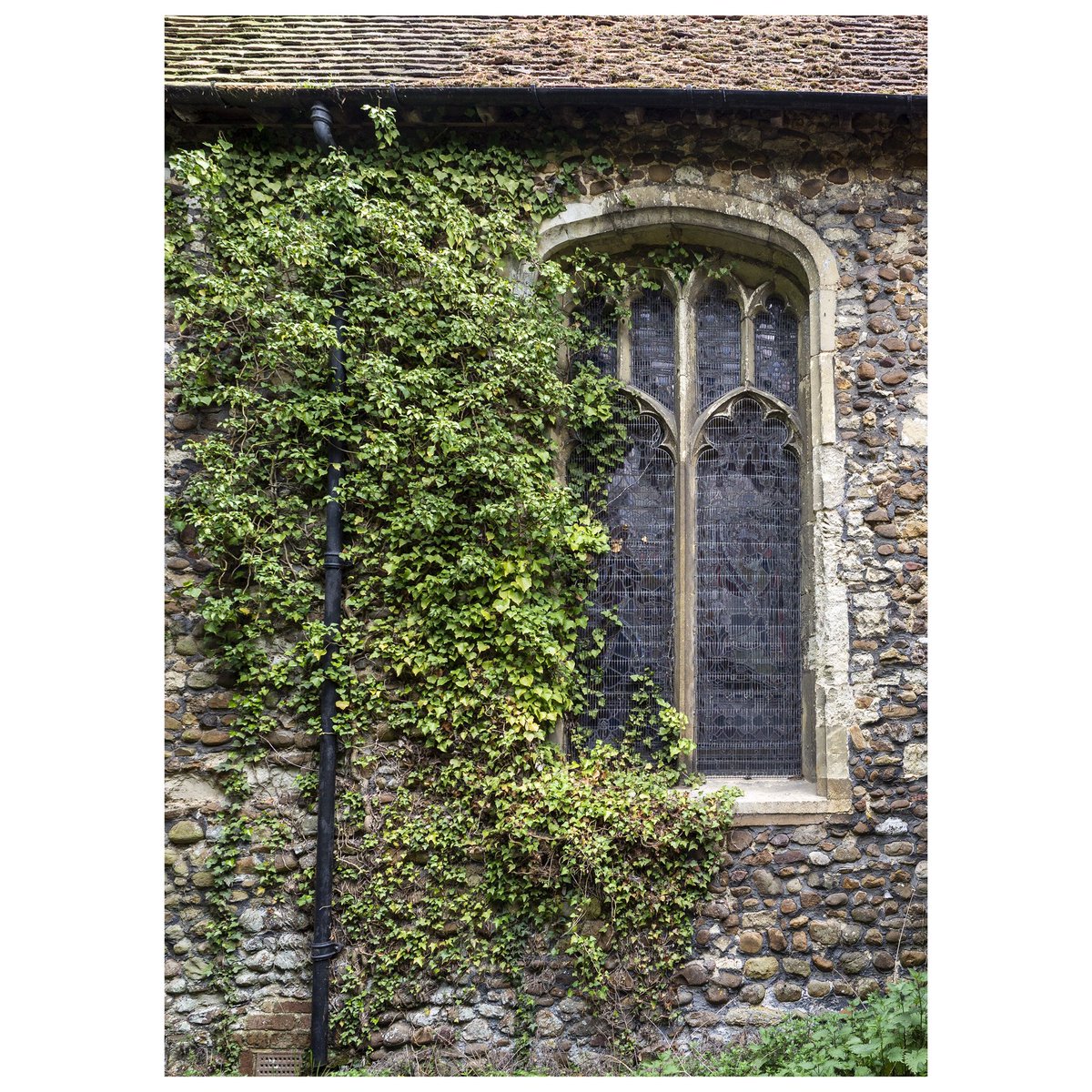

St Giles’ has its origins in the 13th century with walls and windows built from fieldstones and dressed but irregular blocks of Clunch.

The chalky tower was added in 1472.

4/

The chalky tower was added in 1472.

4/

It appears that the chancel was reduced in length some time before 1748 and appears to retain that footprint. Inside, the much-decayed floor slab with the ghost of an effigy just inside the south door is to Margaret Brogriffe of 1493.

5/

5/

But really, the inside is all about Butterfield. He spent the best part of 20 years (1855-1874) restoring this church. We are yet to learn what condition it was in when he began this restoration campaign.

6/

6/

As well as improving the internal environment of old churches, the aim of the Victorian High Movement was to reclaim the architectural nirvana of the 14th century – to return to this high point of religious expression in architecture. Colour was a hugely important part of this.

In most of Butterfield’s churches colour is confined to the sanctuary, floor, and font, and often only the east window has stained glass. The east window is by Butterfield’s favourite stained-glass artist, Alexander Gibbs.

Medieval fragments survive in some nave lights.

8/

Medieval fragments survive in some nave lights.

8/

The church comes with a mega list of repairs. It’s suffering severe structural movement, needs new roofs, drains, stone stitches, glazing repairs…

All going well, this church will be in our care next month. We can’t wait to start mending it, and welcoming people back.

9/

All going well, this church will be in our care next month. We can’t wait to start mending it, and welcoming people back.

9/

Huge thanks to @badger_beard for all of these great photos, and for being a friend to St Giles' over the past few years.

Commissioners' consultation: churchofengland.org/resources/pari…

10/10

Commissioners' consultation: churchofengland.org/resources/pari…

10/10

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh