On Jopadhola activism. Throughout the late 1950s, organisers articulated their frustrations about the state's economic demands & religious influences in Bunyole, Kisoko, & Tororo. On the one hand, communities were frustrated that the government & some writers in Buganda 1/7

insisted on accruing revenues from the region's cement production. On 20 February 1956, for instance, writers in Dobozi suggested that 'the Buganda Government should share in the revenue derived from Tororo cement [...] 2/7

b/c "it was through the generosity of the Baganda that the British ever went to those parts—in fact they were assigned to them by the Baganda."' On the other hand, writers in Padhola published an editorial in Uganda Empya on 7 June 1956, wondering 'whether the Protectorate 3/7

Government has taken any measures to stop that action [to separate religion from politics] as it is likely to hinder the development of Uganda.' Frustrations in eastern Uganda culminated in a series of protests and editorials in Uganda Argus in late 1962. 4/7

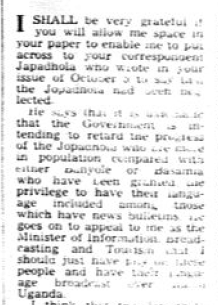

The Adhola Association organised in Aug. '62 to advocate for political-linguistic rights & representation. By 5 Oct., they issued an editorial, labelled "Jopadhola 'neglected'". The AA was especially concerned to see the government refusing to use Dhopadhola. 5/7

Adoko A. Nekyon (UPC, Lango SE) was Uganda's Minister of Information, Broadcasting and Tourism at the time. He responded by arguing that AA was simply upset that bulletins were also being issued in Lunyole, Lusaamia, and Lugwere. 6/7

Throughout the 1960s, the Adhola Association advocated for language and economic empowerment for communities throughout eastern Uganda. As the UPC moved increasingly to centralize resources throughout the late 1960s, their cause was met with increasing frustration. 7/7

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh