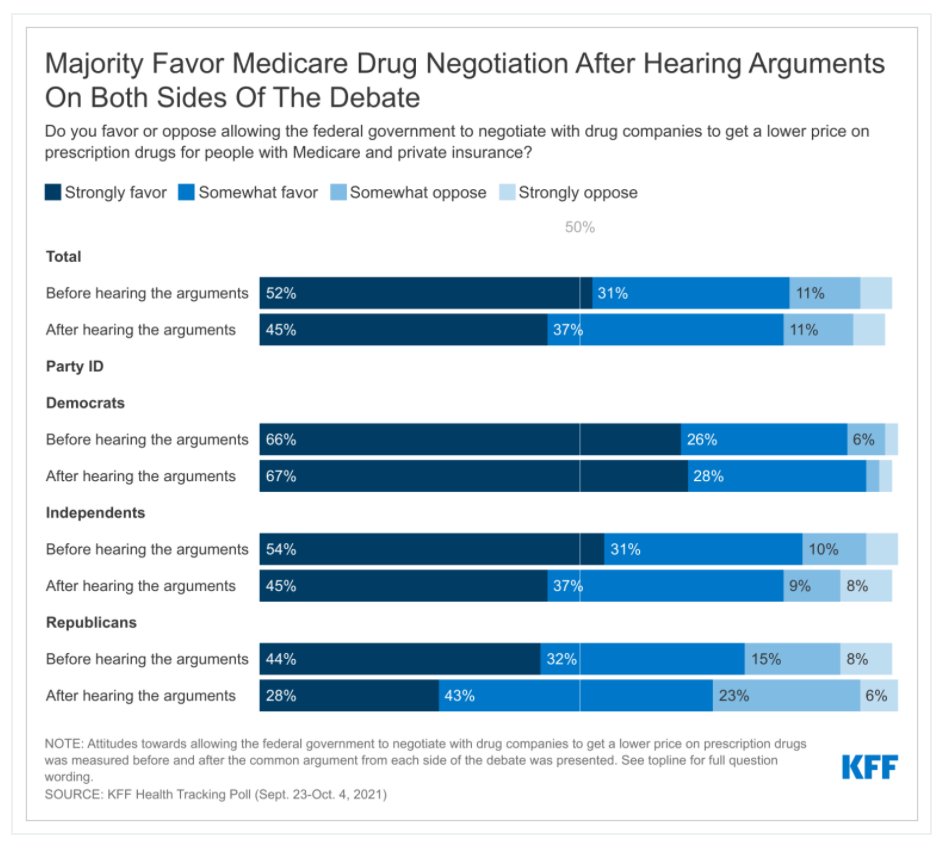

New: 83% of the public supports having the federal government negotiate drug prices, even after hearing arguments for and against the idea.

We didn't poll on baseball, motherhood, and apple pie, but I'm not sure they would score much higher.

kff.org/health-costs/p…

We didn't poll on baseball, motherhood, and apple pie, but I'm not sure they would score much higher.

kff.org/health-costs/p…

A big reason why the public overwhelmingly supports government negotiation of drug prices is that they don't buy the drug industry's arguments against it.

93% of people believe drug companies would still make enough to invest in research, even if prices in the U.S. were lower.

93% of people believe drug companies would still make enough to invest in research, even if prices in the U.S. were lower.

So much of the debate over the Build Back Better package has been on new spending and the overall price tag.

The provision that could prove to be among the most popular -- negotiation of drug prices -- saves money for both the government and patients.

The provision that could prove to be among the most popular -- negotiation of drug prices -- saves money for both the government and patients.

As with any complex piece of legislation, government negotiation of drug prices would pose trade-offs.

Lower prices could mean fewer new drugs come to market. It's not clear which drugs those would be.

It could also mean better access for patients with more affordable costs.

Lower prices could mean fewer new drugs come to market. It's not clear which drugs those would be.

It could also mean better access for patients with more affordable costs.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh