Origin of The Kurds

Much more is known of the Hurrians. They spoke a language of the Northeast Caucasian family of languages (or Alarodian), kin to modern Chechen and Lezgian. The Hurrians spread far and wide, dominating much territory outside their Zagros-Taurus mountain base.

Much more is known of the Hurrians. They spoke a language of the Northeast Caucasian family of languages (or Alarodian), kin to modern Chechen and Lezgian. The Hurrians spread far and wide, dominating much territory outside their Zagros-Taurus mountain base.

Their settlement of Anatolia was complete-all the way to the Aegean coasts. Like their Kurdish descendents, they however did not expand too far from the mountains.

Their intrusions into the neighboring plains of Mesopotamia and the Iranian Pteau, therefore, were primarily military annexations with little population settlement.

Their economy was surprisingly integrated and focused, along with their political bonds, mainly running parallel within the Zagros- Taurus mountains, rather than radiating out to the lowlands, as was the case during the preceding (foreign) Ubaid cultural period.

The mountain-plain economic exchanges remained secondary in importance, judging by the archaeological remains of goods and their origin.

The Hurrians-whose name survives now most prominently in the dialect and district of Hawraman/Awraman in Kurdistan- divided into many clans and subgroups, who set up city-states, kingdoms and empires known today after their respective clan names.

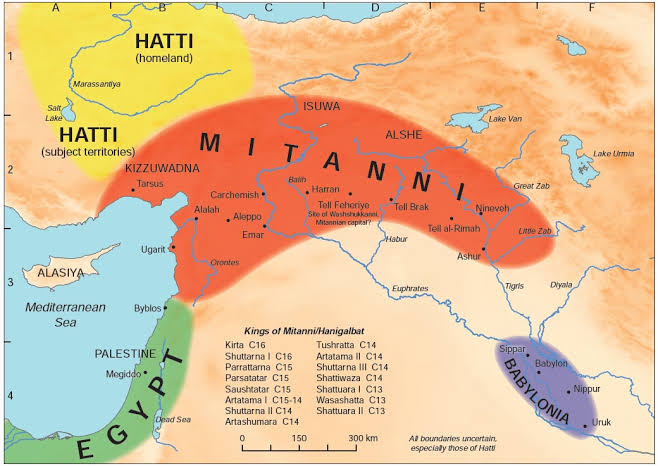

These included the Gutis, Kurti, Khadi, Mards, Mushku, Manna, Hatti, Mitanni, Urartu, and the Kassitis1es, to name just a few. All these were Hurrians, and together form the Hurrian phase of Kurdish history.

By about 4.000 years ago, the first vanguard of the Indo-European-speaking peoples were trickling into Kurdistan in limited numbers and settling there.

These formed the aristocracy of the Mitanni, Kassite, and Hittite kingdoms, while the common peoples there remained solidly Hurrian. By about 3,000 years ago, the trickle had turned into a flood, and Hurrian Kurdistan was fast becoming Indo-European Kurdistan.

Far from having been wiped out, the Hurrian legacy, despite its linguistic eclipse, remains the single most important element of the Kurdish culture until today.

It forms the substructure for every aspects of Kurdish existence, from their native religion to their art, their social organization, women’s status, and even the form of their militia warfare.

Medes, Scythians and Sagarthians are just the better-known clans of the Indo- European-speaking Aryans who settled in Kurdistan. By about 2,600 years ago, the Medes had already set up an empire that included all Kurdistan and vast territories far beyond.

By the advent of the classical era in 300 BC. Kurds were already experiencing massive population movements that resulted in settlement and domination of many neighboring regions. Important Kurdish polities of this time were all by-products of these movements.

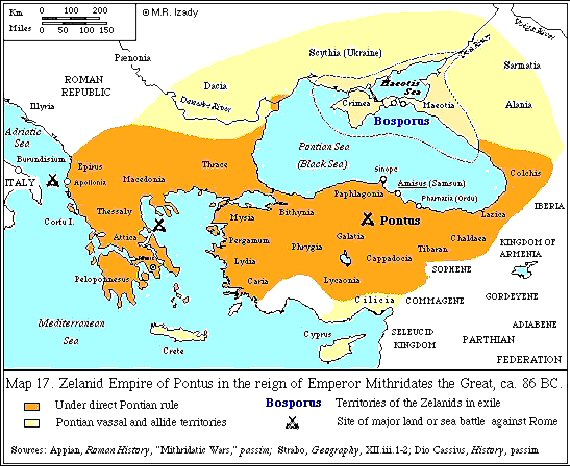

The Zelan Kurdish clan of Commagene (Adyaman area), for example, spread to establish in addition to the Zelanid dynasty of Commagene, the Zelanid kingdom of Cappadocia and the Zelanid empire of Pontus-all in Anatolia.

These became Roman vassals by the end of the Ist century BC. In the east the Kurdish kingdoms of Gordyene, Cortea, Media, Kirm, and Adiabene had, by the 1st century BC, become confederate members of the Parthian Federation.

While all larger Kurdish Kingdoms of the west gradually lost their existence to the Romans, in the east they survived into the 3rd century AD and the advent of the Sasanian empire.

The last major Kurdish dynasty, the Kayosids, fell in AD 380. Smaller Kurdish principalities (called the Kohyar, “mountain administrators”) however, preserved their autonomous existence into the 7th century and the coming of Islam.

Several socio-economic revolutions in the garb of religious movements emerged in Kurdistan at this time, many due to the exploitation by central governments, some due to natural disasters.

These continued as underground movement into the Islamic era, bursting forth periodically to demand social reforms. The Mazdakite and Khurramite movements are best-known among these.

The eclipse of the Sasanian and Byzantine power by the Muslim caliphate, and its own subsequent weakening, permitted the Kurdish principalities and “mountain administrators” to set up new, independent states.

The Shaddadids of the Caucasus and Armenia, the Rawadids/Rawandids of Azerbaijan, the Marwandis of eastern Anatolia; the Hasanwayhids, Fadhilwayhids, and Ayyarids of the central Zagros and the Shabankara of Fars and Kirman are some of the medieval Kurdish dynasties.

The Ayyubids stand out from these by the vastness of their domain. From their capital at Cairo they ruled territories of eastern Libya, Egypt, Yemen, western Arabia, Syria, the Holy Lands, Armenia and much of Kurdistan.

For one last time a large Kurdish kingdom–the Zand, was born in 1750. Like the medieval Ayyubids, however, the Zands set up their capital and kingdom outside Kurdistan, and pursued no policies aimed at unification of the Kurdish nation.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh