The story of Lot and his people in the Quran recurs strikingly often throughout the Quran (Q11:77-83; Q15:51-77; Q26:160-75; Q27:54; Q37:133-8; Q51:24-37; Q54:33-9; Q80:33-42), and finds clear parallels with the story as told in Gen. 19.

A thread on a specific reading variant. 🧵

A thread on a specific reading variant. 🧵

It's been noted that a pivotal moment in the original story about Lot's wife is told quite differently in the Quran than how it is in the Genesis. In Genesis, as Lot and his family leave Sodom & Gomorrah, his wife looks back and turns into a pillar of salt.

In the Quran, the pillar of salt is missing entirely, and generally it's not the wife's looking back that causes her perdition. Instead she is said to be left behind, or even decreed to be left behind, e.g. Q15:60; Q27:57; Q37:135. But Q11:81 forms a confounding factor.

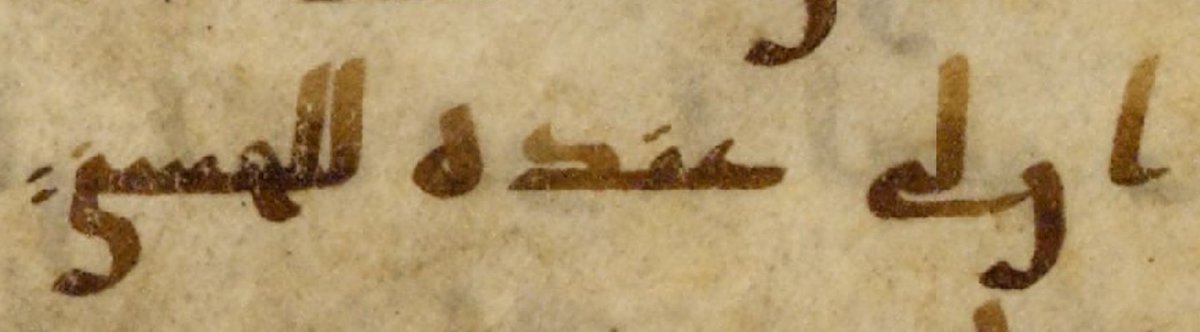

Here 2 Angels come to warn Lot, and command him to leave with his family, and not turn around. After that a phrase follows: إلا امرأتك, which can be read in two different ways: ʾillā mraʾataka and ʾillā mraʾatuka. Both mean "except your wife", but what is being excepted differs.

The section consists of three phrases:

fa-ʾasri/fa-sri bi-ʾahlika bi-qiṭʿin mina l-layli "So travel with your family during a portion of the night"

wa-lā yaltafit minkum(ū) ʾaḥadun "and let among you not one turn around"

ʾillā mraʾataka/mraʾatuka "except your wife".

fa-ʾasri/fa-sri bi-ʾahlika bi-qiṭʿin mina l-layli "So travel with your family during a portion of the night"

wa-lā yaltafit minkum(ū) ʾaḥadun "and let among you not one turn around"

ʾillā mraʾataka/mraʾatuka "except your wife".

ʾillā "except" in positive sentences, is followed by the accusative, e.g. fa-saǧadū ʾillā ʾiblīsa "they prostrated, except for ʾIblīs".

But when excepting a negative sentence, it shows up in the nominative, as in lā ʾilāha ʾillā ḷḷāhu "there is no god but God".

But when excepting a negative sentence, it shows up in the nominative, as in lā ʾilāha ʾillā ḷḷāhu "there is no god but God".

So with: ʾillā mraʾataka, it excepts the positive phrase "so travel with your family, except your wife!". This is the majority reading.

ʾAbū ʿAmr and Ibn Kaṯīr read: ʾillā mraʾatuka, excepting the negative phrase: "And not one of you shall turn around, except your wife!"

ʾAbū ʿAmr and Ibn Kaṯīr read: ʾillā mraʾatuka, excepting the negative phrase: "And not one of you shall turn around, except your wife!"

Clearly these two readings are difficult to unify. Either the wife did not travel along, and stayed behind, or she went along and looked back (and turned into a pillar of salt?). Some exegetes on this verse:

1. Ibn Ḫālawayh (d. 381)

2. al-Ṭabarī (d. 310)

3. al-Farrāʾ (d. 207)

1. Ibn Ḫālawayh (d. 381)

2. al-Ṭabarī (d. 310)

3. al-Farrāʾ (d. 207)

The biblical parallel is tempting and Arberry indeed translates it (accidentally?) in the minority reading. This is taken up by Nora Schmid in her excellent paper in this verse (though she cites the majority reading, to which the translation does not match).

But the other verses in the Quran, seem to suggest that Lot's wife did not come along and look back. No, they seem to suggest she never came along in the first place. Moreover, the episode about turning into a pillar of salt is completely missing.

Moreover, the companion Ibn Masʿūd is reported by al-Farrāʾ and others to have lacked the phrase wa-lā yaltafit minkum(ū) ʾaḥadun "and let among you not one turn around" altogether, which makes the thing which is being excepted even clearer.

Al-Ṭabarī is clear in his opinion, after reporting readings that lacked this phrase: "This points to the correctness of the reading with the accusative" (i.e. the wife being left behind). Thus (softly) rejecting the now canonical reading with the nominative.

So what do we make of Ibn Kaṯīr and his student ʾAbū ʿAmr's reading? Were they familiar with the biblical story, and did it tempt them to read it with the nominative? It is a real shame that academia seems wholly unaware of this reading and this grammatical subtlety.

As a result works that are explicitly concerned with this verse, and even explicitly with the biblical parallels miss commenting on this variant entirely (no mention in Le Coran des Historiens either for example, ).

Western commentaries on the Quranic text really ought to integrate the Quranic reading traditions more. #hafsonormativity is enough of a problem, but when commenting on the earliest strata of the Quran, you really can't rely on only one authority who became popular only very late

If you enjoyed this thread and want me to do more of it, please consider buying me a coffee.

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

(for the pedants among us: the case after ʾillā in negated sentences is technically not always nominative. It simply follows the case of the word it is excepting)

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh