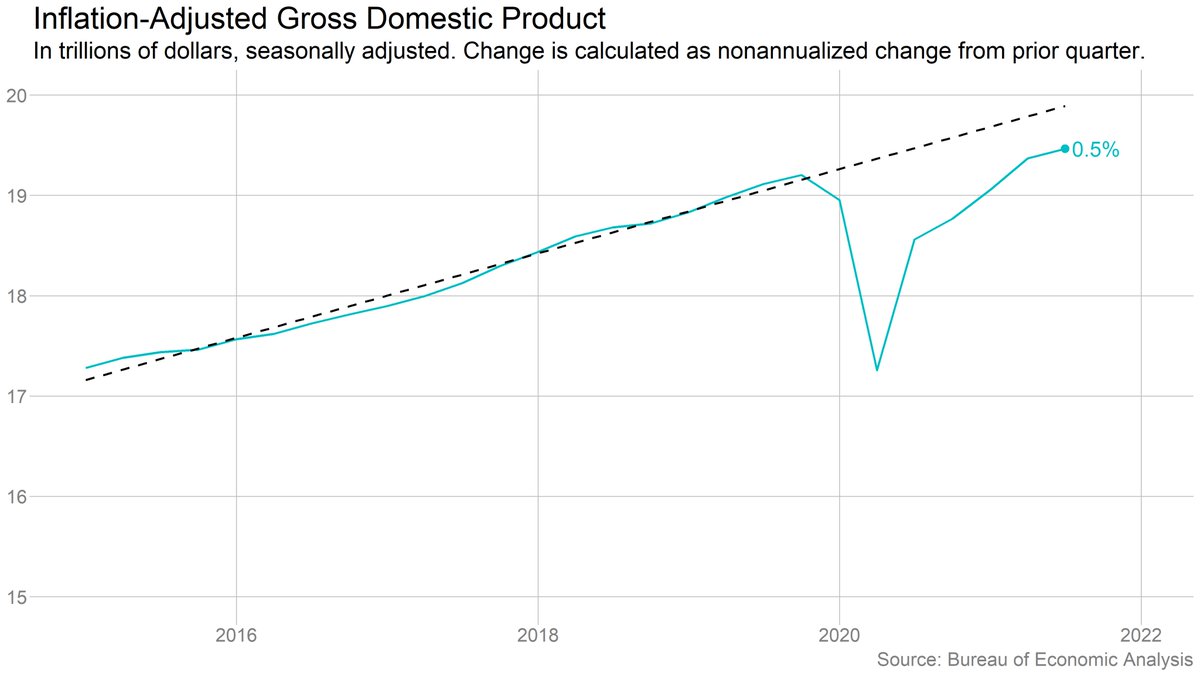

Economic output grew 0.5% in the third quarter (2% annualized). That's a sharp slowdown from the 1.6% (6.7% annualized) in Q2, as supply chain woes and the rise of the Delta variant constrained growth.

nytimes.com/live/2021/10/2…

nytimes.com/live/2021/10/2…

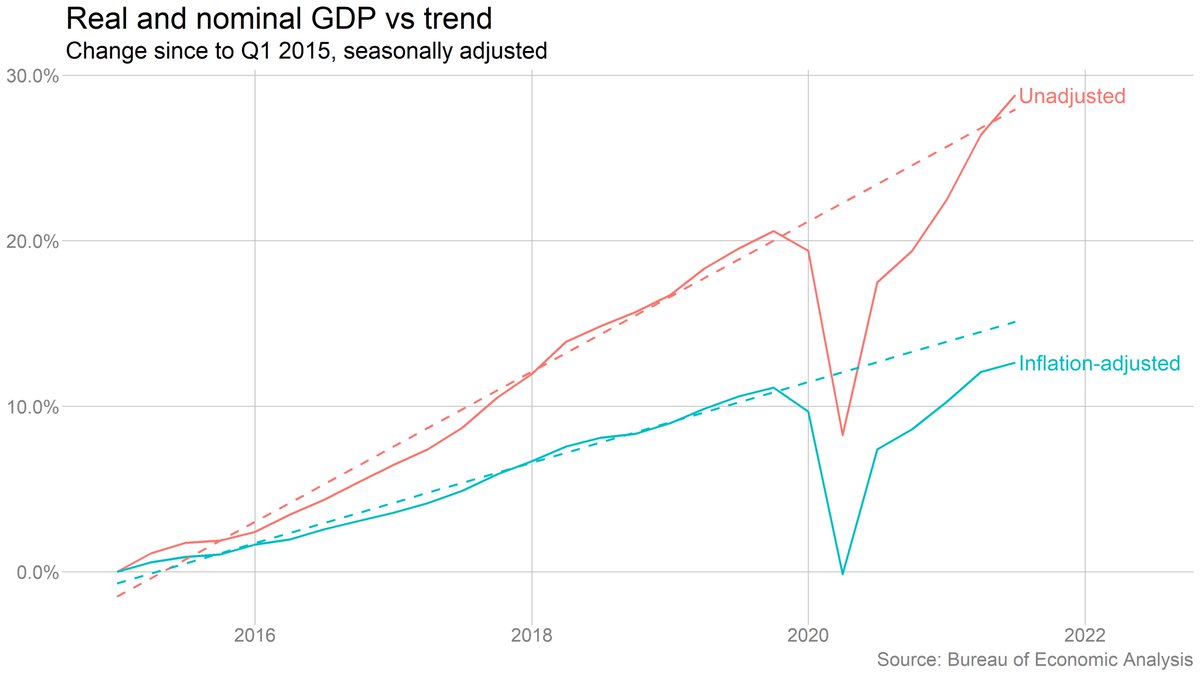

U.S. GDP surpassed its prepandemic level in the second quarter, but it's still well below the prepandemic trend.

But inflation is a big part of the story here. Nominal (non-inflation-adjusted) GDP is back on its prepandemic trend. But real (inflation-adjusted) GDP is below. Fits with the story of demand outstripping supply, so some of it ends up as higher prices, not more production.

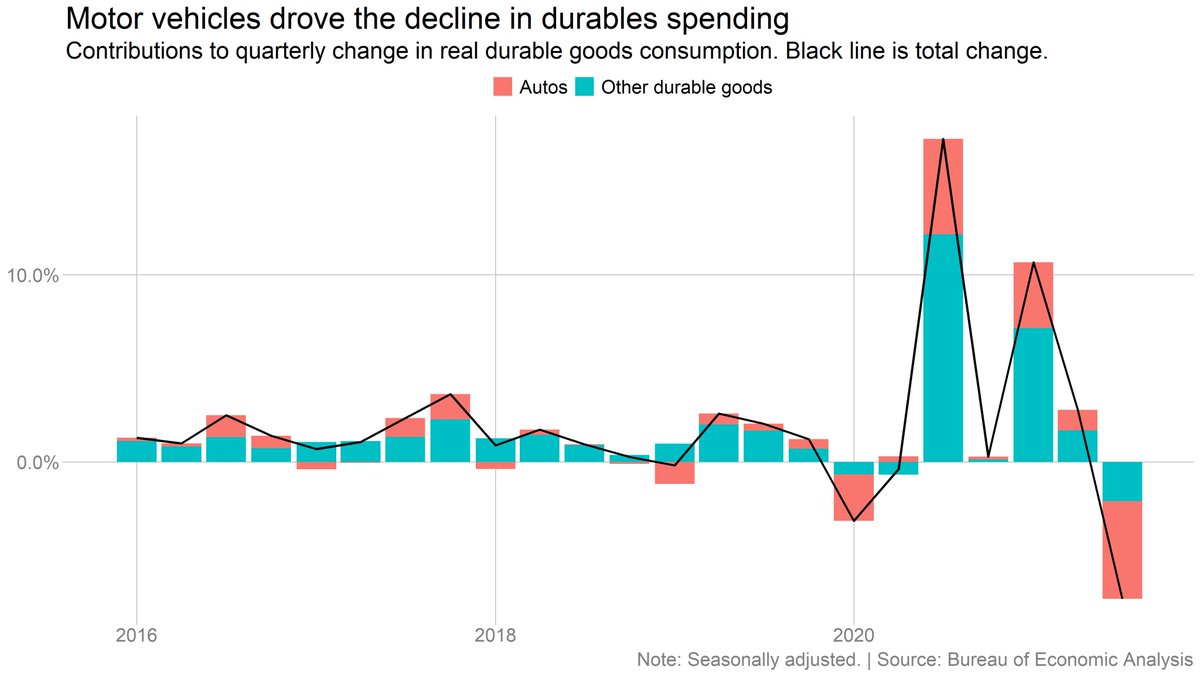

Supply chain snarls played a big role in the Q3 slowdown. Spending on durable goods fell 7%, with autos making up a huge part of the decline.

nytimes.com/live/2021/10/2…

nytimes.com/live/2021/10/2…

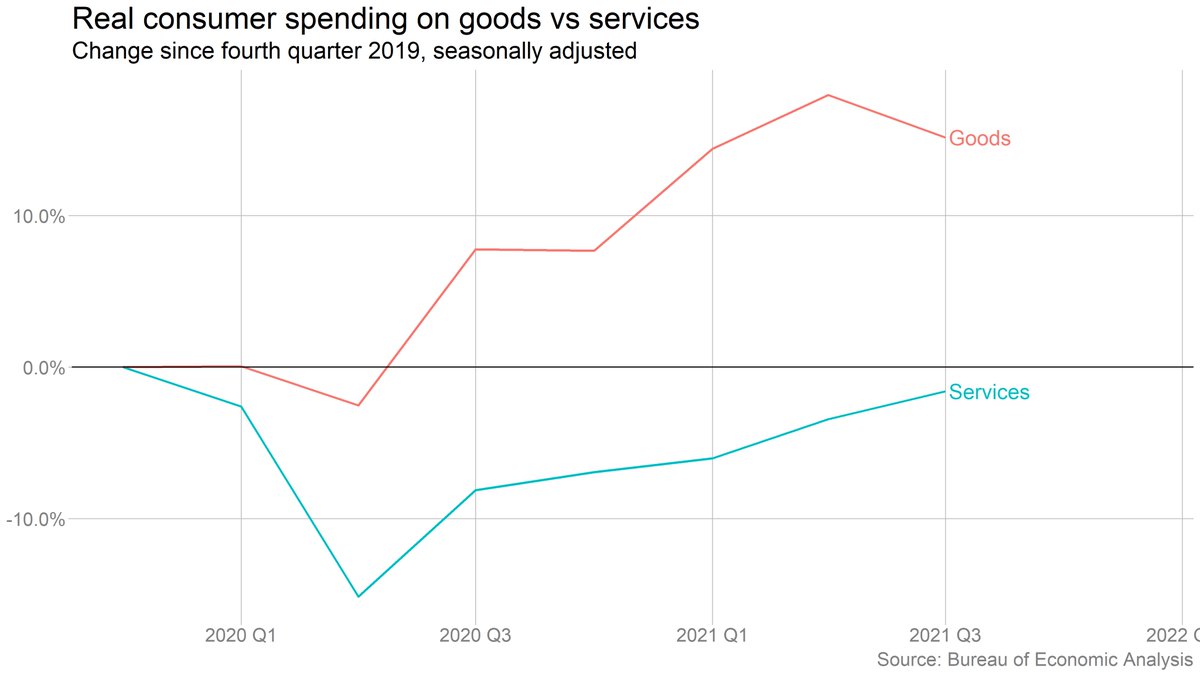

Services spending rose, but more slowly. Spending at hotels and restaurants had been helping to drive the rebound in services spending, but momentum slowed in Q3 because of Delta.

But the big picture is important here. Spending on goods is still way above its pre-Covid level and falling only gradually. Services spending is rising, but still below where it was before the pandemic. And all of that goods spending is contributing to the supply-chain issues.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh