1/ There's a well known anecdote from The Everything Store about Jeff Bezos visiting Harvard Business School in 1997. The students told Bezos "you really need to sell to Barnes and Noble and get out now"

Less well known: you can read the actual 1997 HBS case study from the class

Less well known: you can read the actual 1997 HBS case study from the class

2/ It's easy to laugh at predictions in retrospect - but with the information available at the time, would you have known better?

store.hbr.org/product/leader…

store.hbr.org/product/leader…

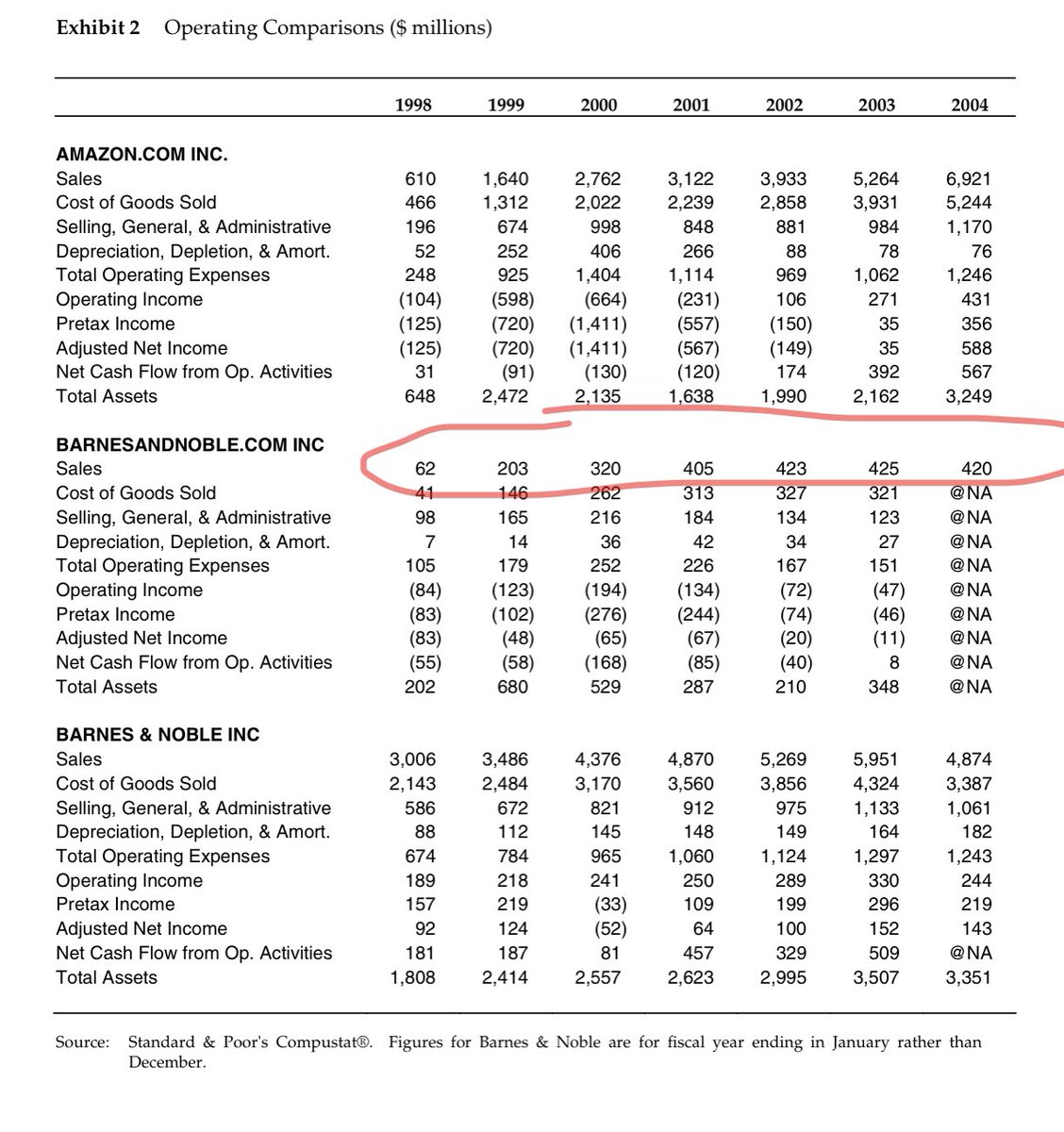

3/ In 1997, Amazon was 3 years old and generated $148M in sales, entirely in the book industry. Barnes and Noble was 26 years old and was 15x bigger, at $2.5B in sales

4/ In contrast to the vertically-integrated Amazon of today, the Amazon of 1997 held little inventory and relied on its wholesaler Ingram to ship 59% of its books

In other words: in 1997, Amazon was really just an outsourced website layer built atop an Ingram warehouse

In other words: in 1997, Amazon was really just an outsourced website layer built atop an Ingram warehouse

5/ To compete with Amazon, Barnes and Noble launched BarnesAndNoble.com in 1996 as an internal 50-person startup

Unlike Amazon, BarnesandNoble.com shipped books from their own warehouse from the get-go, resulting in *faster* delivery times than Amazon

Unlike Amazon, BarnesandNoble.com shipped books from their own warehouse from the get-go, resulting in *faster* delivery times than Amazon

6/ In other words: In 1997, Amazon was a money-losing niche vertical ecommerce player with no hard assets, facing entry from a much larger incumbent with a comparable (or arguably superior) value prop

7/ But everybody knows how this story ends! BarnesandNoble.com's revenues permanently flatline after the tech bubble at around $400M. Amazon kept growing, from $150M in 1997 to $2.8B in 2000 and $7B in 2004

Could anything in the HBS case have foreshadowed this?

Could anything in the HBS case have foreshadowed this?

8/ First hint: Barnesandnoble.com wasn't allowed to leverage the distribution of physical Barnes and Noble stores, because that would have subjected them to sales tax. In other words, B&N handicapped itself to compete on the same playing field as Amazon

9/ Second hint: Even in 1997, Jeff Bezos didn't stand still. Barnesandnoble.com's in-house warehouse was the catalyst for Amazon to pivot away from the asset-light model and vertically integrate into fulfillment and logistics

10/ What's the takeaway here? The Amazon of 1997 was not the Amazon of today. Frankly speaking, it was a much weaker, much less defensible business.

For early stage companies, you're not really betting on a business as it is. You're betting on a business as it *could* be.

For early stage companies, you're not really betting on a business as it is. You're betting on a business as it *could* be.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh