He evacuated troops near Dunkirk. He rescued survivors of ships torpedoed by the Nazis. While at sea, he slept standing up.

He rode a torpedo.

Now, Harry DeWolf is circumnavigating North America.

He rode a torpedo.

Now, Harry DeWolf is circumnavigating North America.

1940. Near Dunkirk, HMCS St. Laurent is rescuing soldiers when a German bomber appears.

The ship’s gunners are ready. They wait for the order. The bomber rakes the ship with bullets. Bombs land ten feet away.

DeWolf: Why the hell didn't you fire?

Gunnery Officer: Sorry, sir.

The ship’s gunners are ready. They wait for the order. The bomber rakes the ship with bullets. Bombs land ten feet away.

DeWolf: Why the hell didn't you fire?

Gunnery Officer: Sorry, sir.

July 1940. The SS Arandora Star leaves Liverpool bound for Canada carrying more than 1600 Italian and German prisoners of war. A German U-boat torpedos the ship.

In waters teeming with enemy submarines, DeWolf and the crew of HMCS St. Laurent rescue 857, including these sailors.

In waters teeming with enemy submarines, DeWolf and the crew of HMCS St. Laurent rescue 857, including these sailors.

A sailor is painting aboard HMCS St. Laurent when he lifts the firing handle of a torpedo to paint under it. Yes. The firing handle. To paint underneath it. It could happen to anyone.

The torpedo ping-pongs around the deck like a baby moose through Aunt Lucy's rhubarb patch.

The torpedo ping-pongs around the deck like a baby moose through Aunt Lucy's rhubarb patch.

"It was as slippery as a greased pig and we thought its propeller might cut our feet off. We rode and guided it over the rail and stuck one leg over the rail to hold it steady.”

They release the air cock to stop that baby moose of a torpedo.

They release the air cock to stop that baby moose of a torpedo.

The English Channel. April 1944.

Now commanding HMCS Haida, DeWolf is patrolling for German warships with HMCS Athabaskan. An explosion from Athabaskan shoots flames 50 feet into the air.

The ship is sinking. Survivors scramble to abandon ship.

Now commanding HMCS Haida, DeWolf is patrolling for German warships with HMCS Athabaskan. An explosion from Athabaskan shoots flames 50 feet into the air.

The ship is sinking. Survivors scramble to abandon ship.

DeWolf chases the enemy ships, driving one aground.

They return to rescue as many survivors as quickly as possible. The enemy is lurking and Haida is a sitting duck. Knowing his fate, Athabaskan’s Lieutenant-Commander John Stubbs, warns off DeWolf.

“Get away, Haida! Get clear!"

They return to rescue as many survivors as quickly as possible. The enemy is lurking and Haida is a sitting duck. Knowing his fate, Athabaskan’s Lieutenant-Commander John Stubbs, warns off DeWolf.

“Get away, Haida! Get clear!"

DeWolf and the crew of Haida save 42 sailors. Mona Rolls’ husband is not among them.

Back in Calais, Maine, she would soon receive word that he is lost at sea.

Able Seaman Raymond Burton Rolls was 21 years old.

Back in Calais, Maine, she would soon receive word that he is lost at sea.

Able Seaman Raymond Burton Rolls was 21 years old.

His crews called him “Hard-Over Harry.” Under his command, Haida sank more enemy ships than any other in the Canadian Navy.

But the deaths of those German sailors haunted him for the rest of his life.

He said that children grew up without their fathers “because of me.”

But the deaths of those German sailors haunted him for the rest of his life.

He said that children grew up without their fathers “because of me.”

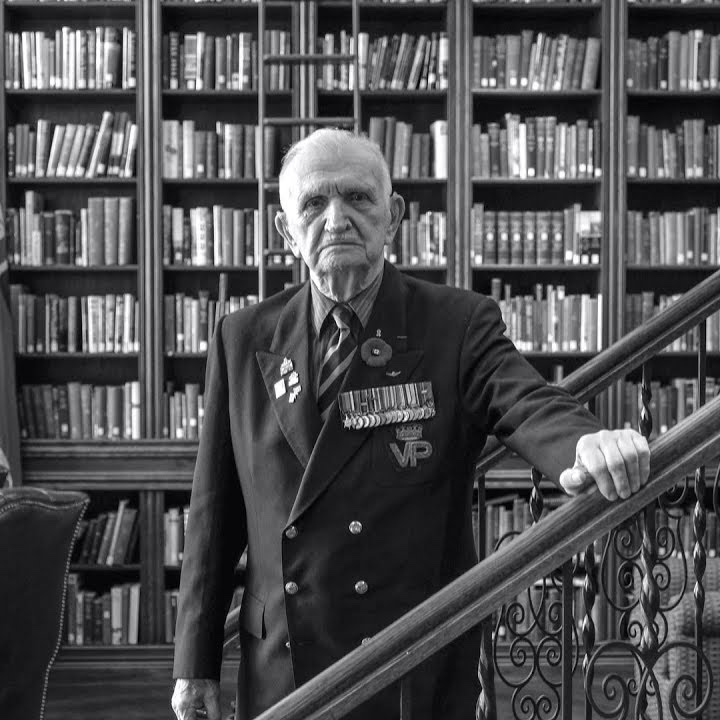

Distinguished Service Order. Distinguished Service Cross. Two Mentions in Dispatches. Officer of the U.S. Legion of Merit and the French Légion d'honneur.

His portrait is on the wall of the Canadian Embassy in Washington, DC.

Vice-Admiral Harry DeWolf died in 2000.

His portrait is on the wall of the Canadian Embassy in Washington, DC.

Vice-Admiral Harry DeWolf died in 2000.

So, no, Hard-Over Harry himself is not circumnavigating North America. But the newest ship in the Royal Canadian Navy, the ship that bears his name, is.

HMCS Harry DeWolf carries his spirit.

HMCS Harry DeWolf carries his spirit.

In August, the ship left Halifax, Nova Scotia, and headed for the Northwest Passage, passing the hand of Franklin still reaching for the Beaufort Sea.

Along the way, the crew worked with HMCS Goose Bay, Canadian Coast Guard ships, and some Coasties who were far from home.

Along the way, the crew worked with HMCS Goose Bay, Canadian Coast Guard ships, and some Coasties who were far from home.

@USCG @USCGNortheast The crew worked with the Canadian Rangers. When you’re in the North, you listen to them.

Always listen to the Canadian Rangers.

Always listen to the Canadian Rangers.

After transiting the Northwest Passage, HMCS Harry DeWolf is heading south.

The crew will support U.S.-led efforts to counter illicit drug trafficking in the Caribbean and eastern Pacific before returning to Halifax.

The crew will support U.S.-led efforts to counter illicit drug trafficking in the Caribbean and eastern Pacific before returning to Halifax.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh