The Lower text of the Sanaa Palimpest is exciting to researchers, because its lower text is a non-Uthmanic version of the Quran. When the wording differs between the Palimpsest and the Uthmanic text, how do we decode which one is more original? A thread on a variant at Q19:26 🧵

Q19:26 in the standard text reads ʾinnī naḏartu li-r-raḥmāni ṣawman fa-lan ʾukallima l-yawma ʾinsiyyan "I vowed a fast to the All-Merciful, so I will not speak to any human today".

In the Sanaa Palimpsest there is clearly another word between ṣawman and the following sentence

In the Sanaa Palimpsest there is clearly another word between ṣawman and the following sentence

The relevant portion of the lower text is exceptionally difficult to read, even in the UV photos, but just enough can be made out to be able to tell that there is another word.

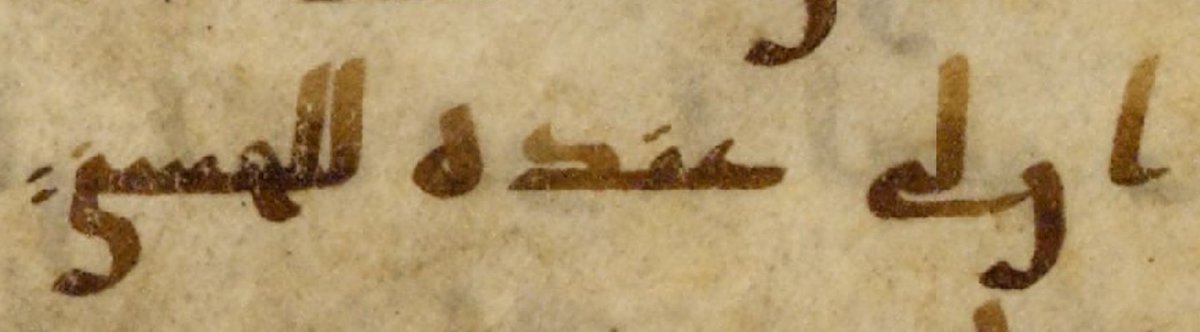

@MohsenGT managed to just make out the relevant traces in the their edition.

@MohsenGT managed to just make out the relevant traces in the their edition.

Here is me trying to produce a trace of what is visible there. As with the transcription in Sadeghi & Goudarzi, I indeed see a word with the shape وصمٮا, i.e. wa-ṣamtan "I vowed a fast AND A SILENCE to the All-Merciful, so I will not speak to any human today"

This is a well-known variant, reported as a recitation for ʾAnas b. Mālik by Ibn Ḫālawayh.

ʾAbū Ḥayyān also attributes it to Ibn Masʿūd's Muṣḥaf.

So this was clearly a variant present in the early Islam. So we may ask: which of these competing readings is more original?

ʾAbū Ḥayyān also attributes it to Ibn Masʿūd's Muṣḥaf.

So this was clearly a variant present in the early Islam. So we may ask: which of these competing readings is more original?

In his seminal "The Codex of a Companion of the Prophet and the Qurʾān of the Prophet", Sadeghi sets up several criteria to decided the direction of a variant, in the context of dictation, and the implication they have for directionality.

Let's go through them.

Let's go through them.

1. Changes of Minor Elements.

This is by far the most common difference between the Sanaa Palimpsest and the standard text. Interchanges of wa-, fa-, or the omission or inclusion of extremely common words such as Aḷḷāh.

With these it is hard to decide on the direction of change

This is by far the most common difference between the Sanaa Palimpsest and the standard text. Interchanges of wa-, fa-, or the omission or inclusion of extremely common words such as Aḷḷāh.

With these it is hard to decide on the direction of change

2. Omissions of Major Elements.

When someone is writing down a text from dictation, they are more likely to forget a word they heard rather than add a word they did not hear at all. Thus, barring other mechanisms, variation should go from more words to fewer words.

When someone is writing down a text from dictation, they are more likely to forget a word they heard rather than add a word they did not hear at all. Thus, barring other mechanisms, variation should go from more words to fewer words.

3. Auto-contamination.

Auto-contamination is one of the cases where a word may be added. The Quran is highly self-similar, so someone familiar with the text might add a word that is present in parallel verses elsewhere in the text, in a place it does not belong.

Auto-contamination is one of the cases where a word may be added. The Quran is highly self-similar, so someone familiar with the text might add a word that is present in parallel verses elsewhere in the text, in a place it does not belong.

Auto-contamination can happen either

a. Due to a parallel verse in a different location in the Quran.

b. Due to a not-quite parallel but nearby verse with similar wording.

a. Due to a parallel verse in a different location in the Quran.

b. Due to a not-quite parallel but nearby verse with similar wording.

4. Phonetic Conservation in Major Substitutions.

Sometimes one word may be replaced for another, but still be more or less the same in sound and wording. In such cases direction is difficult to decided, e.g.

Q5:41 Uthmanic wa-lahum fī l-ʾāḫirati ~ Sanaa wa-fī l-ʾāḫirati lahum.

Sometimes one word may be replaced for another, but still be more or less the same in sound and wording. In such cases direction is difficult to decided, e.g.

Q5:41 Uthmanic wa-lahum fī l-ʾāḫirati ~ Sanaa wa-fī l-ʾāḫirati lahum.

5. Common or Frequent Terms.

Sometimes a frequent term may be replaced with another frequent term in cases of misremembering. In these cases a direction of change is difficult to tell as well.

So what about the variant ṣawman wa-ṣamtan? Can we explain this as an addition?

Sometimes a frequent term may be replaced with another frequent term in cases of misremembering. In these cases a direction of change is difficult to tell as well.

So what about the variant ṣawman wa-ṣamtan? Can we explain this as an addition?

The only way that a word can be added 'accidentally' in dictation is due to auto-contamination (criterion 3). But that cannot explain the variant here.

The whole phrase is unique, ṣawman is a hapax legomenon ("read once"), the word ONLY occurs here.

The whole phrase is unique, ṣawman is a hapax legomenon ("read once"), the word ONLY occurs here.

The added word wa-ṣamtan, in fact, does not occur in the Uthmanic text at all. As such, we can safely exclude the possibility of auto-contamination, there is no place where a scribe could have gotten wa-ṣamtan from in the text of the Quran.

Therefore, the more likely explanation is that it is a case of Major Omission in the Uthmanic text. i.e. When the Quranic text was dictated, the dictation had the phrasing ʾinnī naḏartu li-r-raḥmāni ṣawman wa-ṣamtan. But the Uthmanic scribe failed to write down this word.

This is an example of what Sadeghi calls a "major plus" that cannot easily be explained as the result of issues of memory while writing down from dictation.

In other words: the Sanaa Palimpest seems to have the more original wording here.

In other words: the Sanaa Palimpest seems to have the more original wording here.

The fact that this very variant is indeed also attested in OTHER companion copies of the Quran, clearly also suggests that the scribe of the Sanaa Palimpsest's text type was not the only person to hear it, strengthening the evidence that the addition is the original wording.

In Sadeghi's original 2010 article, he found in the few folios he had examined of the Sanaa Palimpsest no examples of major pluses. Which meant that technically the Sanaa Palimpsest could have been a descendant from the Uthmanic text type.

But with the publication of Sadeghi & Goudarzi's edition, it is clear that there are indeed several major pluses in the Sanaa Palimpsest (including this one), which means that the text cannot descend from the Uthmanic text, and in this case retains the more original phrasing.

If you enjoyed this thread and want me to do more of it, please consider buying me a coffee.

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

twitter.com/PhDniX

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

twitter.com/PhDniX

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh