COP26 has been full of future warming numbers – 2.7C, 2.4C, 1.8C, etc – with new estimates released daily.

In a new @CarbonBrief analysis, @piersforster and I take a deep dive into climate outcomes – what they mean and how seriously we should take them carbonbrief.org/analysis-do-co… 1/

In a new @CarbonBrief analysis, @piersforster and I take a deep dive into climate outcomes – what they mean and how seriously we should take them carbonbrief.org/analysis-do-co… 1/

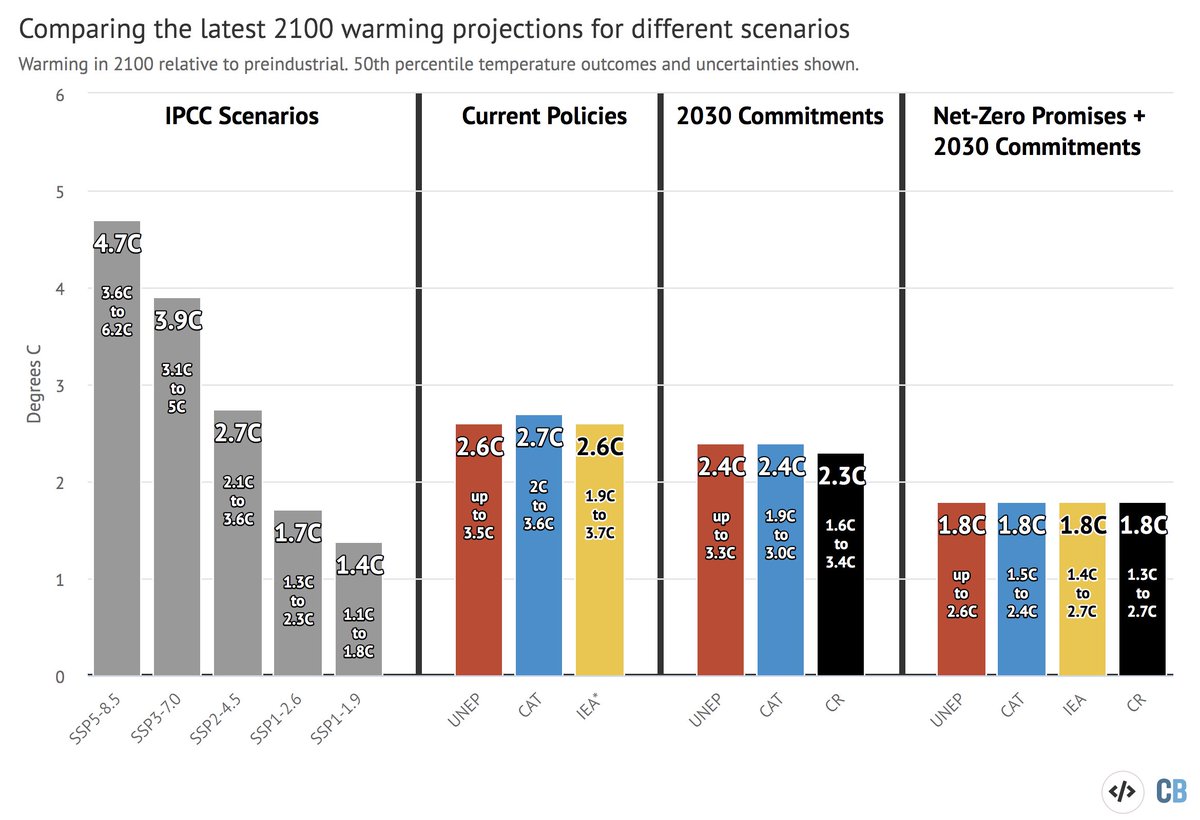

Future climate projections coming out of COP26 broadly consider three different scenarios: current policies, 2030 commitments (e.g. both unconditional and conditional NDCs), and longer-term net-zero promises. 2/

Four different groups have produced updated estimates of climate outcomes across these different scenarios: the @UNEP, @climateactiontr (CAT), @IEA, and the relatively new @ClimateRsrc (CR) team. 3/

It is noteworthy that these all show a high level of agreement: current policies put us on track for around 2.6C to 2.7C, meeting all 2030 commitments would put us on track for 2.4C, and long-term net zero promises put us on track for 1.8C. 4/

It is also encouraging that current policies – and falling costs of clean energy technologies – have moved us away from the most nightmarish futures of 4C or 5C warming examined in the most recent IPCC report, even though we remain far from limiting warming to well-below 2C. 5/

Each of these estimates has large uncertainties, due to climate system responses to our emissions – climate sensitivity and carbon cycle feedbacks. For example, while a current policy world puts us on track for around 2.6C, it could end up anywhere between 2C and 3.6C. 6/

While net-zero promises would in theory limit warming to below 2C, these promises aim for far in the future when none of the leaders making these promises will still be in office (or even alive). 7/

As only around a dozen of the 74 countries with net-zero commitments have actually formalized them into law, it is unclear how seriously these commitments should be taken or how likely they are to actually be achieved. 8/

Even meeting 2030 commitments and limiting warming to 2.4C by 2100 is by no means guaranteed; many countries are currently not on track to meet their NDCs, and many NDCs are themselves "conditional" and depend on financing or enhanced commitments by other countries. 9/

The world does not end in 2100, even though many models do, and the world will keep warming until CO2 emissions reach zero. In current policy or 2030 commitment scenarios where global temperatures remain above zero in 2100 the world will continue to warm into the 22nd century 10/

COP26 has seen a number of new pledges – to reduce methane, phase out coal faster, reduce financing for fossil fuels, and avoid deforestation – in addition to a number of country-level NDC updates. We provide a first assessment of new commitments over the past few weeks. 11/

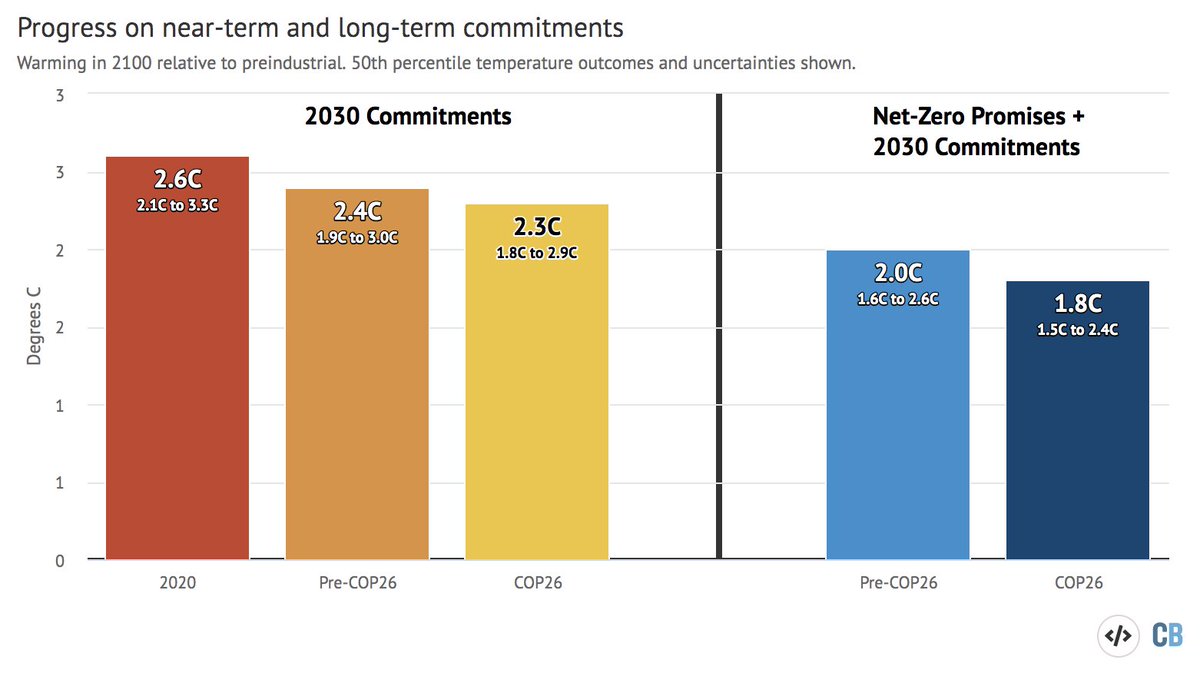

We find that the methane pledge and accelerated coal phaseout will likely reduce global temperatures by around 0.05C on top of existing 2030 commitments by countries. When combined with recent NDC updates this reduces 2100 temps by around 0.1C compared to pre-COP commitments. 12/

Back in 2020, near-term commitments by countries led in around 2.6C warming in 2100. Commitments made in leading up to COP26 reduced this to 2.4C, and we estimate that the world will be on track for 2.3C coming out of COP26 if both conditional and unconditional NDCs are met. 13/

Similarly, new long-term net-zero promises – driven in large part by India's new pledge to reach net-zero by 2070 – reduce projected warming from 2C to 1.8C if all net-zero promises are met. 14/

However, these long-term net-zero promises have a 'very big credibility gap'; we have seen relatively few updates to near-term 2030 commitments that would put countries on track to reach net-zero, and until we do it is hard to take these promises seriously. 15/

To have a reasonable chance of limiting warming to 1.5C by 2100, global emissions need to fall roughly in half by 2030. While country commitments around COP26 have modestly reduced warming outcomes and projected 2030 emissions, a massive gap still remains. 16/

Unless the emission curve can be bent down this decade, a flat emission trajectory locks in a reliance on net-negative emissions in the future – and brings into play their many risks around feasibility, governance and sustainability. 17/

Long-term net-zero promises by countries are less likely to be met unless there is a tangible increase in the strength of near-term commitments, and so far COP26 has proven to be long on promises and short on near-term action. 18/

For more details, check out our new analysis over at @CarbonBrief: carbonbrief.org/analysis-do-co…

Also, @chrisroadmap did a ton of work helping us translate the new methane and coal phaseout commitments into warming impacts.

*correction, where global emissions remain above zero.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh