So happy to see our article forthcoming at AEJ: Applied 🥳 This was the very first paper I ever worked on, quite a journey since we started collecting data in 2017 with @thomas_blncht and @lucas_chancel!

Here are five facts that we uncover about income inequality in 🇪🇺 and 🇺🇸: 👇

Here are five facts that we uncover about income inequality in 🇪🇺 and 🇺🇸: 👇

1/ Income inequality has risen faster in Eastern Europe than in Western/Northern Europe, but in no European country have top incomes boomed quite as fast as in the US.

2/ This holds when looking not only at European countries, but also at the European continent as a whole. Within-state inequality explains 97% of ineq in the US, while within-country inequality explains 83% of ineq in Europe today.

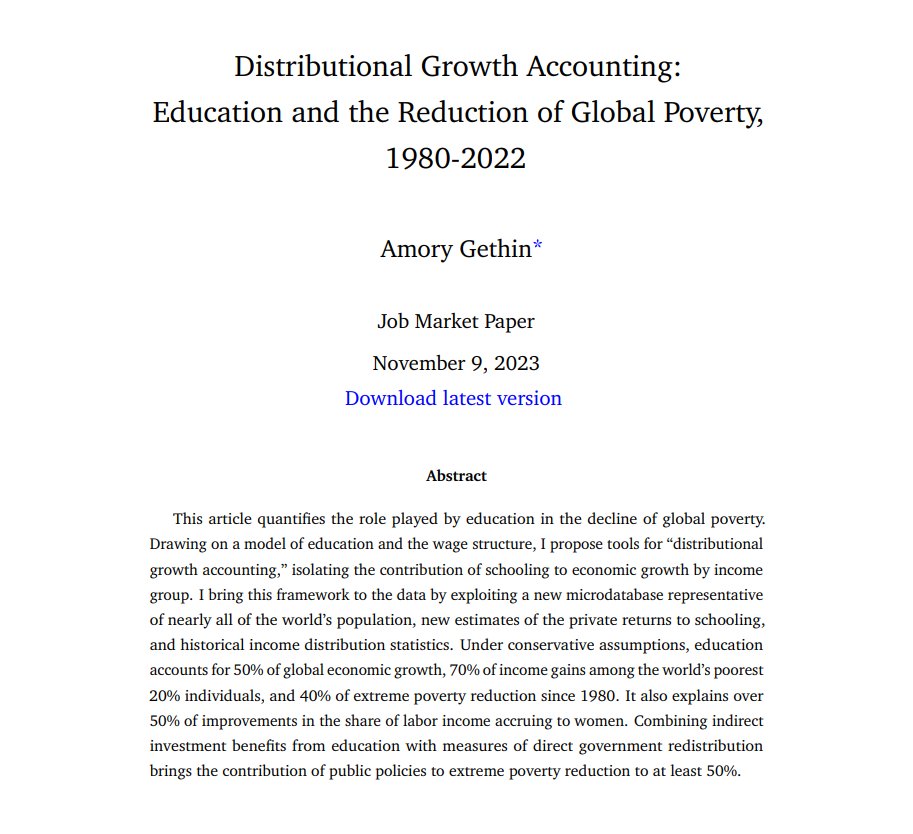

3/ The US tax system is MORE progressive than European countries'.

This is because the personal income tax is about as progressive in the US as in Western Europe (and much more progressive than in Eastern Europe), while indirect taxes are much lower.

This is because the personal income tax is about as progressive in the US as in Western Europe (and much more progressive than in Eastern Europe), while indirect taxes are much lower.

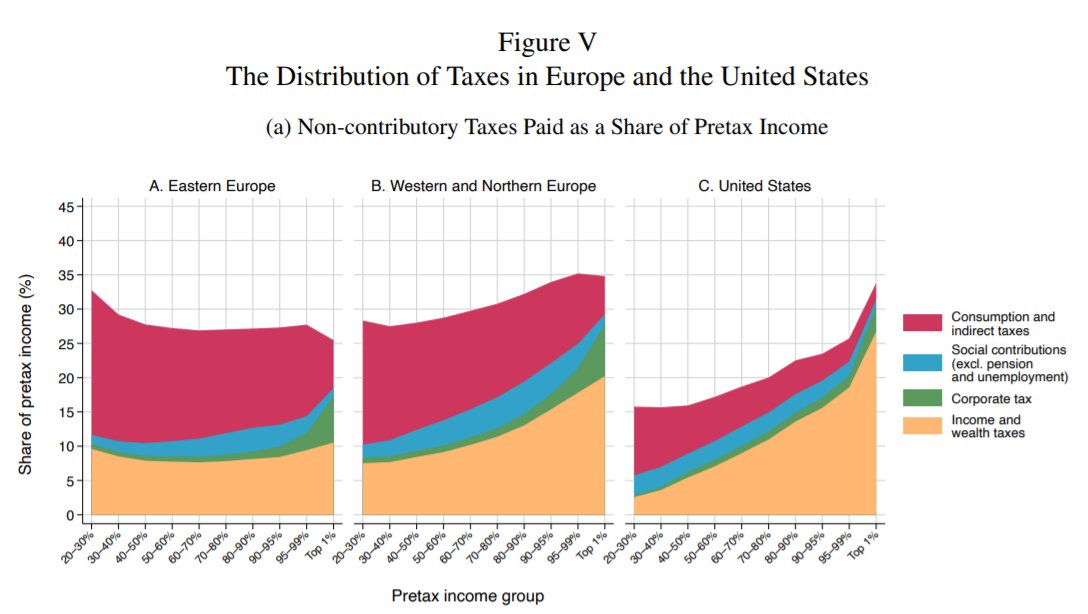

4/ As a result, despite lower transfers, the US tax-and-transfer system is MORE redistributive than that of any European country.

About 6% of the national income is transferred to the bottom 50% in the US, versus 4% in Sweden and 0% in Serbia.

About 6% of the national income is transferred to the bottom 50% in the US, versus 4% in Sweden and 0% in Serbia.

5/ Although the US tax-and-transfer system is more progressive, it is not progressive enough to close the huge inequality gap between the two regions.

Predistribution, not redistribution, explains why Europe is less unequal than the US today, both in pretax and posttax terms.

Predistribution, not redistribution, explains why Europe is less unequal than the US today, both in pretax and posttax terms.

Takeaway: policies aiming at reducing pretax inequalities (minimum wages, education policy, labor regulation, unions, etc.) matter substantially.

If you want to know more about the paper and the dynamics of specific countries, the latest working paper version of the article can be found here!

wid.world/document/why-i…

wid.world/document/why-i…

You can also visit our (slightly long) appendix, where we provide additional figures and detailed results on inequality and redistribution in the 38 European countries covered by the paper:

wid.world/document/techn…

wid.world/document/techn…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh