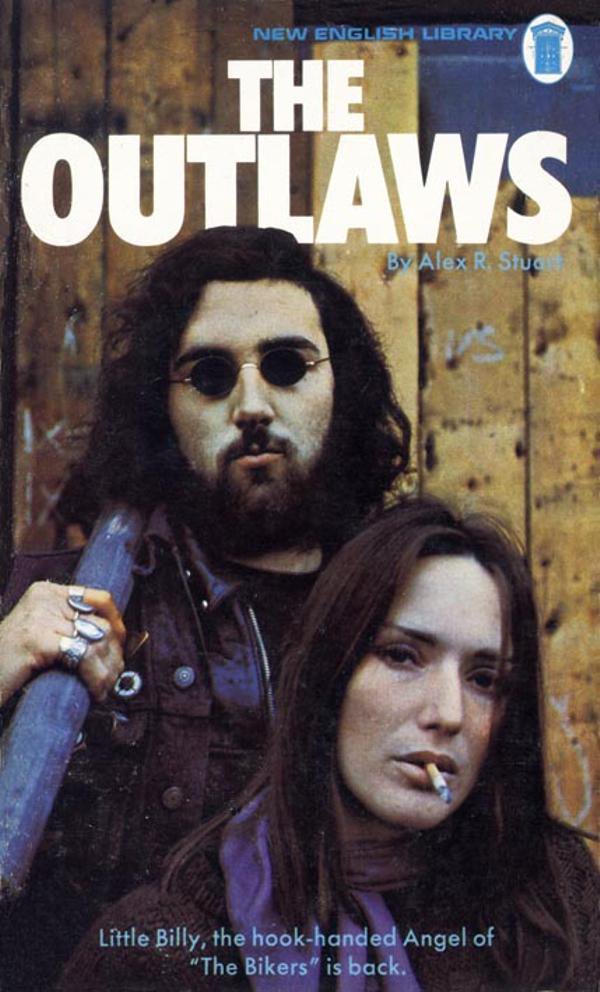

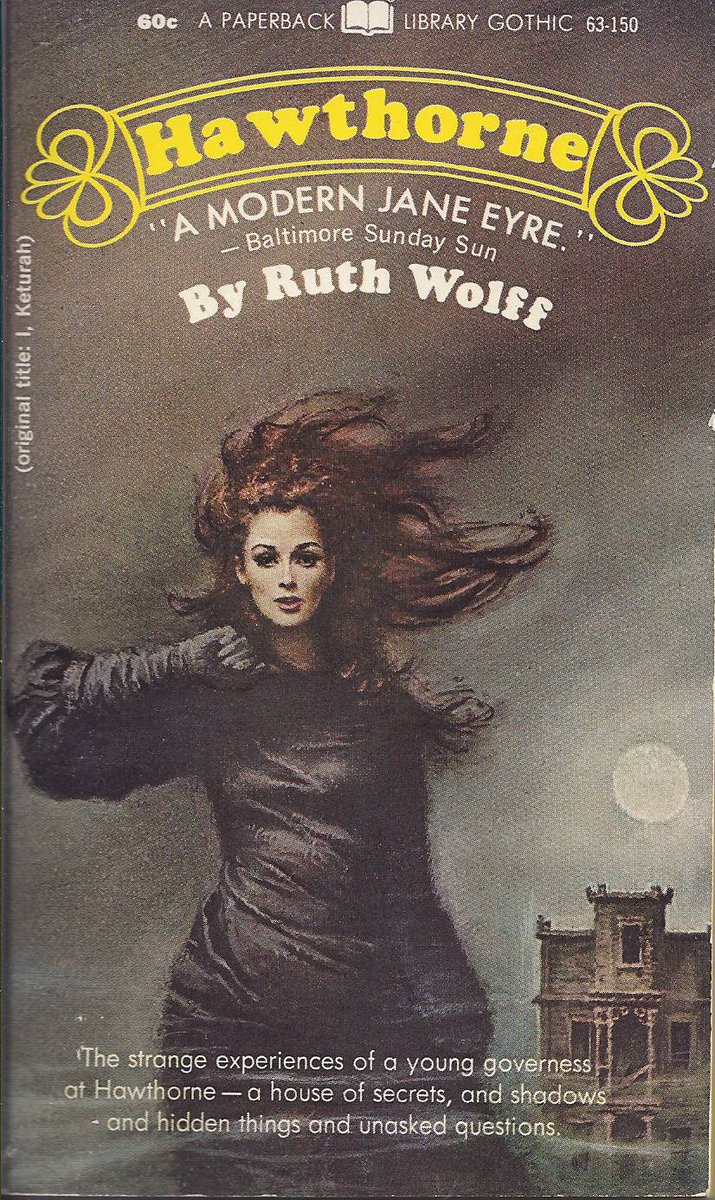

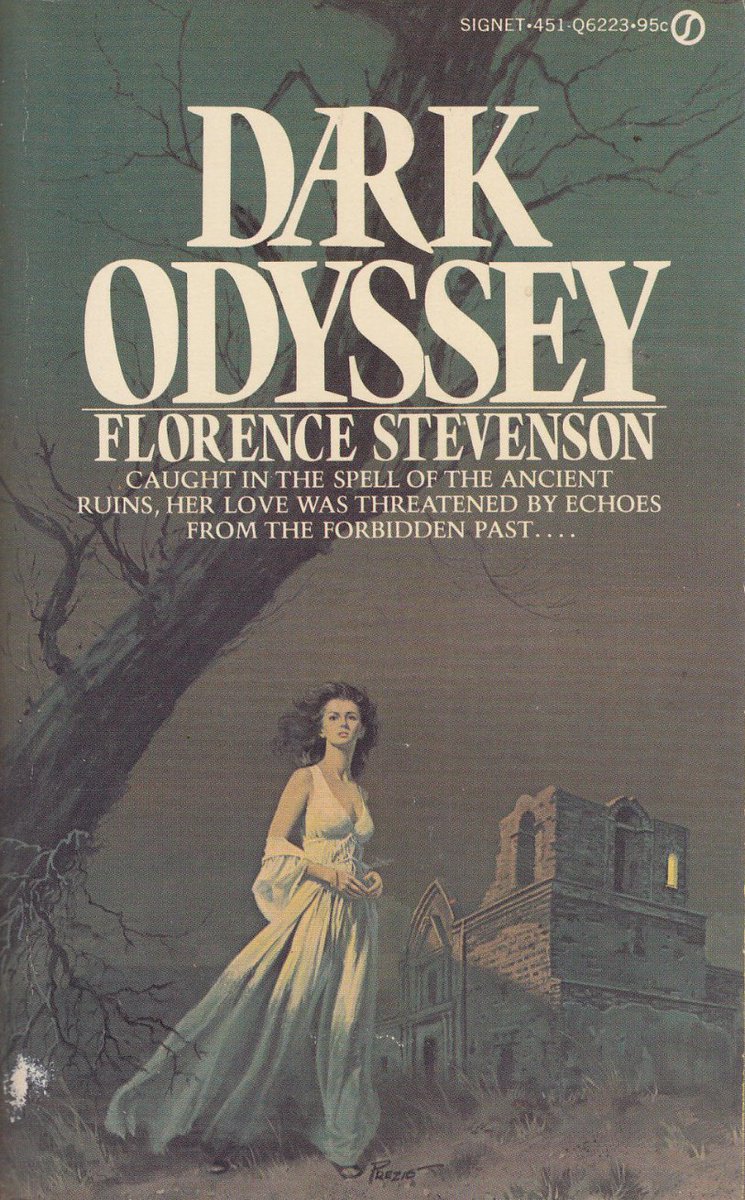

Today in pulp: a woman with great hair is fleeing a gothic house. Why?

Well this is a signal to the reader: they hold in their hands one of ‘those’ books – not a historical romance or a ghost story, but a modern gothic romance.

Let's learn more... #MondayMotivation

Well this is a signal to the reader: they hold in their hands one of ‘those’ books – not a historical romance or a ghost story, but a modern gothic romance.

Let's learn more... #MondayMotivation

New readers start here: what is a modern gothic romance? Well it's a romance story with strong supernatural themes, all tied to an atmospheric and foreboding building which our heroine must flee.

Actually it's a lot more complex than that...

Actually it's a lot more complex than that...

Firstly it has a long pedigree. Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto (1764) is usually acknowledged as the first gothic romance; set during the Crusades it follows Lord Manfred's fateful decision to divorce his wife and pursue his dead son's bride-to-be Isabella.

Otranto was a huge success, and was followed by many more gothic tales of love. Ann Radcliffe published The Mysteries of Udolpho in 1794; fair Emily is trapped in a castle of ghosts, legends and secret passageways as she tries to flee Lord Udolpho.

Matthew Lewis's 1796 novel The Monk took the gothic supernatural to new heights; demonic powers, witchcraft, a Bleeding Nun and the Spanish Inquisition all feature in this tale of the lust-demented monk Ambrosio.

You weren't expecting the Spanish Inquisition, were you?

You weren't expecting the Spanish Inquisition, were you?

By the 1800s the gothic romance had begun to develop along two distinct paths.

One was forged by the Brontë family...

One was forged by the Brontë family...

Wuthering Heights, published in 1847 is an ur-text of the gothic romance genre. Emily Brontë's novel of cruelty and passion amongst two generations of two families, the Earnshaws and the Lintons, all living in the shadow of the doomed love between Catherine and Heathcliffe.

Jane Eyre, published the same year by Charlotte Brontë, is a harrowing story of a heroine cruelly treated by almost everyone she meets, including Edward Rochester - the man she finally marries after he is humbled and almost destroyed by his first wife.

Many of the Brontë themes recur in subsequent gothic romances: the Byronic anti-hero, the governess who finds love, the cruel household, the relative who is locked away, the unhappy marriage. But the gothic themes are now of their time - no medieval castles any more.

The second gothic branch emerged earlier, and seemed poised to be the more successful. Frankenstein; or The Modern Prometheus, was published by Mary Shelly in 1818. It may be the first science fiction novel, but it was also instrumental in redefining the gothic.

Frankenstein is a story of great ambition, terror and pity. It is a love story as well as a revenge tragedy. But its major accomplishment was to plant the gothic into the soil of scientific rationality: the horrors that we create can outstrip the terrors of the supernatural.

By the late 19th century scientific gothic horror was in vogue: mad creations of man, crazed séances and mesmeric powers lurked in forbidding houses. The supernatural gothic turned instead towards vampires and etheric creatures.

Dracula, published in 1897, would cap the gothic novel genre: possessive love, the undead, blood ritual - it seemed that supernatural horror had triumphed over psychological terror. The vampire became the archetypal gothic trope.

But then... in 1938 the traditional gothic romance received a hefty jolt of life when Daphne du Maurier published her novel Rebecca - an instant publishing success that sold 3 million copies.

“Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again.” The manipulative first Mrs de Winter haunts the novel and the house, threatens the sanity and the life of the second Mrs de Winter, and finally reaches out from her watery grave to destroy the soul of her husband.

Rebecca was a success at around the same time that another pulp genre - the noir thriller - was beginning its ascendancy. Both genres deal with the cruelty of doomed love and how it destroys people; driving them to crime, insanity or death.

Gaslight, a 1938 play written by Patrick Hamilton and later made into a film, also effortlessly blended the Noir and the modern gothic together. It also provided one of the classic motifs of the genre - a woman manipulated into madness by a cruel lover.

Then in 1960 Mistress of Mellyn, by unknown author Victoria Holt, became an overnight publishing success. The story echoed both Rebecca and Jane Eyre: a governess takes a job in a foreboding Cornish mansion which is haunted by the dead wife of her mysterious employer.

Many believed du Maurier had written the book herself. Actually Mistress of Mellyn was penned by prolific British author Eleanor Hibbert. Her agent had convinced her to revive the gothic romance genre, believing there was still a market for this type of popular literature.

Soon Holt, along with Dorothy Eden, Joan Aiken, Marilyn Ross, Caroline Farr and many other authors were leading a gothic revival that would run up to the mid-80s. It was a revival sold by word of mouth, which helps explain why the cover art was so similar.

Joanna Russ reviewed the modern gothic romance in her 1973 essay Somebody’s Trying To Kill Me, based on the characters she found in a sample of genre novels from the 1960s: the brooding Super-Male, the virginal and passive Heroine, the sexual Other Woman and the patsy Other Male.

Russ was quite dismissive of modern gothic romance, seeing the main themes as emotional fear, incompetence and the passivity of the heroine. The drama unfolded in a supine way; the heroine was always at the mercy of others and always reacted by trying to be ‘good.’

For Russ these were pastiche paperbacks rather than real gothic; a mash-up of Jane Eyre and Rebecca where the heroine doesn’t do anything unless they do something wrong. They’re stories of naïve experience and overly-dark emotional relationships, steeped in cod-gothic trappings.

However the sheer range of modern gothics published between 1960 and 1985 – well over 1,000 – led to a range of plots being developed. Gothic heroines are often far from passive; in fact they're the active locus of the violent emotions and insatiable curiosities of the mind.

Critics also tend to overlook one of the main protagonists in modern gothic fiction: the house. It often directs and animates its inhabitants in ways they cannot fathom. In many ways the house is the character who shows the heroine the truth.

In the modern gothic the house often possesses place memory: the esoteric belief that buildings, trees and other objects can somehow store a record of traumatic past events, one that can be later sensed and recovered by gifted individuals.

This idea, derived from 19th century spiritualism, suggests that ghosts and other paranormal phenomena are not spirits of the deceased but simply fragments of an emotional recording that we sometimes glimpse when our own emotions are heightened: visions, voices, footsteps.

For me place memory is a key element of the modern gothic, as is the idea that it's the naïve outsider who is most sensitive to it. The ancestral home, which has born witness to the secrets and horrors of the family, shows her fragments of the secret as eerie sensations.

This is the uncanny in action: a psychological experience of something as unsettlingly familiar, rather than simply mysterious. It also tends to generate curiosity as much as revulsion, desire as much as dread. The German word for it is unheimlich – ‘un-homely’.

The symbols of the un-homely are eerie familiarities: doppelgängers, ghosts, déjà vu, familiar faces in ancient portraits, sounds from an empty room. In the modern gothic romance all these plot devices are used to elicit uncanny feelings in the reader.

The effect is unnerving when written well: existential terror rather than fully-fledged horror. We feel we are wandering uncertainly in a world we don’t quite understand anymore, unsure of ourselves and of others, sensing the echoes of something traumatic that has been cast out.

The heroine’s suffering at the hands of others in a gothic romance – hostility, abuse, gaslighting, insanity, mortal threat – is usually driven by these uncanny echoes, urging the unhappy people around her on to madness, violence and atrocity.

Yet on she goes. Whether she flees, endures or confronts it, the gothic heroine knows that the emotional disordering of her world is both irrational and real. It draws her down an irresistible track of curiosity, awe and fear until she finds its source.

And that's the reason gothic romance covers are all so similar: they all tell the same essential truth. That single-lit window in the tower is the house watching you, as you stumble along a dark path towards the irrational and unbounded. Perhaps you will survive it. Who knows?

Will the gothic romance make a comeback? It's a remarkably robust and flexible genre that's capable of great depth - both emotionally and psychologically. I'm sure its time will come again.

Mind how you flee now...

Mind how you flee now...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh