He was a laborer in Québec when the NHL came calling. The Boston Bruins offered him a tryout.

But Moe Hurwitz had other plans.

“There's no time to play hockey when millions of my brothers are getting killed in Europe.”

But Moe Hurwitz had other plans.

“There's no time to play hockey when millions of my brothers are getting killed in Europe.”

The children of Jewish immigrants Bella and Chaim endured the intolerance in Canada.

Still, after the declaration of war against Nazi Germany, five of them signed up to fight for Canada. Another joined the U.S. Army.

Still, after the declaration of war against Nazi Germany, five of them signed up to fight for Canada. Another joined the U.S. Army.

If, in the late 1930s, you frequented the bagel shops on The Main or read the sports pages in the Montréal Gazette, you would know of him.

He raced canoes down the St. Lawrence and stared down opponents on the rinks of Québec.

You would know Moe Hurwitz.

He raced canoes down the St. Lawrence and stared down opponents on the rinks of Québec.

You would know Moe Hurwitz.

And word was spreading south as he barreled into the Boston Olympics.

“For the visitors the untiring Moe Hurwitz was the bright star. Hurwitz, who alternated between forward and defense, bagged two of his team’s three tallies.”

“For the visitors the untiring Moe Hurwitz was the bright star. Hurwitz, who alternated between forward and defense, bagged two of his team’s three tallies.”

But Moe’s glare shifted to the Nazis.

Before he left home, he said goodbye to his brother.

“Don’t worry, Harry, I won’t be back. You look after yourself.”

Before he left home, he said goodbye to his brother.

“Don’t worry, Harry, I won’t be back. You look after yourself.”

April 1944. Harry was aboard HMCS Athabaskan near France when a German torpedo tore into the ship.

Covered in oil and clinging to debris as many of his shipmates died, Harry was plucked up by a ship bearing a swastika.

Covered in oil and clinging to debris as many of his shipmates died, Harry was plucked up by a ship bearing a swastika.

https://twitter.com/CAFinUS/status/1454637713320255489?s=20

Moe was training in England when he heard Harry was taken prisoner.

He was ready to fight any and every Nazi to save his brother.

He was ready to fight any and every Nazi to save his brother.

He’s in the fight by August at Cintheaux, France. With the Canadian advance stalled, the task to take the town falls to Moe’s troop.

They quickly knock out the German tanks and guns, but are without backup and facing a number of enemy soldiers.

Moe wasn't about to wait.

They quickly knock out the German tanks and guns, but are without backup and facing a number of enemy soldiers.

Moe wasn't about to wait.

“Like a flash, the Sergeant leaps out of his tank, Sten in hand and with a mighty shout he dashes up and down the hedge rooting prisoners out of their slit trenches.”

When an explosion injures his arm (and singes his moustache), he keeps rounding up enemy soldiers.

When an explosion injures his arm (and singes his moustache), he keeps rounding up enemy soldiers.

Reinforcements arrive and Moe’s troop hands off dozens of prisoners.

“Just like the movin’ pictures, eh, sir?”

“Just like the movin’ pictures, eh, sir?”

In Holland a month later, he jumps from his tank, clears three buildings, and charges two machine guns before rounding up more prisoners.

When a Canadian tank is hit and bursts into flames, he twice crawls 50 yards under heavy fire to rescue two fellow soldiers.

Typical Moe.

When a Canadian tank is hit and bursts into flames, he twice crawls 50 yards under heavy fire to rescue two fellow soldiers.

Typical Moe.

Leaping from his tank, “Geraldine,” and rushing machine guns. Flushing out enemy soldiers as though he were digging a puck out of the corner in the frigid rinks of Québec.

Then, in October 1944, he was behind enemy lines when he last made contact.

Moe was missing in action.

Then, in October 1944, he was behind enemy lines when he last made contact.

Moe was missing in action.

Five months later and Moe’s family still doesn’t know where he is. Imagine his mother writing this letter.

“…my son and another man are still the only ones not accounted for.”

“…my son and another man are still the only ones not accounted for.”

Moe wrote “Hebrew” on the things he carried. “Heb” was engraved on his identification discs. He wanted everyone to know he was Jewish.

Yet, his grave was marked with a cross.

Yet, his grave was marked with a cross.

Moe’s family and the Canadian Jewish Congress had to request a change and the matter was eventually rectified.

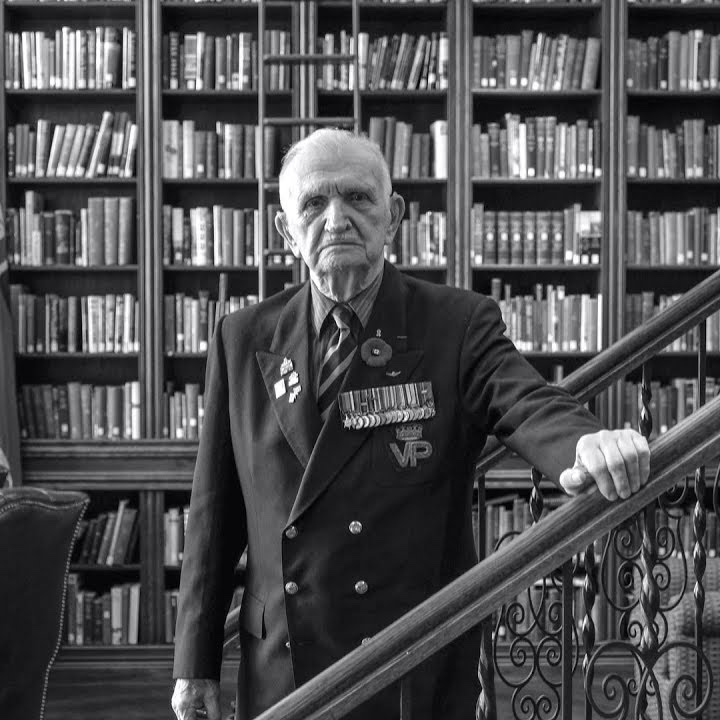

Harry survived the torpedoing of HMCS Athabaskan and the prisoner camp. He carried his brother with him every day until his death last year.

“My Sergeant brother Moe was the real hero.”

“My Sergeant brother Moe was the real hero.”

He wasn’t a Boston Bruin. He turned down the NHL and knew he wasn’t coming back.

The Military Medal. The Distinguished Conduct Medal. A humble, fearless, fighter.

We see you, Samuel Moses Hurwitz.

The Military Medal. The Distinguished Conduct Medal. A humble, fearless, fighter.

We see you, Samuel Moses Hurwitz.

Know their stories.

Know their fight.

See their light.

Learn more in @ebessner's Double Threat: Canadian Jews, the Military, and World War II.

Know their fight.

See their light.

Learn more in @ebessner's Double Threat: Canadian Jews, the Military, and World War II.

Moe Hurwitz is buried in the Bergen-Op-Zoom Canadian War Cemetery in the Netherlands.

https://twitter.com/project4_4/status/1324725923757887489

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh