Ibn Ḫālawayh (d. 381 AH) was one of the Ibn Mujāhid's students, and several important works of his have come down to us. One of these is his al-Ḥujjah fī al-Qirāʾāt as-Sabʿ "The Justification of the Seven Readings", and it is WEIRD. It keeps citing non-canonical readings! 🧵

The Ḥujjah could be called a "grammatical exegesis". It analyses all the variant readings where the seven readings disagree with one another, and explains why one would read one way or the other, and what those entail in meaning or grammatical choice.

Exegesis does this more commonly, but grammatical exegeses (or tawjīh/ḥujjah works works as one might call them) like these, are hyper-focused specifically on the points of disagreement.

Ibn Ḫālawayh ostensibly focuses on the seven readers canonized by his Teacher.

Ibn Ḫālawayh ostensibly focuses on the seven readers canonized by his Teacher.

But despite his book claiming to be there to explain the differences between the seven readings, he quite frequently cites variant readings that are not recited by any of the seven!

And it does not seem like Ibn Ḫālawayh was just confused about the details either.

And it does not seem like Ibn Ḫālawayh was just confused about the details either.

Ibn Ḫālawayh himself wrote a book on the seven readers + Yaʿqūb and in the margins wrote extensive notes on non-canonical readings he was aware of.

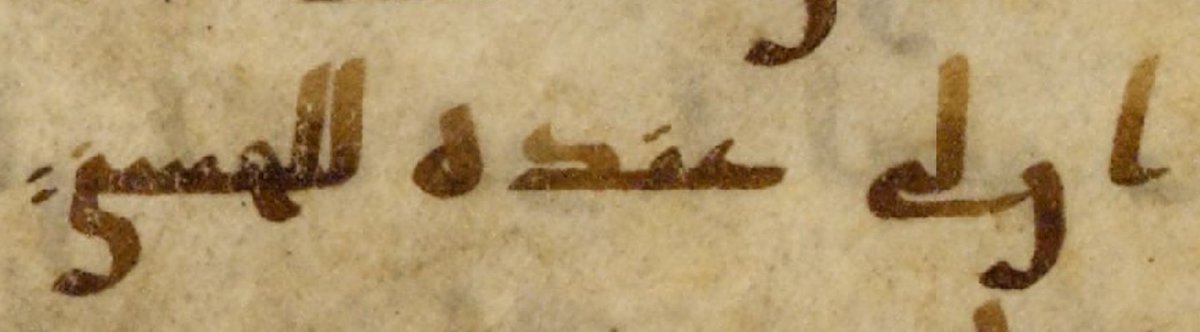

A gorgeous copy from his death year, presumably a copy from his autograph, is preserved at the @CBL_Dublin

viewer.cbl.ie/viewer/image/A…

A gorgeous copy from his death year, presumably a copy from his autograph, is preserved at the @CBL_Dublin

viewer.cbl.ie/viewer/image/A…

His marginal notes on non-canonical readings has also become a copy of a book on its own Muḫtaṣar fī Šawāḏḏ al-Qurʾān min Kitāb al-Badīʿ, which Gotthelf Bergsträßer edited.

He also wrote another grammatical exegesis, where he does not seem to cite non-canonical readings.

He also wrote another grammatical exegesis, where he does not seem to cite non-canonical readings.

Let's look at some cases of this in Sūrat al-ʾAnʿām which is a Sūrah I've been focusing on for a project together with @tafsirdoctor, where we consult this work quite extensively, which is the reason why I've run into the non-canonical readings being discussed there.

Q6:99 Ibn Ḫālawayh says is read both wa-ǧannātun min ʾaʿnābin and wa-ǧannātin min ʾaʿnābin. But none of the seven, nor the 10 read this way! It is a reading attributed to the non-canonical Kufan al-ʾAʿmaš, as Ibn Ḫālawayh records himself in his Badīʿ!

There is in fact a single strand transmission that attributes this reading to Šuʿbah, transmitter of ʿĀṣim, recorded by al-Dānī in his Jāmiʿ al-Bayān, but neither Ibn Ḫālawayh nor his teacher Ibn Mujāhid show any sign of awareness of this transmission.

Q6:105 Ibn Ḫālawayh seems to mention three readings dārasta, darasta and... durisat?! The canonical reading darasat is not discussed, even though he was clearly aware of it (in his Badīʿ), and he attributes durisat to al-Ḥasan al-Baṣrī.

Q6:139 Ibn Ḫālawayh discusses both ḫāliṣatun and ḫāliṣu-hū. All canonical readers have ḫālisatun. Ibn Ḫālawayh attributes the reading Ḫāliṣu-hū to prolific companion of the prophet Ibn ʿAbbās.

Q6:160 Ibn Ḫālawayh discusses

1. fa-lahū ʿašrun ʾamṯālahā

2. ʿašru ʾamṯālihā.

The second is the only reading among the seven. The first is Yaʿqūb by later sources, but Ibn Ḫālawayh does not report it for him, and attributes it to al-Ḥasan al-Baṣrī instead!

1. fa-lahū ʿašrun ʾamṯālahā

2. ʿašru ʾamṯālihā.

The second is the only reading among the seven. The first is Yaʿqūb by later sources, but Ibn Ḫālawayh does not report it for him, and attributes it to al-Ḥasan al-Baṣrī instead!

This is the only one of the four non-canonical readings I found in al-ʾAnʿām which Ibn Ḫālawayh does not discuss in his own catalogue of non-canonical readings. But it is attribute to al-ʾAʿmaš in al-Qabāqibī's book on the 14 readings.

So what's going on? The very fact that Ibn Ḫālawayh does not discuss these variants as canonical in his Badīʿ nor in his ʾIʿrāb al-Qirāʾāt al-Sabʿ wa-ʿIlaluh suggests that these are not the result of confusion or ignorance, but rather that he was including them on purpose.

Reading his introduction is not of much help. Ibn Ḫālawayh himself announces he'll be following the Seven canonical readers, and will comment only on disagreement between the famous readings and leave out the non-canonical rejected ones... but he doesn't always do that!

I don't really have an answer to what's going on. Have others looked at Ibn Ḫālawayh's Ḥujjah? Do such non-canonical reading mentions also happen elsewhere in the book? Or is al-ʾAnʿām exceptional? Sadly the editor does not note the odd nature of these variants in the footnotes

If you enjoyed this thread and want me to do more of it, please consider buying me a coffee.

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

@ShAmmarKhatib1 I think this is probably of interest to you, and perhaps you are aware of some other places in the Ḥujjah where Ibn Ḫālawayh discusses non-canonical readings!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh