Appreciate authors of the 🇧🇩 RCT finally releasing raw data.

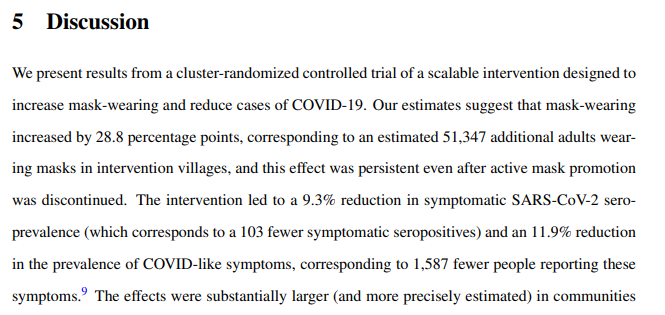

Dismayed at their topline conclusion on mask effectiveness that generated so much buzz

Out of ~340,000 ppl in mask and control arm.. the difference in symptomatic cases was 20 over 8 weeks.

benjamin-recht.github.io/2021/11/23/mas…

Dismayed at their topline conclusion on mask effectiveness that generated so much buzz

Out of ~340,000 ppl in mask and control arm.. the difference in symptomatic cases was 20 over 8 weeks.

benjamin-recht.github.io/2021/11/23/mas…

Brief summary for those interested. Bangladesh mask was a cluster RCT, (cluster because unit of randomization was a village) Treatment group had public policy intervention to increase use of masks, Control group was basically a poorly enforced govt. mask mandate)

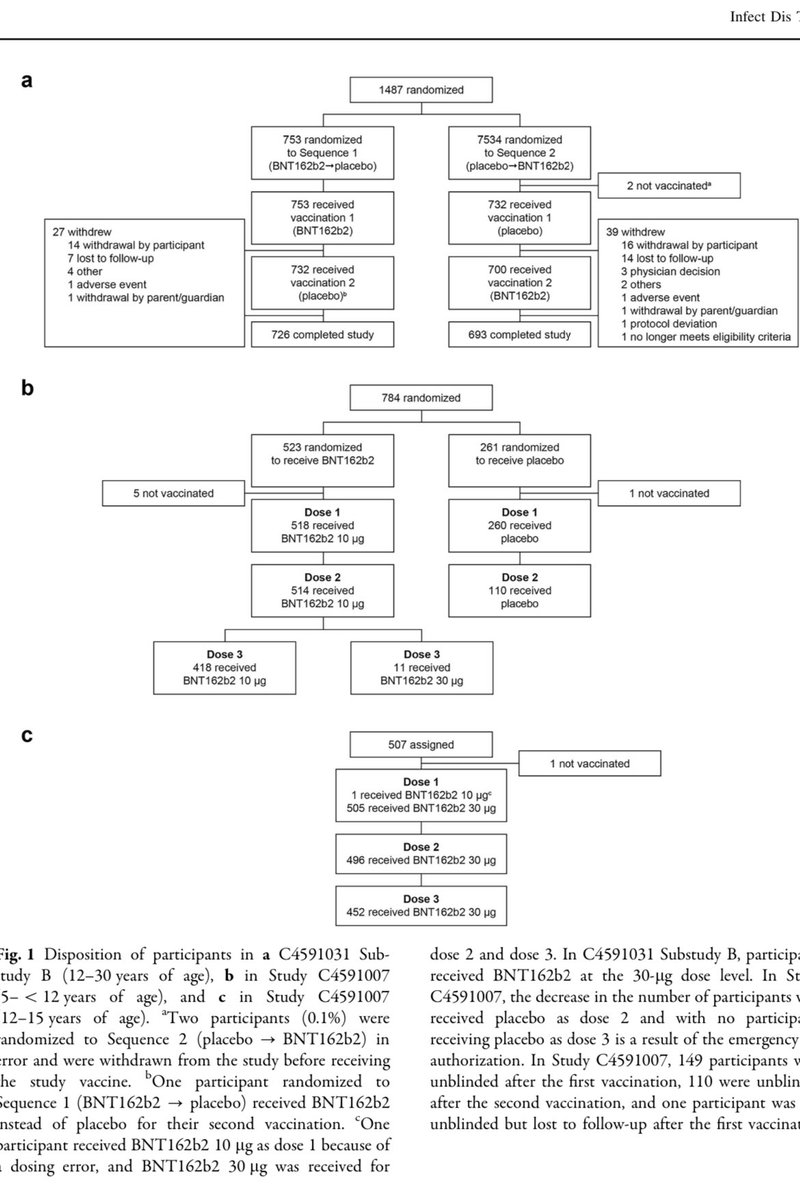

Per pre-print 342,126 individuals in study. Endpoint was COVID 19 +ve symptoms AND positive antibodies.

Key Table shows of ~150k pts in each arm, blood samples could only be collect from ~5k patients in each arm.

poverty-action.org/sites/default/…

Key Table shows of ~150k pts in each arm, blood samples could only be collect from ~5k patients in each arm.

poverty-action.org/sites/default/…

Unfortunately, nowhere in the paper is it noted how many of those tested were +ve for SarsCov2 Antibody. Weird. Since that is the primary endpoint.

This graph that made the rounds when the preprint came out? The #s used are coefficients from a model. They aren't 'real'

This graph that made the rounds when the preprint came out? The #s used are coefficients from a model. They aren't 'real'

The raw data was finally released. @beenwrekt 'crunched' the data to find the elusive raw # of symptomatic positives in treatment and control arm.

So of the ~10k blood samples available . 1086 were +ve in the treatment arm, 1106 +ve in the control arm

gitlab.com/emily-crawford…

So of the ~10k blood samples available . 1086 were +ve in the treatment arm, 1106 +ve in the control arm

gitlab.com/emily-crawford…

It would appear that the primary endpoint differs by 20 cases from the data provided. (Is poxXsymp the right column heading @Jabaluck ?).

One of the problems of the study is that despite the vast size of the study, the primary endpoint depends on ~5000 blood samples collected.

One of the problems of the study is that despite the vast size of the study, the primary endpoint depends on ~5000 blood samples collected.

So we are left to extrapolate from a 20 case difference tested in ~10,000 patients to a 300,000 patient study.. which gets us to a discussion made for headlines --> A policy intervention that increased mask wearing 29%, reduces symptomatic Sars COV2 by 9%!

But how robust can this possibly be? It seems a bit much to go from these small differences to the police tracking down and fining people who don't mask in public.. (this from the author of the Bangladesh RCT)

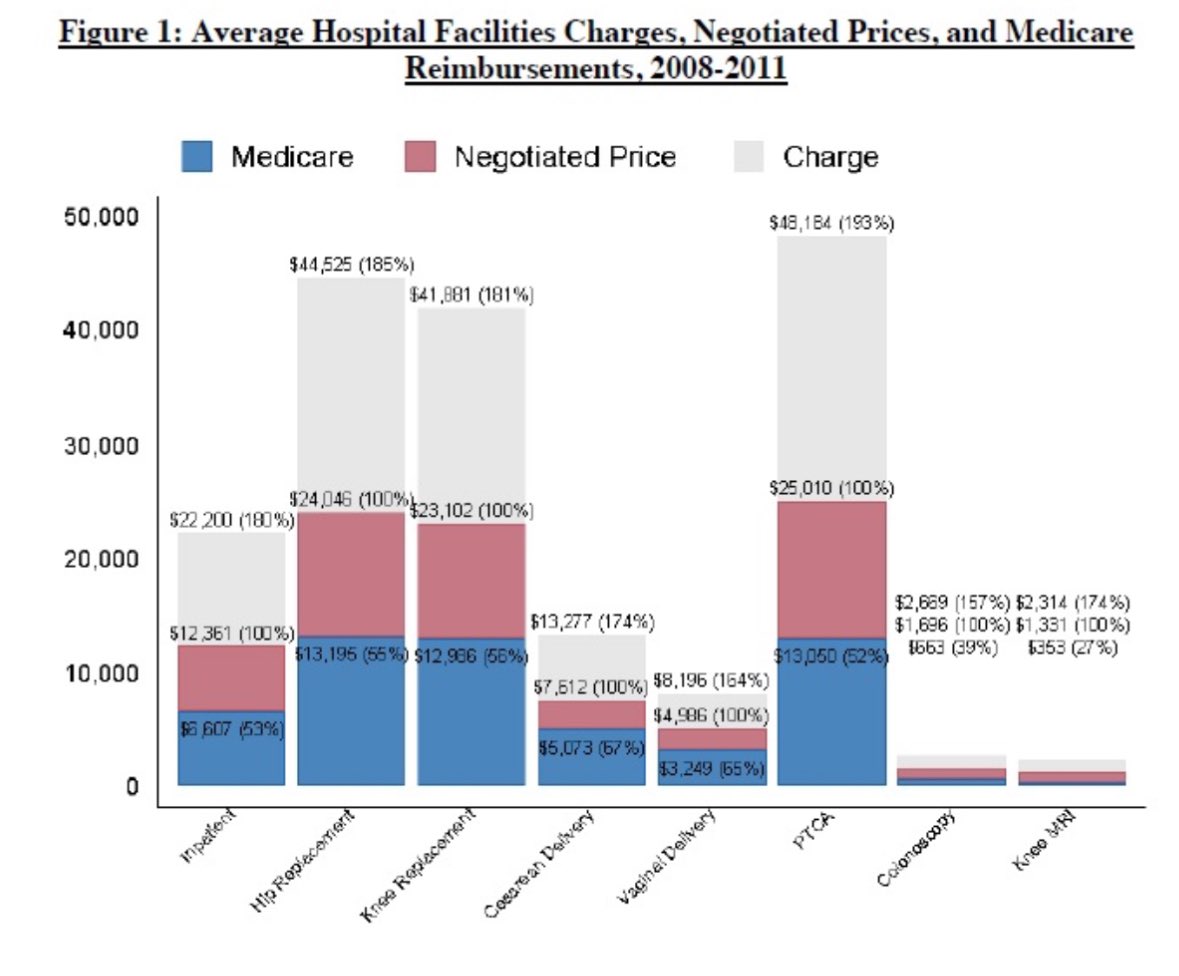

I wish I could say most health policy was based on stronger sauce than this.. What's a billion here or there when the taxpayer foots the bill?

By the way, most of these incidents that the US Attorney General, and almost Supreme Court Judge Merrick Garland wants to make a federal crime involve face covering incidents.

I find it pretty disconcerting as well that disagreeing with the conclusions of the Bangladesh RCT is disqualifying in some way when arguing in court!

The judge should have asked for the raw data!

The judge should have asked for the raw data!

https://twitter.com/UniversalMaski2/status/1452430888130777095?s=20

Statistical significance matters little when the outcomes isn't clinically significant. Especially relevant in very large trials when even small differences in 2 groups give highly statistically significant differences which may be clinically irrelevant.

This is a much smarter take.

https://twitter.com/BallouxFrancois/status/1433117571566419968?s=20

Another very smart take by @contrarian4data and @VPrasadMDMPH

https://twitter.com/contrarian4data/status/1459230804144316420

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh