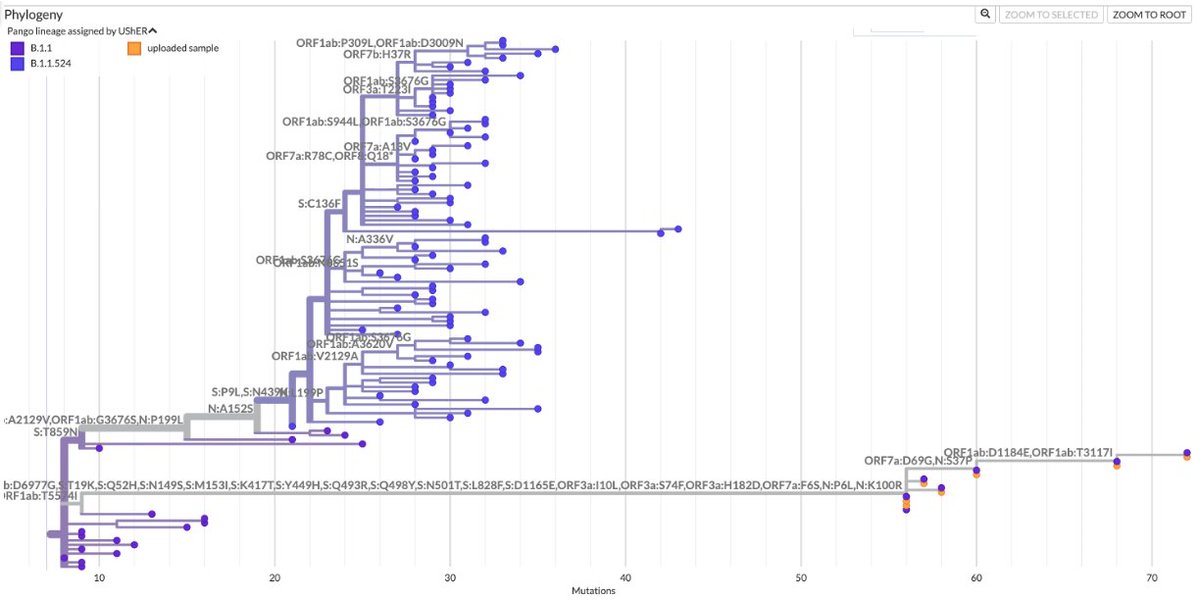

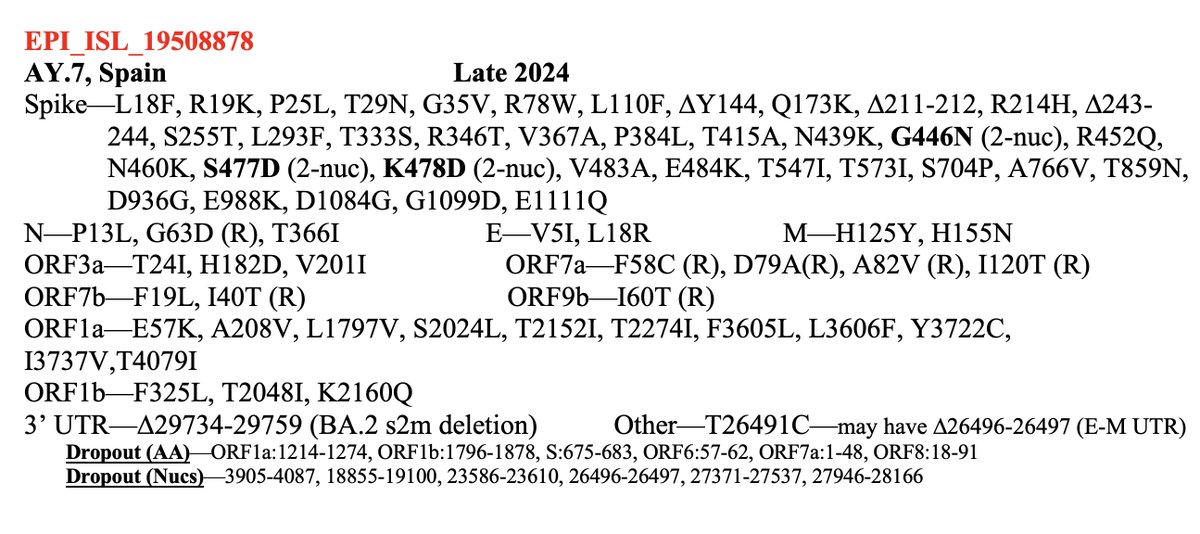

1/9 Something seemed familiar about the Q498R mutation. Then I remembered: @_b_meyer, examining in-vitro evolution of RBD mutations, predicted this mutation could emerge & lead to a variant with higher infectivity & immune evasion than any existing ones. nature.com/articles/s4156…

https://twitter.com/PeacockFlu/status/1463176821416075279

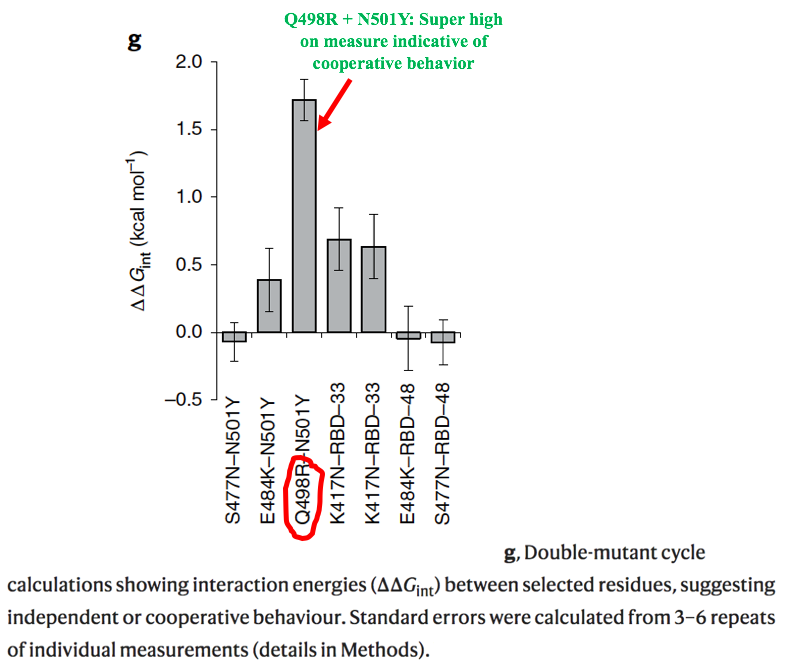

2/9 Q498R was not just one of many mutations they predicted: it was far & away their top candidate to become a major RBD mutation. It's the only novel mutation they mention in the abstract, noting that it requires the N501Y mutation to confer increased ACE2 binding affinity.

3/9 They used yeast to display human ACE2 receptors, then let various versions of SARS-CoV-2 S RBD compete against one another, with the highest binding-affinity RBDs advancing to the next round.

4/9 Random mutations were introduced in ways I'm not competent to explain, so I've included the relevant description in the screenshot below.

5/9 Mutations common in known VOCs quickly emerged, especially E484K and N501Y, which quickly became dominant. To me, this seems a good indication that their methods are valid & useful.

6/9 For library B5, they used ACE2 that required extremely high binding affinity, & this "resulted in the fixation of mutations E484K, Q498R and N501Y in all sequenced clones." Q498R was present in all the RBD variants with the highest binding affinity.

7/9 Figure 2f shows binding affinity on the x-axis and makes clear the ability of Q498R to increase ACE 2 binding affinity, hence their prediction that this mutation could emerge & spread.

8/9 Perhaps even more worrying, computer modeling by this team indicates that Q498R could confer a significant amount of immune evasion on any variant possessing it. No wonder this new SA variant is the first to worry @GuptaR_lab since the emergence of Delta.

9/9 I'm not an expert, so if I've made any errors or mischaracterized anything above, I welcome corrections from real experts. Besides @_b_meyer, the only other authors on the study on Twitter I could find were @Matthew_Gagne_ and @Nadav_Elad.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh