Teacher

"Be ruthless with systems and be kind to people."

Michael Brooks, 1983-2020

36 subscribers

How to get URL link on X (Twitter) App

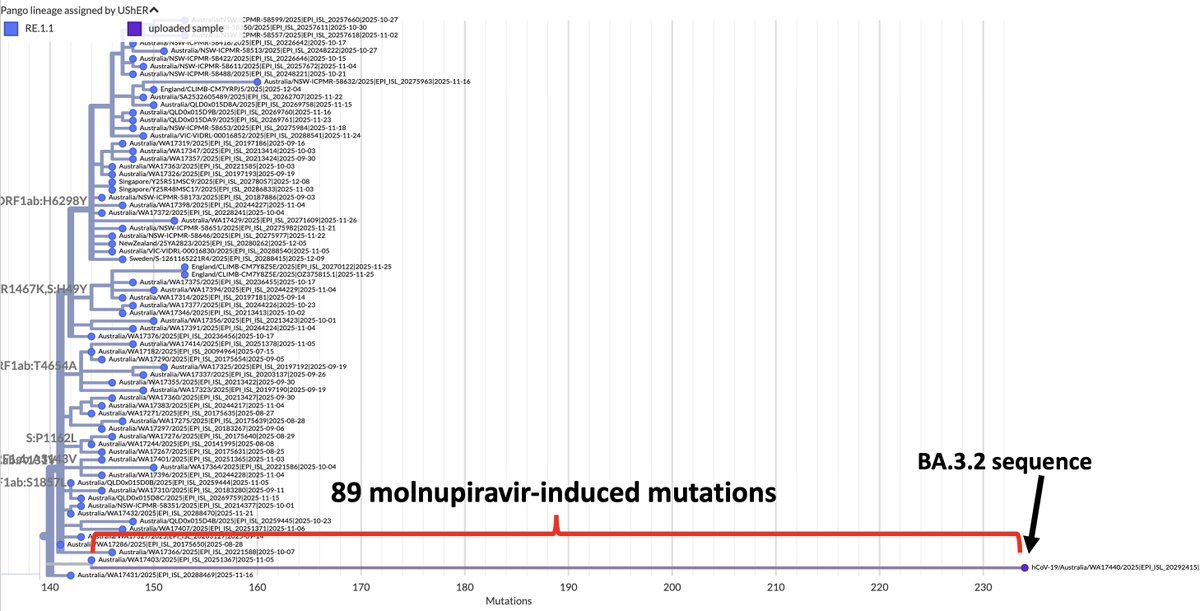

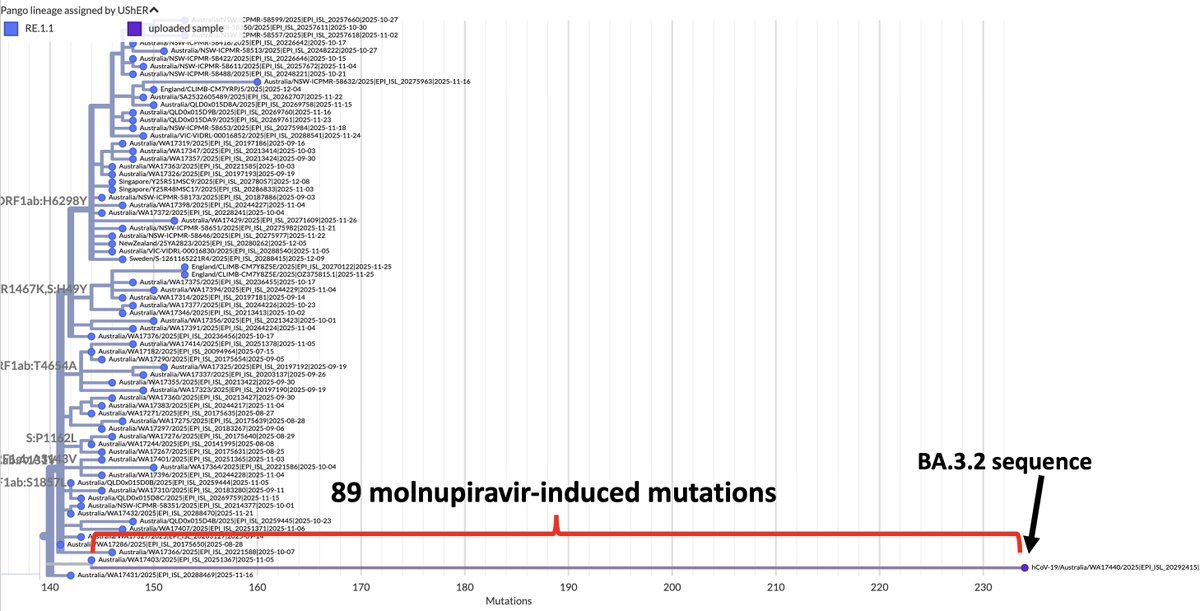

https://twitter.com/Tuliodna/status/2005638352381571577I would normally write a summary 🧵 of the BA.3.2 mutational analysis here, but as much of my contribution parallels my previous BA.3.2 threads I'll just link to those here, w/brief descriptions of each.

https://x.com/LongDesertTrain/status/1899647059872850369

Background on MOV: It's a mutagenic drug. Its purpose is to cause so many mutations that the virus becomes unviable & is cleared. But we've long known this often does not happen. Instead, the virus persists in highly mutated form & can be transmitted. 2/

Background on MOV: It's a mutagenic drug. Its purpose is to cause so many mutations that the virus becomes unviable & is cleared. But we've long known this often does not happen. Instead, the virus persists in highly mutated form & can be transmitted. 2/https://x.com/LongDesertTrain/status/1577256143281233921

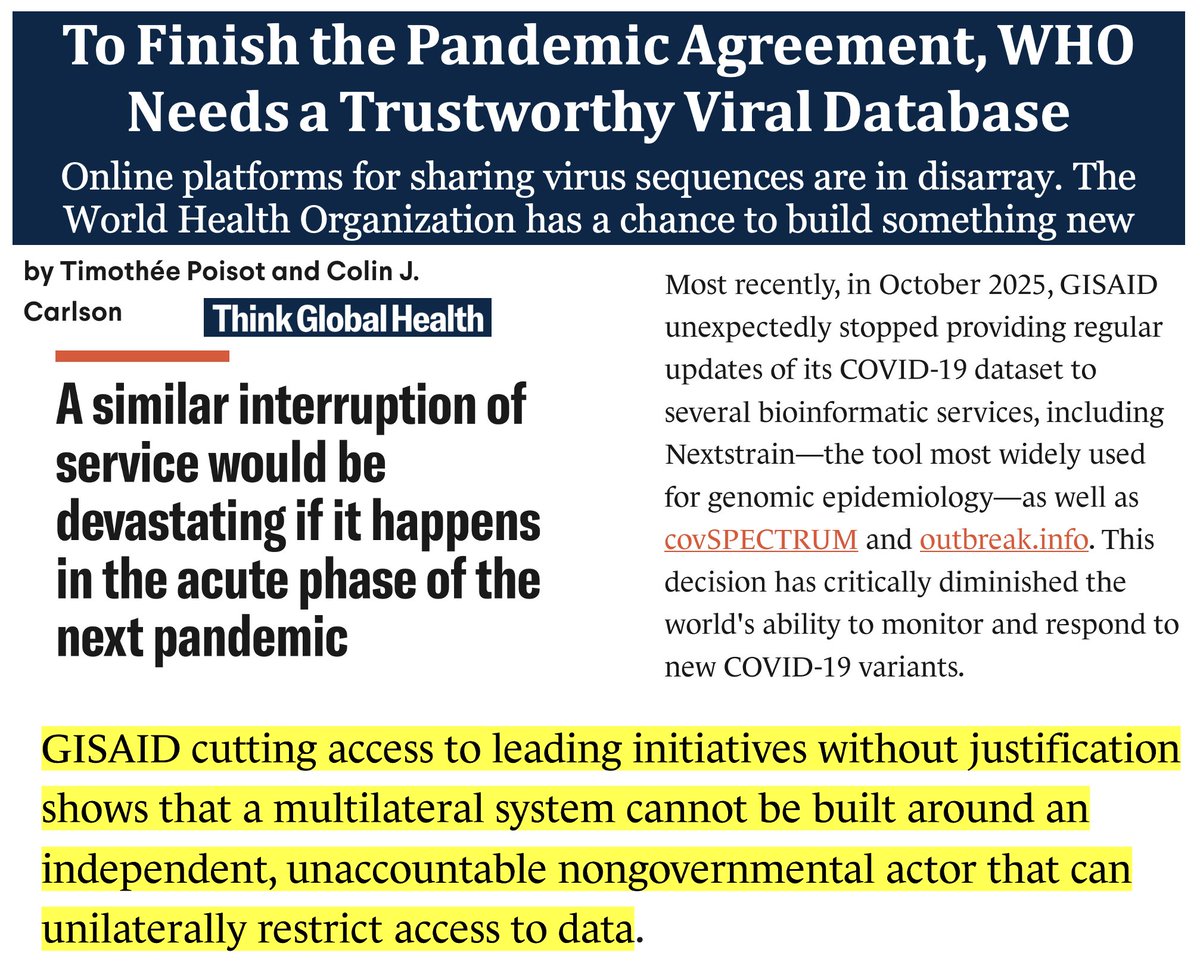

https://twitter.com/JPWeiland/status/2002487175884255270I use CovSpectrum & Nextstrain every day—& I'm not the only one. Every Covid thread I've ever posted here has relied partly on CovSpectrum & Nextstrain for information & visuals. These vital tools have now been stolen from us by a world-class grifter. 2/ thinkglobalhealth.org/article/to-fin…

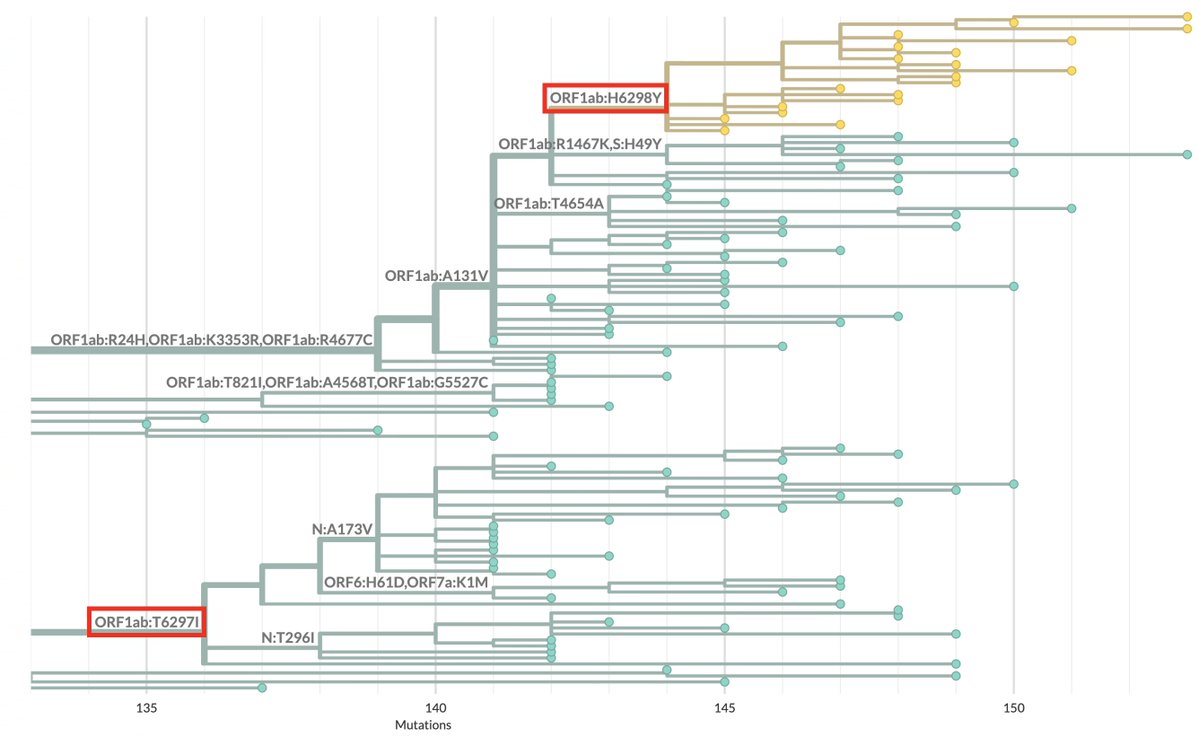

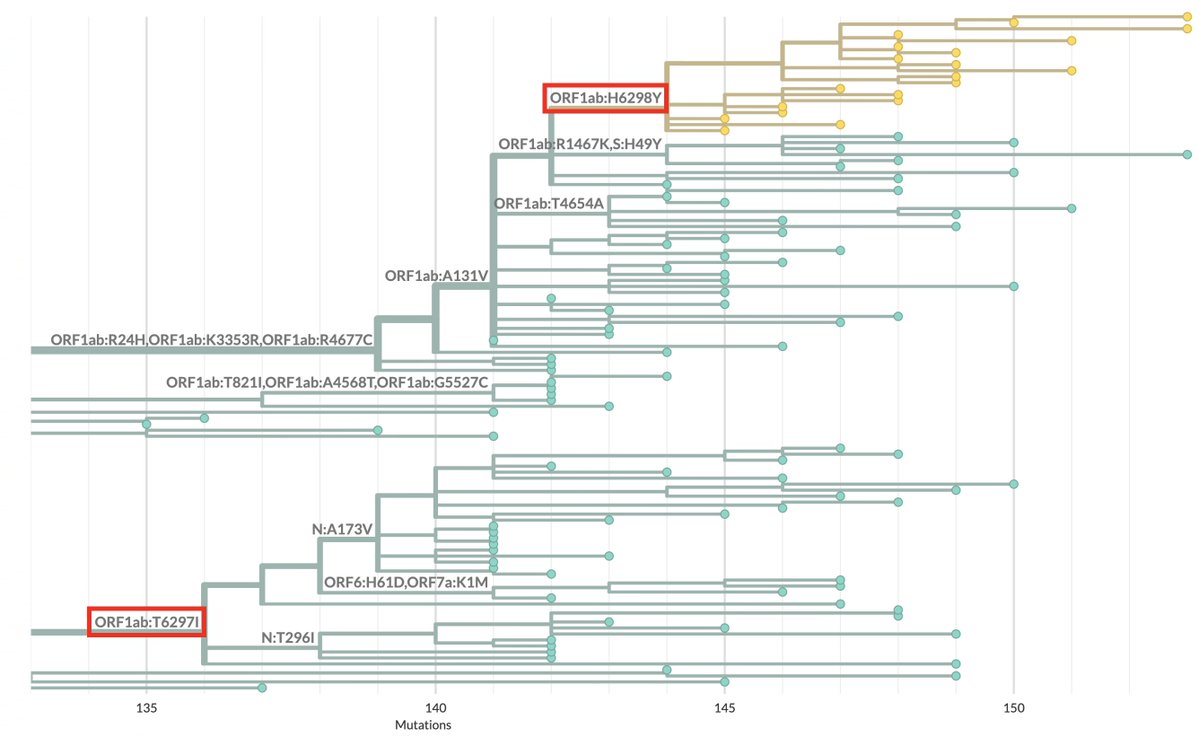

https://twitter.com/JosetteSchoenma/status/1998154156138545491One interesting (and possibly coincidental) aspect of the BA.3.2 tree: Two large branches have NSP14 mutations at adjacent AA residues—ORF1b:T1896I and ORF1b:H1897Y. 2/4

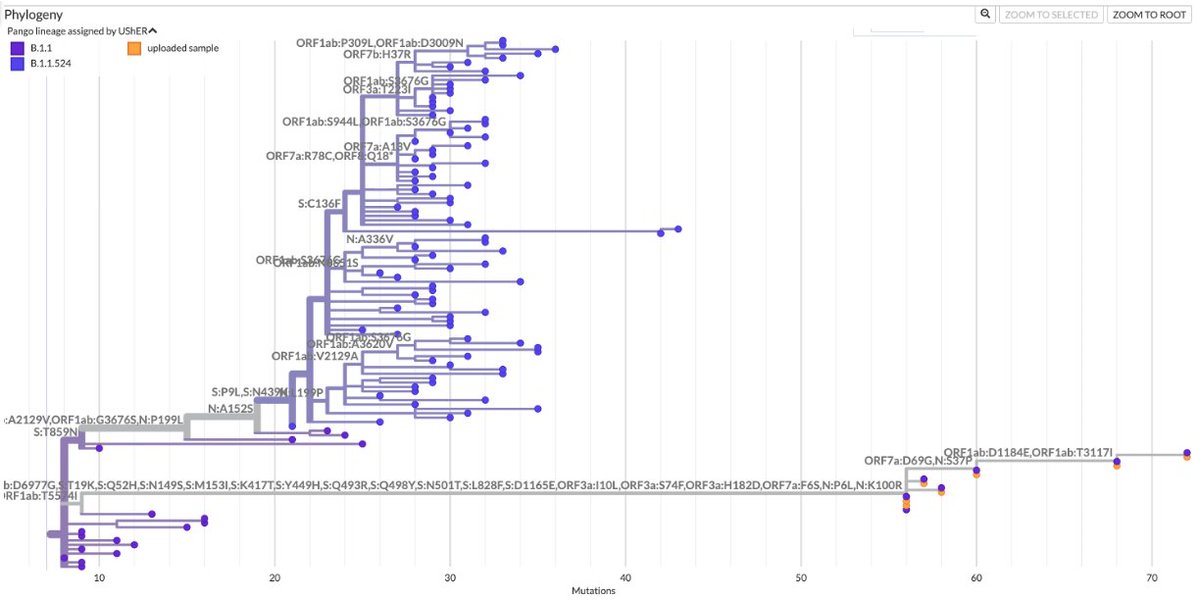

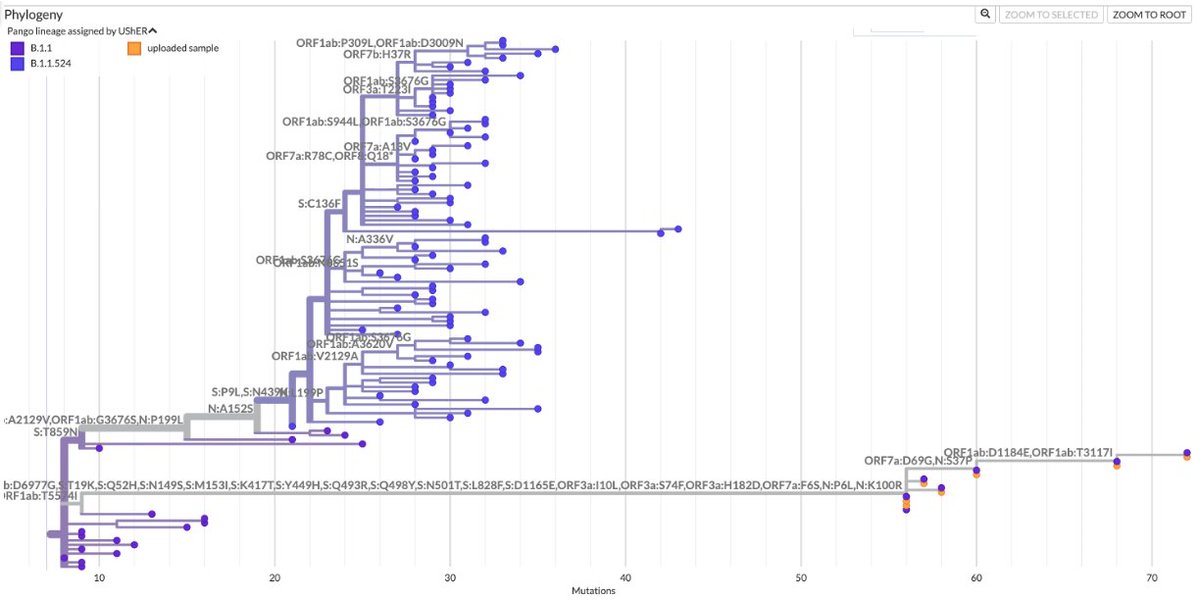

https://twitter.com/SolidEvidence/status/1991888519112093740The first instance involved a small cluster of sequences that hospitalized several people & resulted in the death of a young child in early 2022. More on this one later. 2/15

https://twitter.com/snpoehlm/status/1985998506365231105@StuartTurville has pointed out that WA delayed Covid spread longer than elsewhere in Australia. China has a somewhat similar immune history (as do other SE Asian countries). Perhaps BA.3.2 will do well in China once it arrives there? 2/4

https://x.com/StuartTurville/status/1983308264407503168

https://twitter.com/snpoehlm/status/1980953067777368569

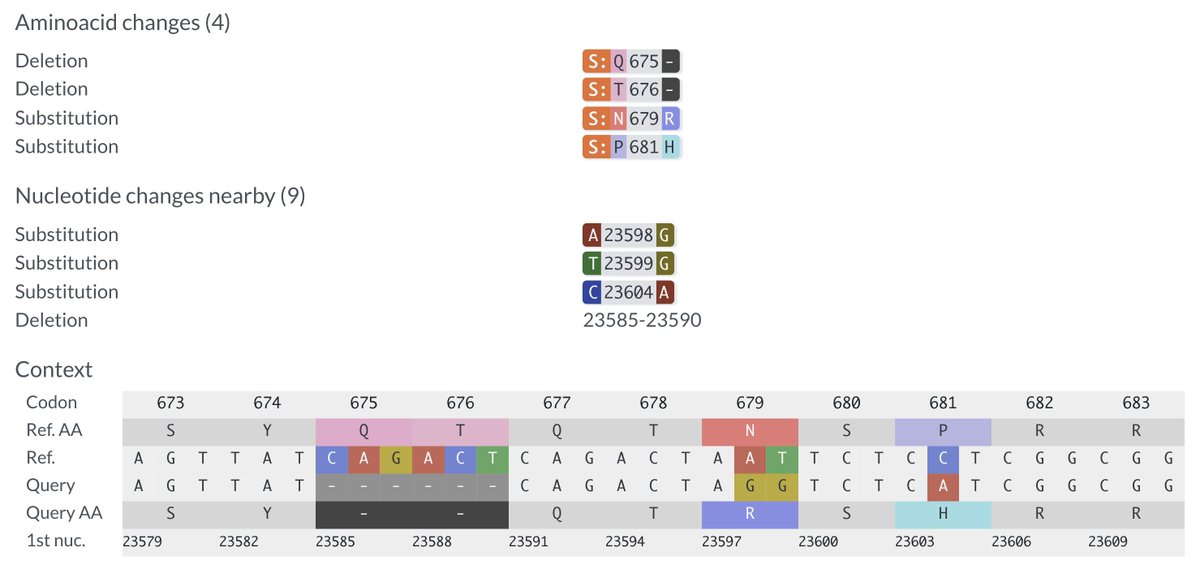

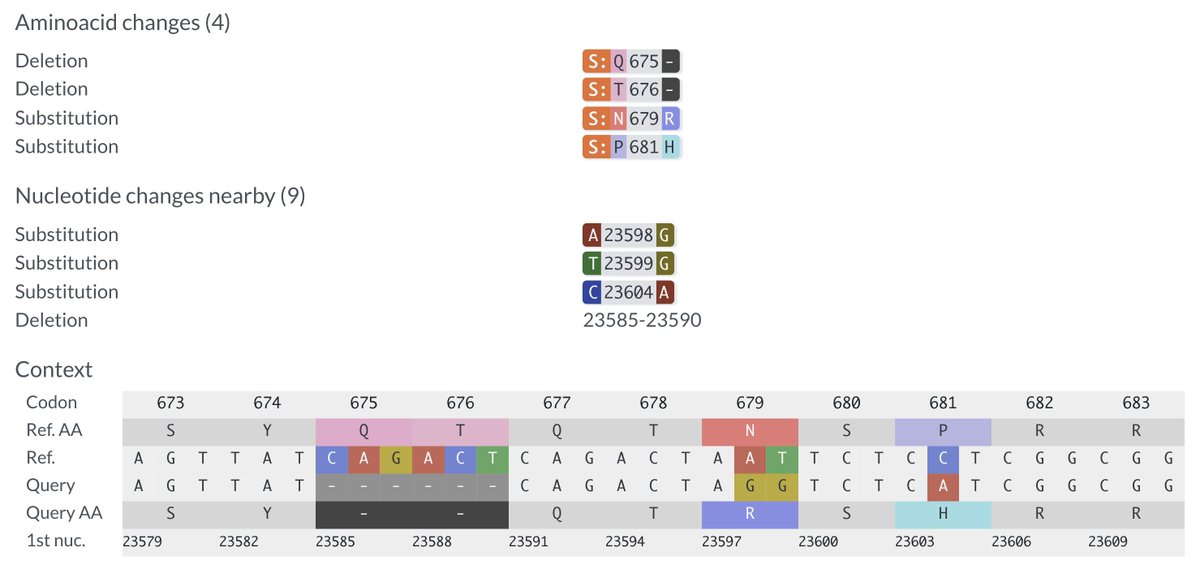

Work by @TheMenacheryLab looked at a similar, more extensive, deletion. They deleted both QT repeats plus the next AA (∆QTQTN). In Vero cells (monkey kidney cells), it produced extra-large plaques & outcompeted WT virus—similar to furin cleavage site (FCS)-deletion mutants. 2/12

Work by @TheMenacheryLab looked at a similar, more extensive, deletion. They deleted both QT repeats plus the next AA (∆QTQTN). In Vero cells (monkey kidney cells), it produced extra-large plaques & outcompeted WT virus—similar to furin cleavage site (FCS)-deletion mutants. 2/12

For those not following closely, here's a 🧵 I made about BA.3.2 (not yet designated at the time) that I made some months ago, when it first burst upon the scene. 2/7

For those not following closely, here's a 🧵 I made about BA.3.2 (not yet designated at the time) that I made some months ago, when it first burst upon the scene. 2/7https://x.com/LongDesertTrain/status/1899647059872850369

In South America, this may have already happened. Recent sequences are scarce, but they nearly all have some sort of FCS-weakening mutation, mostly S:S680P in XFG.3.4.1, but with several others (S680F, S680Y, R683Q, R683W) contributing as well. 2/4

In South America, this may have already happened. Recent sequences are scarce, but they nearly all have some sort of FCS-weakening mutation, mostly S:S680P in XFG.3.4.1, but with several others (S680F, S680Y, R683Q, R683W) contributing as well. 2/4

https://twitter.com/LongDesertTrain/status/1962980575054332049The ever-fertile mind of @Nucleocapsoid proffers the possibility that exosomes could be responsible for viral spread in some tissue reservoirs. I don't know much about this topic and so don't have much to say at the moment, but I'm trying to l learn. 2/

https://x.com/Nucleocapsoid/status/1962978769184153687

First, a brief summary of the relevant parts of the preprint. They examined 30 people (from NIH RECOVER cohort) for 6 months after they had Covid, taking detailed blood immunological markers at 3 time points. 20 had Long Covid (PASC), 10 did not (CONV). 2/ biorxiv.org/content/10.110…

First, a brief summary of the relevant parts of the preprint. They examined 30 people (from NIH RECOVER cohort) for 6 months after they had Covid, taking detailed blood immunological markers at 3 time points. 20 had Long Covid (PASC), 10 did not (CONV). 2/ biorxiv.org/content/10.110…

https://twitter.com/snpoehlm/status/1950476928760037506

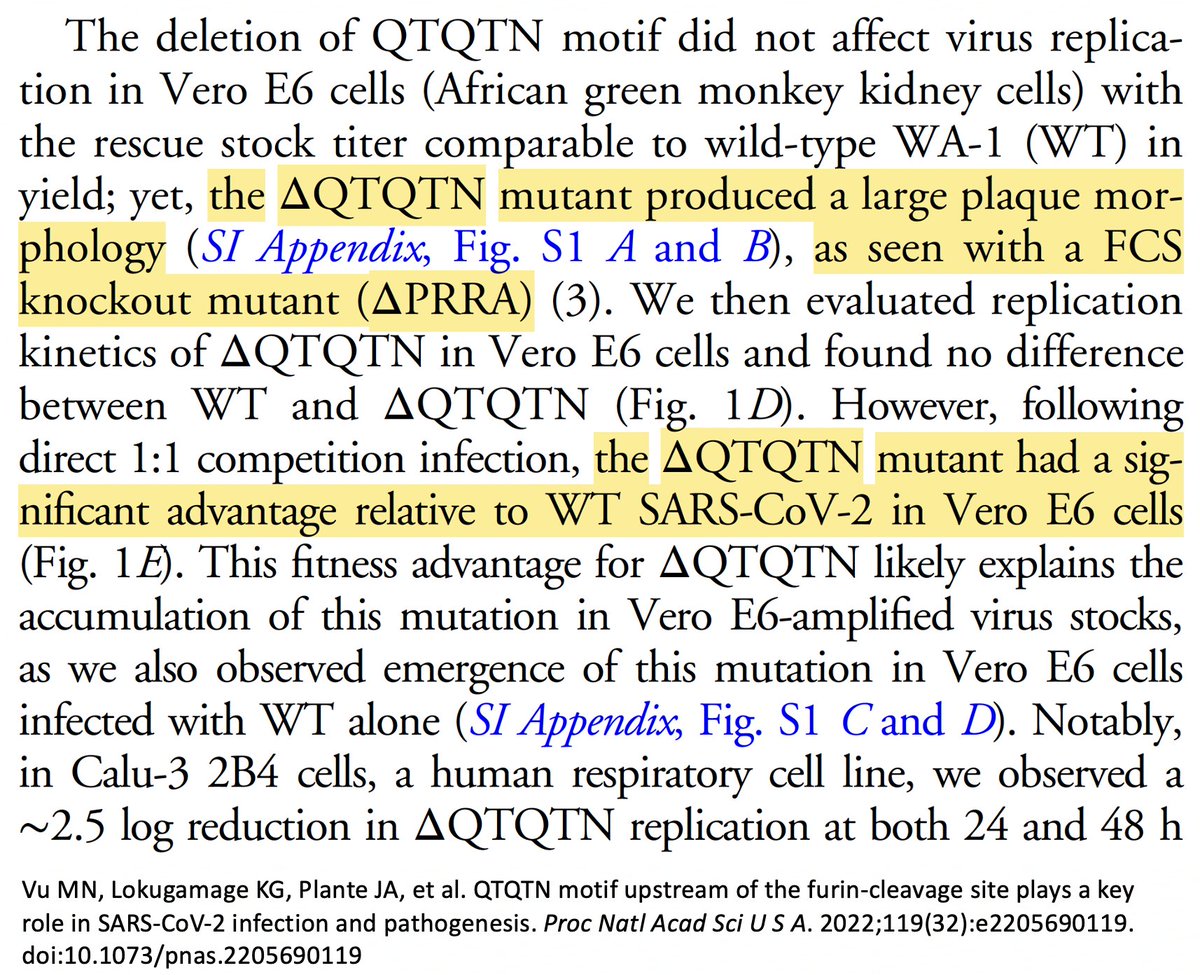

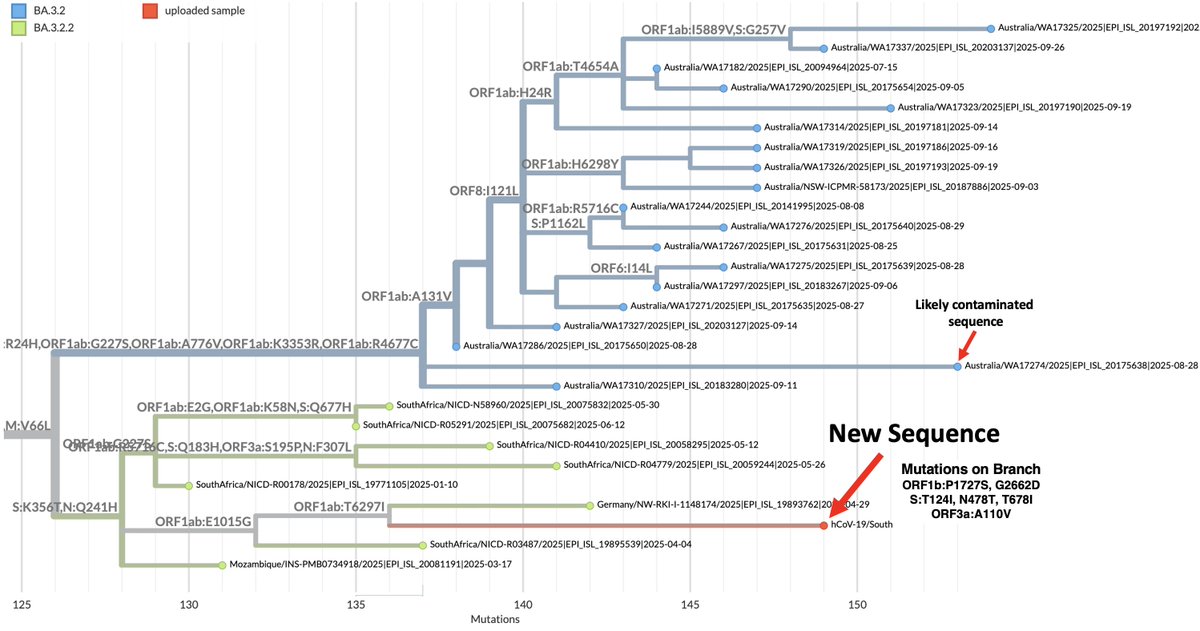

It was collected July 15, & is most closely related to the recent S African seqs from May & June.

It was collected July 15, & is most closely related to the recent S African seqs from May & June.

https://twitter.com/LongDesertTrain/status/1940384545741926911

Bottom line, in my view: BA.3.2 has spread internationally & is likely growing, but very slowly. If nothing changes, its advantage vs circulating lineages, which seem stuck in an evolutionary rut, will likely gradually grow as immunity to dominant variants solidifies... 2/9

Bottom line, in my view: BA.3.2 has spread internationally & is likely growing, but very slowly. If nothing changes, its advantage vs circulating lineages, which seem stuck in an evolutionary rut, will likely gradually grow as immunity to dominant variants solidifies... 2/9

https://twitter.com/LongDesertTrain/status/18996470598728503692 interesting aspects of the new BA.3.2:

This was a BA.3.2.1, the branch with S:H681R + S:P1162R (not S:K356T + S:A575S).

This was a BA.3.2.1, the branch with S:H681R + S:P1162R (not S:K356T + S:A575S).

When the B.1.595 was collected this infection was >1 yr old, w/no sign of Omicron. BA.1 ceased circulating ~1 year prior.

When the B.1.595 was collected this infection was >1 yr old, w/no sign of Omicron. BA.1 ceased circulating ~1 year prior.

https://x.com/LongDesertTrain/status/1837346366961451290…this preprint, along with another great study by the @DavidLVBauer, @theosanderson, @PeacockFlu & others prompted me to take a closer look...

BA.3.2 is a clear outlier on the antigenic cartography map—as expected given the enormous differences between its spike protein & every other circulating variant. 2/9

BA.3.2 is a clear outlier on the antigenic cartography map—as expected given the enormous differences between its spike protein & every other circulating variant. 2/9 https://x.com/LongDesertTrain/status/1899647059872850369

https://twitter.com/LongDesertTrain/status/1904881791468515590

They include the full panoply of NSP3, NSP12, & N muts I've written about previously. ORF1a:S4398L is the most common mutation in the 4395-4398 region, this has ∆S4398, a rarity also seen in a few other extremely divergent seqs w/this constellation. 2/6

They include the full panoply of NSP3, NSP12, & N muts I've written about previously. ORF1a:S4398L is the most common mutation in the 4395-4398 region, this has ∆S4398, a rarity also seen in a few other extremely divergent seqs w/this constellation. 2/6 https://x.com/LongDesertTrain/status/1781121824845099318