So in what reading tradition have these Quranic quotes been written you ask? Well I wondered the same thing! Let's have a look shall we?

Q18:81 (red) ʾan yubaddilahumā = Nāfiʿ, ʾAbū Jaʿfar, ʾAbū ʿAmr. Rest has yubdilahumā (also in black)

Q18:81 (red) ʾan yubaddilahumā = Nāfiʿ, ʾAbū Jaʿfar, ʾAbū ʿAmr. Rest has yubdilahumā (also in black)

https://twitter.com/joumajnouna/status/1465342422557286400

Q18:81 (red & black) ruḥman (Majority); Ibn ʿĀmir, ʾAbū Jaʿfar: ruḥuman.

So red it can't be ʾAbū Jaʿfar. (ʾAbū ʿAmr and Nāfiʿ left).

Black could still be anyone but Ibn ʿĀmir, ʾAbū Jaʿfar Nāfiʿ andʾAbū ʿAmr.

So red it can't be ʾAbū Jaʿfar. (ʾAbū ʿAmr and Nāfiʿ left).

Black could still be anyone but Ibn ʿĀmir, ʾAbū Jaʿfar Nāfiʿ andʾAbū ʿAmr.

Q18:85

red: fa-ttabaʿa (majority), fa-ʾatbaʿa (ʿĀṣim, Ḥamzah, al-Kisāʾī, Ḫalaf and ibn ʿĀmir)

Black: might be fa-ʾatbaʿa, a bit unclear. If so the reading is Kufan.

red: fa-ttabaʿa (majority), fa-ʾatbaʿa (ʿĀṣim, Ḥamzah, al-Kisāʾī, Ḫalaf and ibn ʿĀmir)

Black: might be fa-ʾatbaʿa, a bit unclear. If so the reading is Kufan.

Q18:86

Here the black text clearly follows ḥāmiyatin... but the red vocalisation appears to hamzah, which is only consistent with ḥamiʾatin, which does not help us narrow it down. That's the reading of Nāfiʿ, ibn Kaṯīr, ʾAbū ʿAmr, Yaʿqūb and Ḥafṣ.

Here the black text clearly follows ḥāmiyatin... but the red vocalisation appears to hamzah, which is only consistent with ḥamiʾatin, which does not help us narrow it down. That's the reading of Nāfiʿ, ibn Kaṯīr, ʾAbū ʿAmr, Yaʿqūb and Ḥafṣ.

Q18:88:

Red: ǧazāʾu l-ḥusnā (majority reading)

Black: ǧazāʾan-i l-ḥusnā: Yaʿqūb, Ḥamzah, al-Kisāʾī, Ḫalaf, Ḥafṣ

Black is starting to look clearly Kufan. Red might still be Nāfiʿ or ʾAbū ʿAmr (I'm quite sure it's gonna be ʾAbū ʿAmr).

Red: ǧazāʾu l-ḥusnā (majority reading)

Black: ǧazāʾan-i l-ḥusnā: Yaʿqūb, Ḥamzah, al-Kisāʾī, Ḫalaf, Ḥafṣ

Black is starting to look clearly Kufan. Red might still be Nāfiʿ or ʾAbū ʿAmr (I'm quite sure it's gonna be ʾAbū ʿAmr).

Q18:93

Red & Black: bayna s-saddayni: reading of Ibn Kaṯīr, ʾAbū ʿAmr, and Ḥafṣ. The rest reads s-suddayni.

Therefore:

Red = ʾAbū ʿAmr

Black = Ḥafṣ ʿan ʿĀṣim

The fact the two vocalisations represent different readings is yet another argument they are not contemporary.

Red & Black: bayna s-saddayni: reading of Ibn Kaṯīr, ʾAbū ʿAmr, and Ḥafṣ. The rest reads s-suddayni.

Therefore:

Red = ʾAbū ʿAmr

Black = Ḥafṣ ʿan ʿĀṣim

The fact the two vocalisations represent different readings is yet another argument they are not contemporary.

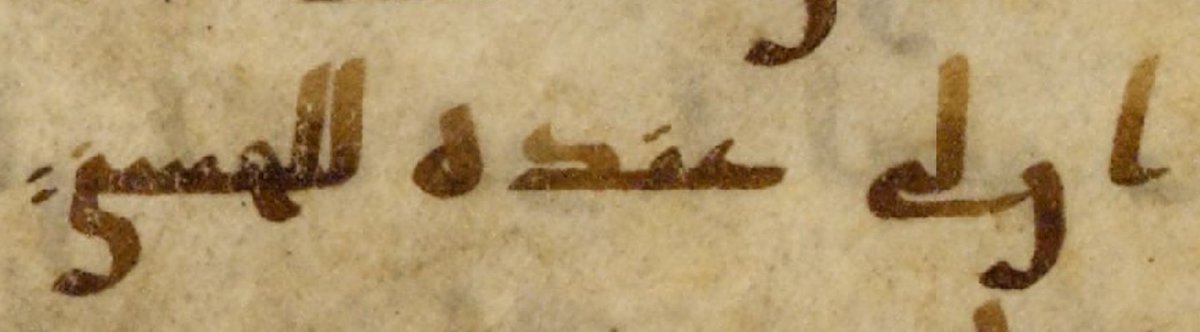

Anyone who can read the Persian: it would be cool if we could figure out which of the two readings the Persian commentary had in mind and whether it aligns with either the red or the black vocalisation!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh