Today in pulp... I look back at that perennial Xmas stocking filler and all-round cheap and easy present from your Auntie the #Christmas Annual!

They're in the shops now...

They're in the shops now...

If you're not from the UK you might be slightly baffled by the term 'Christmas Annual.' Basically it's a hardback A4 sized book themed around a comic, tv show or movie. It's full of stories, comic strips and various filler items for kids to read.

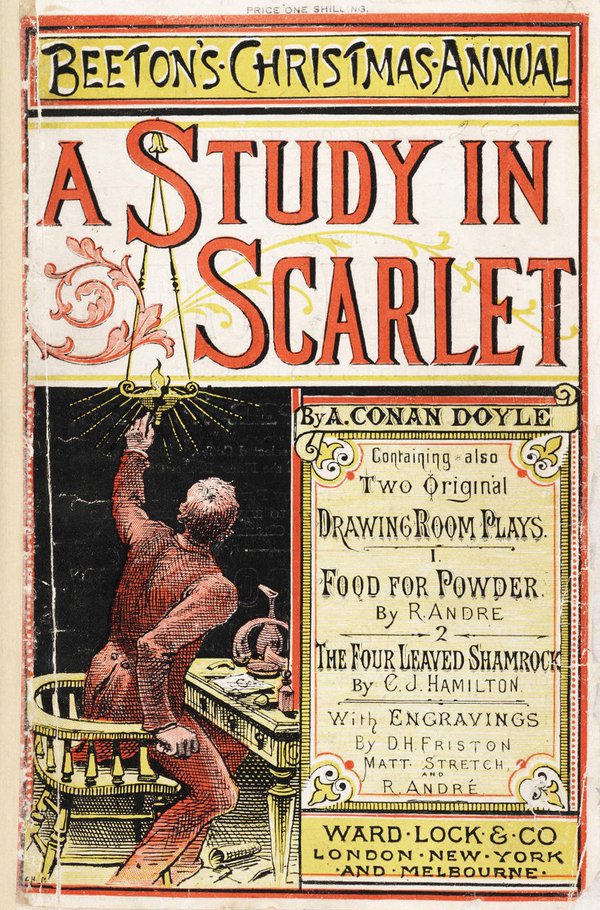

Christmas annuals have been around since the Victorian age, but it was in the 1920s that children's comic publishers began to monopolize the market. After all, they had a loyal readership, so sales were probably guarantee.

Over time the number of Christmas annuals began to rapidly increase, as more and more comics began to issue them to cash in on the Xmas market...

Even Britain's newspapers jumped on the Xmas bandwagon with their own annuals full of festive fun - though 'fun' might be pushing it a bit: long articles on 'how a newspaper is made' etc...

Up until the 1950s the children's Christmas annual was a somewhat middle class present: full colour printing was expensive, and not every child would be thrilled to receive a book from Santa instead of a cap gun or a tin of toffees.

But by the 1960s the market for Christmas annuals went through the roof, all thanks to one thing - television!

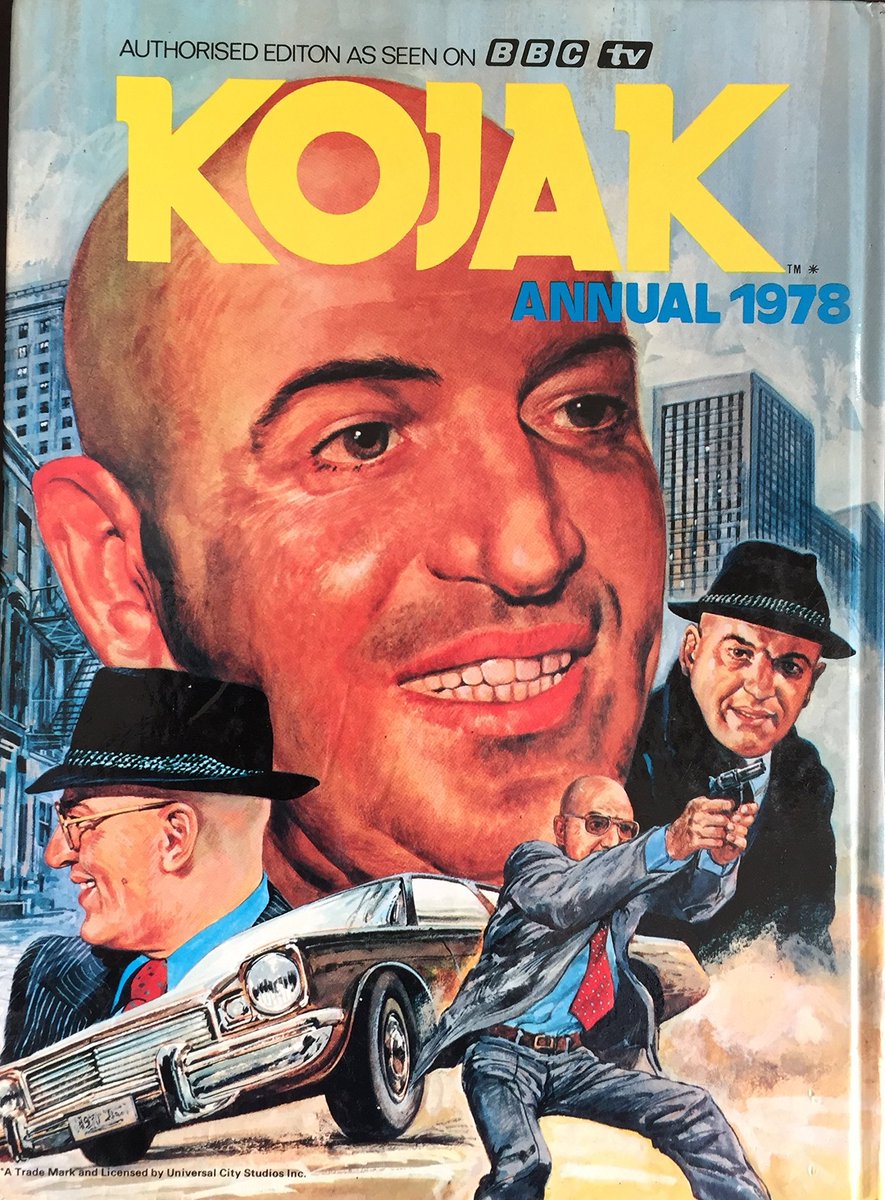

TV shows began to enter the Christmas annual market in a big way in the 1960s: whether they were shows aimed at children...

...or not! Basically if it was on the telly then there would be an annual at Christmas about it.

But were they any good?

But were they any good?

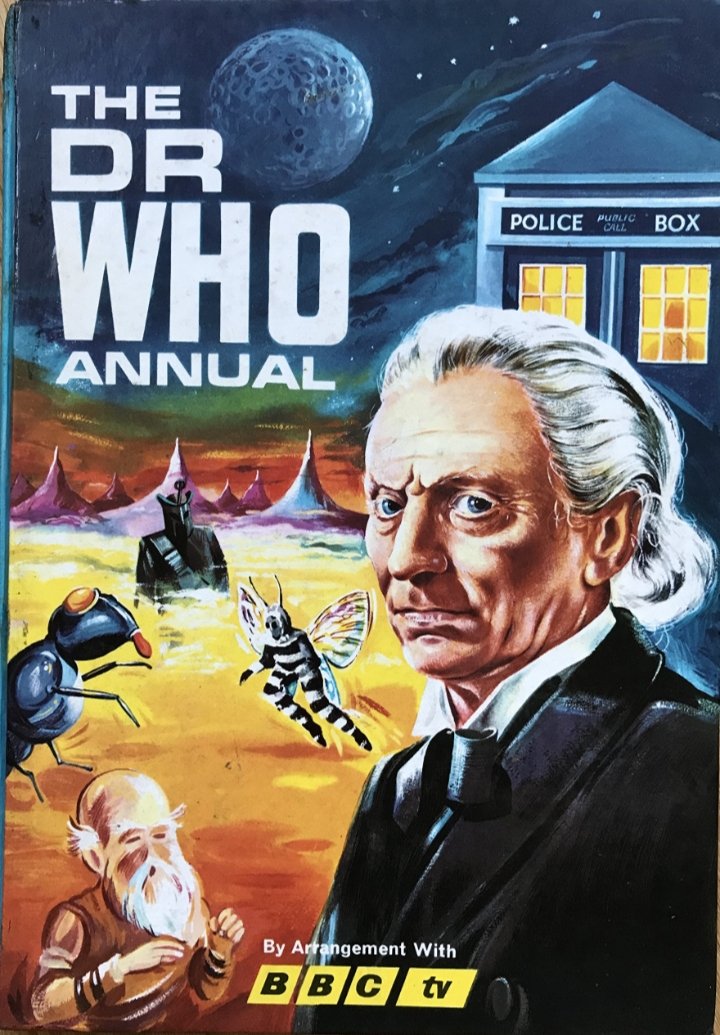

Well by the 1970s the format of the Christmas tv show annual was pretty much standardised. First, you got an exciting cover, with either some slightly wonky artwort or some ropey stock photography...

There would be lots of big photos to pad out the page count (you could doodle on these when you were bored on Boxing Day)...

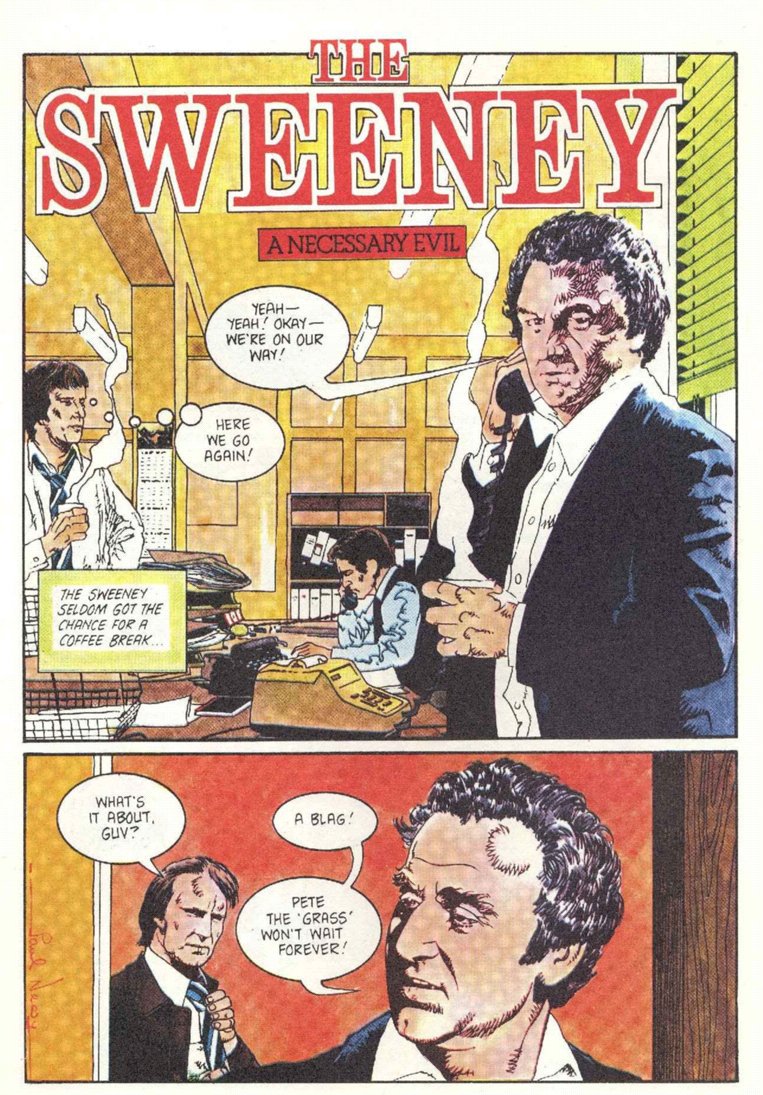

There would be some very dull stories featuring some truly terrible artwork, normally by an illustrator who hadn't seen the show...

Another fact file, another quiz, more photos, a colouring page ... on and on until they'd filled 100 pages as cheaply as they could.

That was the problem with TV annuals: they were licenced by companies that had nothing to do with the show and didn't seem to care!

That was the problem with TV annuals: they were licenced by companies that had nothing to do with the show and didn't seem to care!

For example: the Doctor Who Christmas annual artwork has long been a source of puzzlement to children. "Who's that weirdo on the cover?" kids would cry every 25th December. "Has he regenerated into the Child Catcher?" They'd then proceed to draw a nob on all the Daleks.

By a country mile the biggest annual publisher of all was Fleetway! You name it, they'd stick together a 100 page hardback on it and sell it for £2.99 at all good newsagents.

So if you wanted a good Christmas annual you were better off sticking to one based on a comic: the art would be decent and the stories would be interesting.

Despite a dip in the 1990s I'm pleased to say the Christmas annual market is still alive and well. Whether modern annuals are as collectable as those of yesteryear only time will tell!

More pulp stories another time...

More pulp stories another time...

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh