Why are there no secessionist tensions in Switzerland while they are strong in Belgium? A thread in maps.

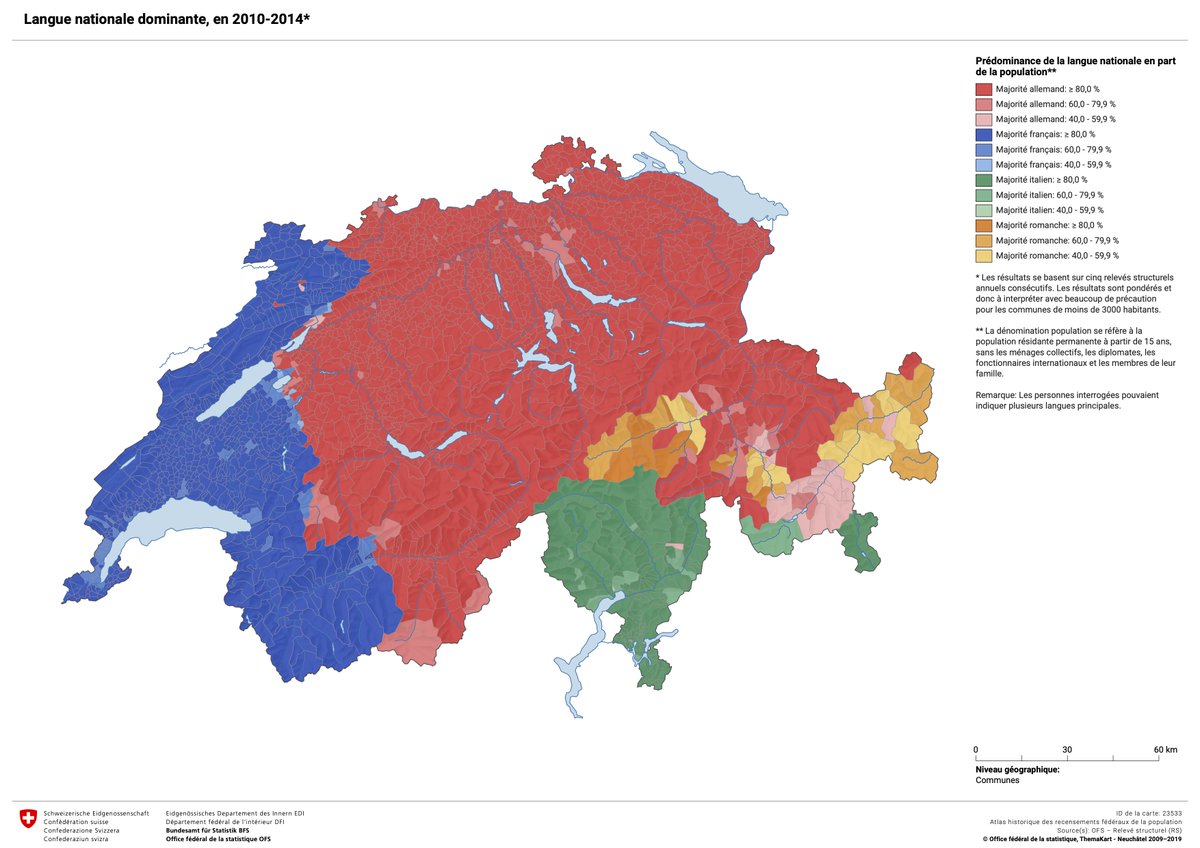

Here is a map of dominant languages in Switzerland and Belgium, namely French, German, Italian and Rumansh in Switzerland and French, Flemish and German in Belgium.

Now here is a map of average income by municipality in Belgium. As you can see, it doesn't track the language border absolutely perfectly, but there is nevertheless a fairly close correspondence between the two: Flanders is richer than Wallonia 3/

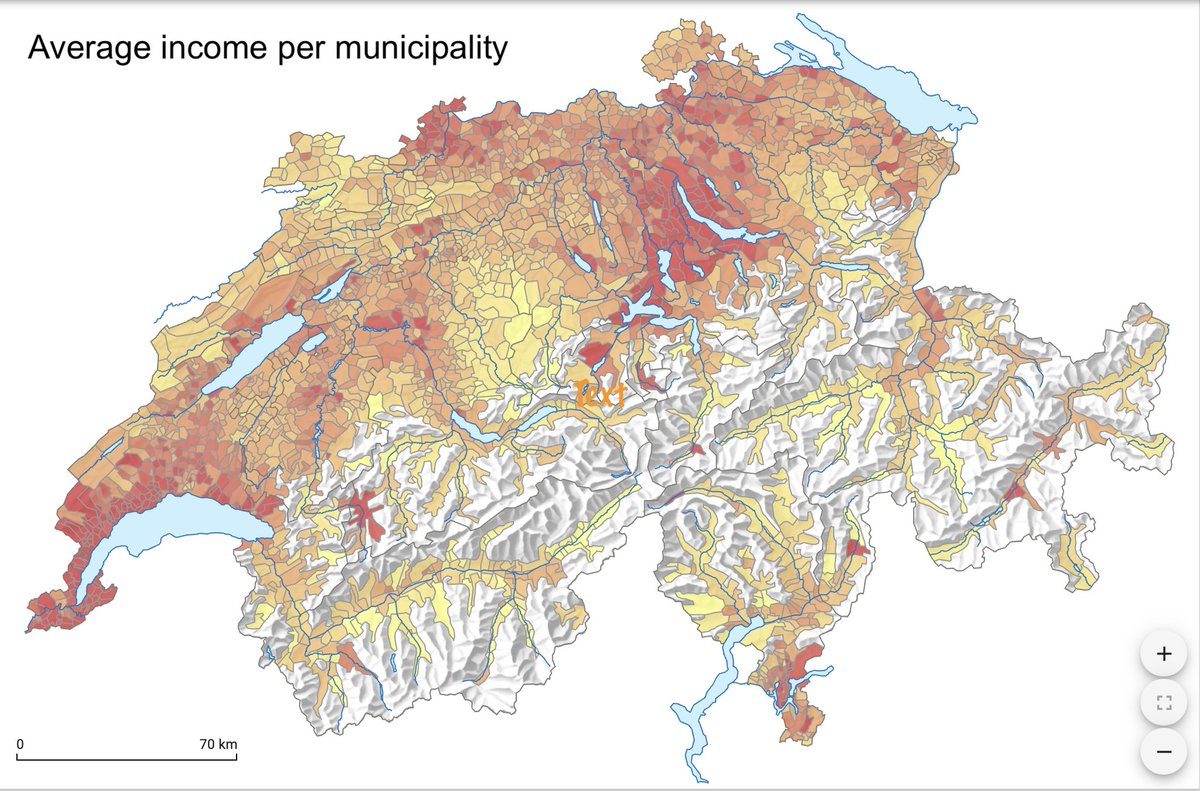

Now look at the equivalent income map for Switzerland: it doesn't track the language border at all. German-speaking Zurich is rich, but so is the French-speaking area around lake Geneva.

When economic and cultural or religious cleavages are aligned, they tend to reinforce each other and create opportunities for secessionism.

In Belgium, the narrative that French-speakers are a drain for Flanders can have traction because the economic and linguistic cleavage are *aligned*. In Switzerland these two cleavages are *not* aligned.

In contrast, Switzerland has traditionally had *cross-cutting* cleavages: here languages combined with religion: you can be French speaking and catholic (Jura), French-speaking protestant (GE, VD), German-speaking catholic (Uri), German speaking protestant (Bern)

Historically, this has meant that there was always something that *tied* members of a group to the other group. They had something in common.

Linguistic cleavages have remained very stable in Switzerland over time, but religion has declined a lot: here a map of religions in 2014 vs. 1900.

Yellow means no religion.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh