Today 19 December is anniversary of the 1562 Battle of Dreux during French Wars of Religion. A very bloody battle where French Catholic Royal Army defeated the Huguenots! Also a very interesting battle to study as it refutes many myths people have about warfare in renaissance.

Religious tensions between Catholics and Protestants had been going on for a while in France following many persecutions, riots and massacres, but it wasn't until this battle of Dreux that the two sides would meet in an open battle!

The Catholic Royal Army of France was led by the experienced commander Anne de Montmorency, a veteran of the Italian Wars who had fought in the legendary battles of Marignano (1516), Bicocca (1522) and Pavia (1525) decades ago.

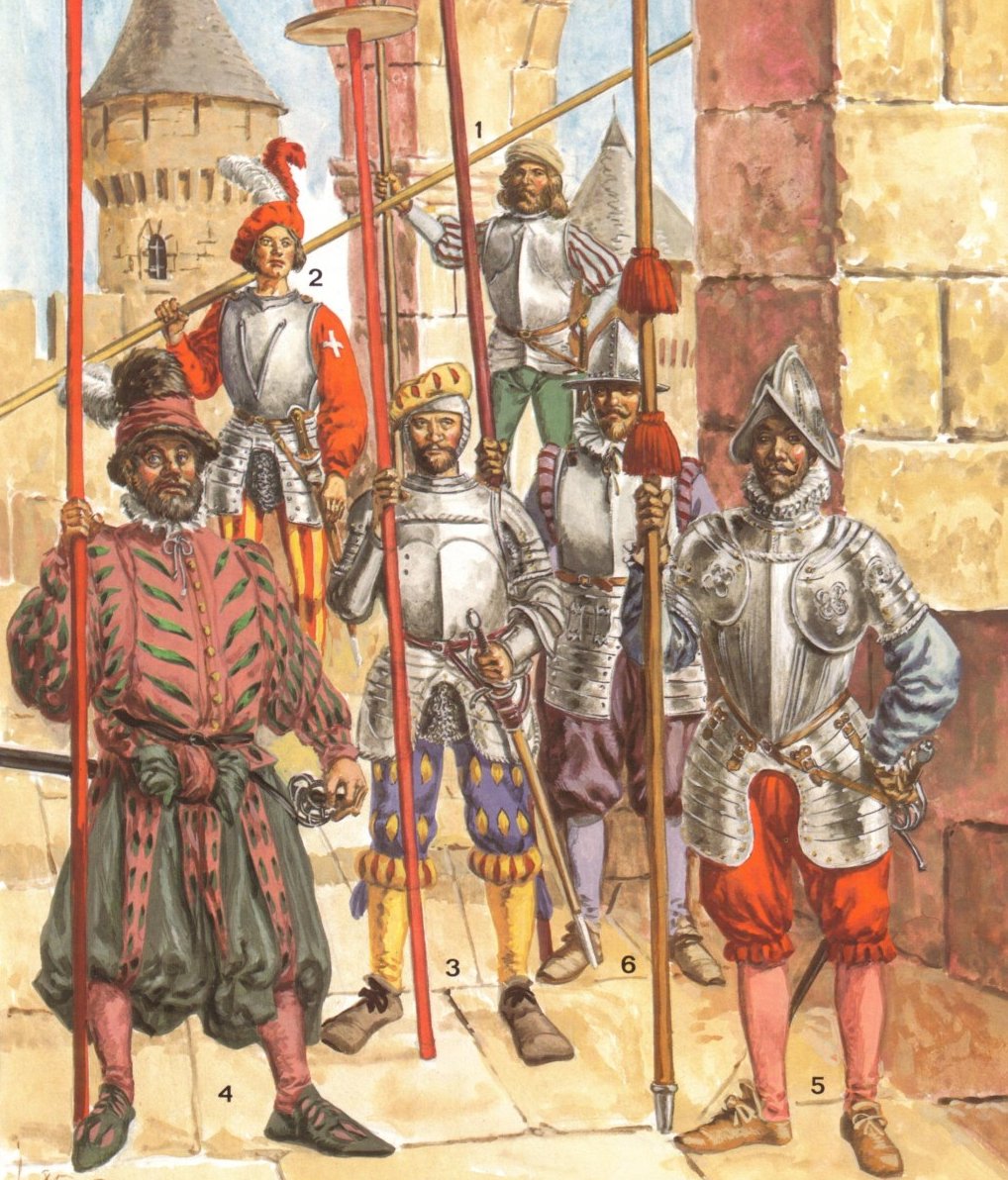

The army he commanded at Dreux in 1562 was not fundamentally different than the French armies during the Italian Wars. He relied on a large infantry force which included the famed Swiss mercenaries and Landsknechts, complimented by the French heavy cavalry and artillery.

The French still relied on the foreign Swiss and German mercenaries for infantry and the local French infantrymen they recruited from regions like Picardy and Brittany were in many cases just poorly trained peasant militias of inferior quality.

The Catholic French army numbered around 20000 men, and most of them were infantry and only around 2500-3000 were cavalry. On the other side the Protestants had inferior numbers of around 13000, but had a superior cavalry of 4500 which included German "reiter" mercenaries.

The German reiters were a novel military force. They were cavalrymen who used cheaper mass produced armor and were armed with pistols which they would fire from close range. They could also charge and engage in melee and were a versatile and affordable mercenary unit.

The problem of the Huguenot force was that their their commander Louis, Prince of Condé, was not a good military leader and very hesitant. In months prior to Dreux he had already wasted many great opportunities to put pressure on the Catholics and possibly defeat them.

Condé did not want this risky pitched battle at Dreux but was marching towards Normandy to meet up with Protestant allies the English after his siege of Paris failed due to his lack of initiative which gave Catholics precious time to assemble their huge army.

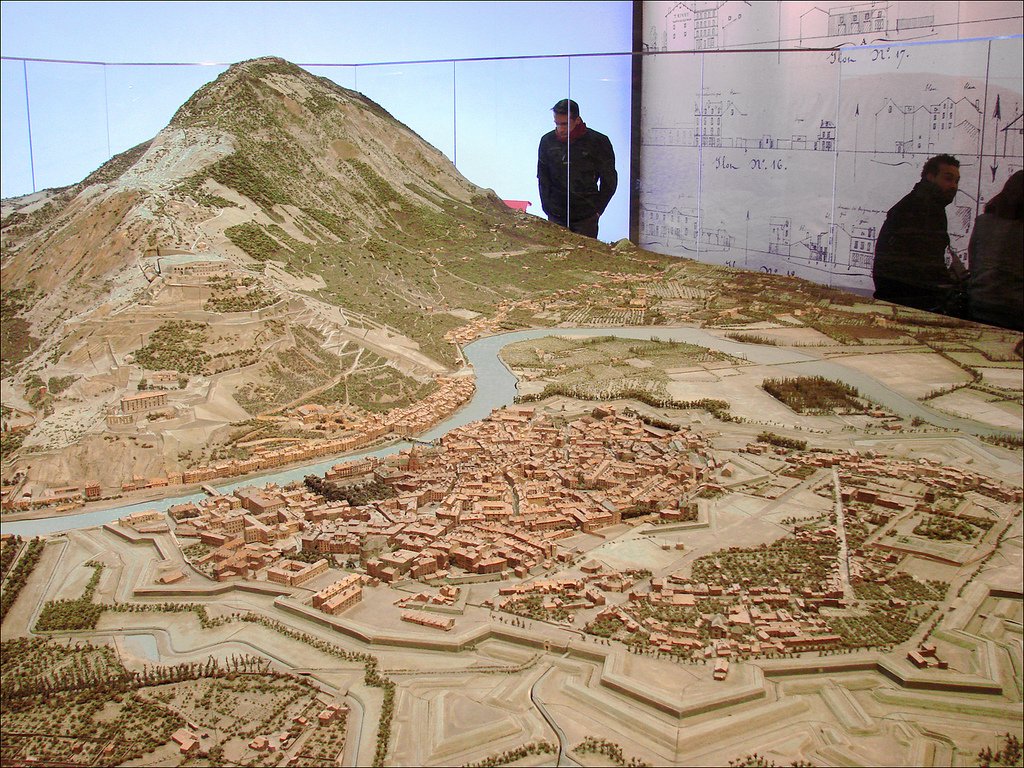

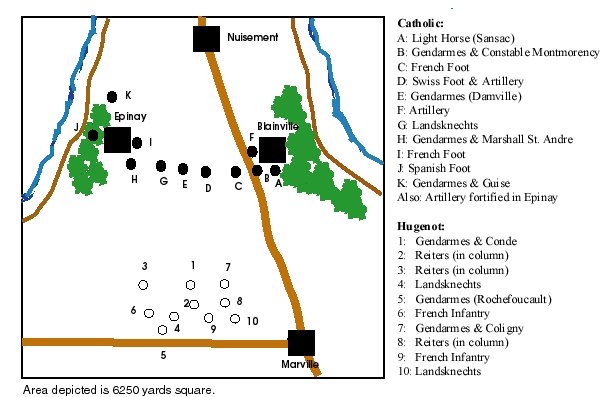

The Catholics were not eagerly aggressive either as they were aware of the inferiority of their cavalry. To make the best use of their imposing infantry, they chose a very wide formation and stretched their infantry between villages of Epinay and Blainville to avoid flanking.

The Protestants on the other hand opted for a "cavalry-centric" formation as they put all their imposing cavalry in front of infantry to prepare for a lethal charge at the enemy lines while using infantry only as back up.

The infantry of the Protestant side was not only numerically inferior but was also lacking in quality. Even though they did have a contingent of landsknecht mercenaries as well, the rest of their infantry was poorly armed and inexperienced.

Contrary to what people would expect from a fanatical religious war, neither of the two armies was particularly willing to shed blood that day. This was only the beginning of the civil war. The nobility on both sides had friends and relatives in the other side.

The two armies stared at each other for two hours before the Catholics decided to make the first moves with artillery. The Huguenot heavy cavalry countered it with a devastating charge against the left flank of the Catholic army with much success!

This Huguenot cavalry charge was commanded by Gaspard II de Coligny. With his heavy cavalry and reiters he destroyed and the Royalist cavalry on the left flank and French infantry, while also inflicting large casualties on the Swiss and pushed them to the center.

This cavalry charge shows well that the common perception of "infantry revolution" in late middle ages and renaissance is often massively exaggerated and that heavy cavalry was still a lethal force and decisive in battles even as late as this battle of Dreux in 1562.

Thus contrary to this popular myth a numerically inferior Protestant army that had twice less infantry than the Catholic was on the verge of victory thanks to their cavalry alone. However they made crucial mistakes and did not exploit their success!

The Huguenot cavalry managed to capture the Catholic leader Montmorency and took him in the custody, but drunk on their success when they advanced to the enemy camp behind the Catholic army they started looting it instead of capitalizing on their charge and rejoining the battle.

Condé tried to finish off the Swiss in the center with his infantry and remainder of his cavalry, however the famed Swiss mercenaries proved their worth once again and managed to stand their ground against multiple cavalry charges and routed enemy Landsknecht infantry as well.

If at that point the Coligny's Huguenot cavalry had rejoined the battle and flanked the Catholics from behind, it could have been all over from the Royal army, but they were still busy looting the enemy camp. The battle swung into Catholic favor!

On the right flank the Landsknechts on the Royal side routed the inexperienced Huguenot infantry while Condé's cavalry was overwhelmed by the numerically larger force in the center and forced to retreat with Condé himself being captured.

This led to a weird situation where commanders on both sides were now captured by the enemy forces! Coligny's cavalry finally rejoined the battle in one final attempt to reverse the tide, but the massed Catholic infantry was too numerous for them to overcome and they retreated.

This is how the battle of Dreux was won by the Catholics. It was a very brutal battle even for the standards of the age as around 9000 men were dead altogether, both sides sustaining a similar number of casualties.

Even though they won the battle, the Catholics lost a lot of their important nobility as their cavalry sustained a lot of casualties. Meanwhile the Huguenot casualties were almost entirely infantry as cavalry was able to retreat in good order.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh