🧵 Tomorrow night is ‘Shab-e Yaldā,’ the longest and darkest night of the year!

Iranic peoples spend the night in celebration - but why is the winter solstice important to them? (1/8)

Iranic peoples spend the night in celebration - but why is the winter solstice important to them? (1/8)

Also known as Shab-e Chilla, Yaldā falls on December 21st, which is the end of the Iranian month ‘Āzar.’

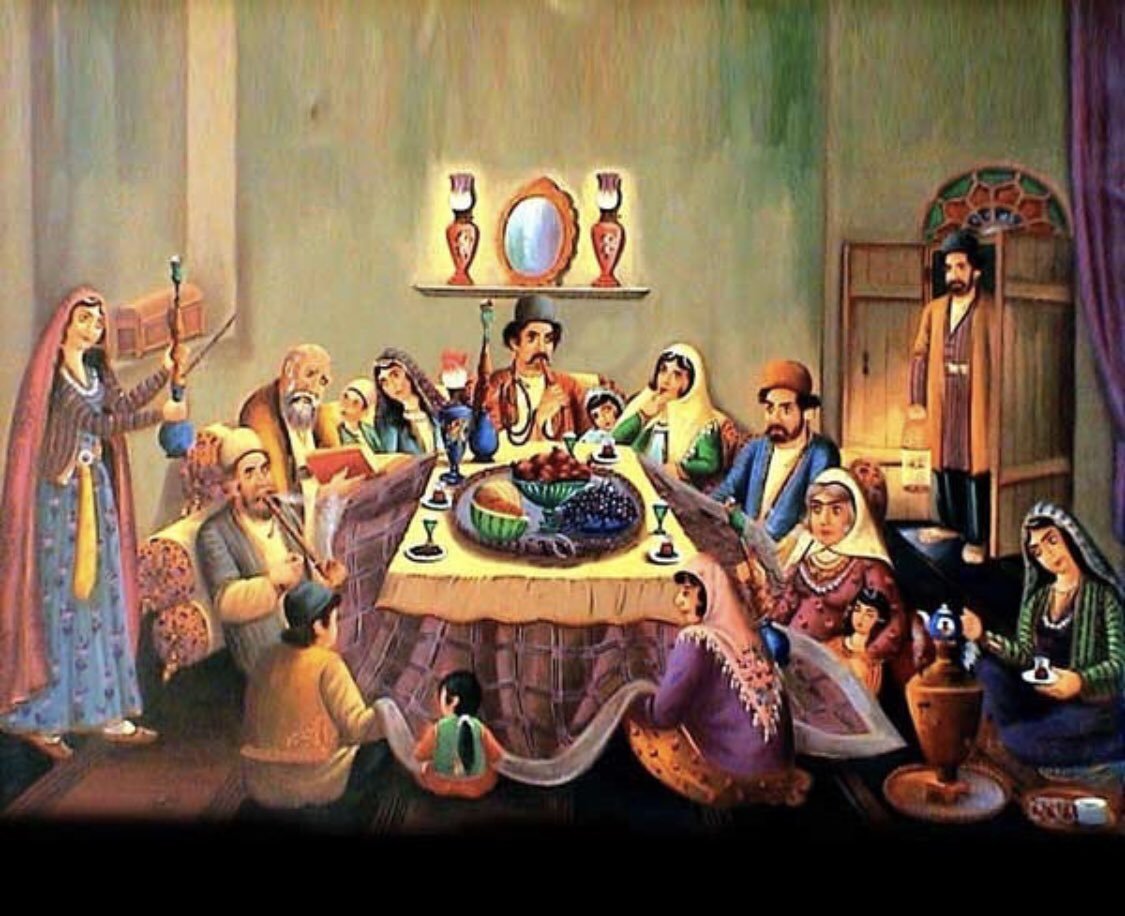

Iranic peoples get together and stay up all eating pomegranates and other foods while sitting under a heated table called a ‘kursī.’ (2/8)

Iranic peoples get together and stay up all eating pomegranates and other foods while sitting under a heated table called a ‘kursī.’ (2/8)

Persian readers go to Hāfez’s dīwān for divination (fāl-e hāfez):

Each person present chooses a Hāfez poem at random, then the poem is read aloud and the others predict what life has in store for that person. (3/8)

Each person present chooses a Hāfez poem at random, then the poem is read aloud and the others predict what life has in store for that person. (3/8)

Yaldā marks the first forty nights of winter, hence its first name Shab-e Chilla, meaning ‘night of the forty[-day period].’

Forty-days intervals are significant in Iranic culture: Sufis go into forty-day seclusions and relatives visit the deceased forty days after burial. (4/8)

Forty-days intervals are significant in Iranic culture: Sufis go into forty-day seclusions and relatives visit the deceased forty days after burial. (4/8)

Like Nawroz, Chilla has its roots in Zoroastrianism:

Zoroastrians believed that the Ahriman (the evil spirit) was most active during the night, so they would stay up with company during the year's longest night to stay safe, eating what remained of that year’s harvest. (5/8)

Zoroastrians believed that the Ahriman (the evil spirit) was most active during the night, so they would stay up with company during the year's longest night to stay safe, eating what remained of that year’s harvest. (5/8)

Chilla took its second name ‘Yaldā’ in the first century when Christians fleeing persecution settled in Persia.

In Syriac, Christmas is ‘Yaldā,’ meaning birth or nativity (cognate to the Arabic w-l-d). Due to its proximity, Shab-e Chilla also took on the name Yaldā. (6/8)

In Syriac, Christmas is ‘Yaldā,’ meaning birth or nativity (cognate to the Arabic w-l-d). Due to its proximity, Shab-e Chilla also took on the name Yaldā. (6/8)

If you celebrate Yaldā, we’d love to see it!

Quote this tweet with a photo and let us know what city, country, or ethnic group you hail from.

We'll choose our favorites and post them on our Instagram story! Find us here: instagram.com/persianpoetics (7/8)

Quote this tweet with a photo and let us know what city, country, or ethnic group you hail from.

We'll choose our favorites and post them on our Instagram story! Find us here: instagram.com/persianpoetics (7/8)

If you're interested in Persian poetry and culture, do give us a follow and support us on Patreon (patreon.com/persianpoetics).

Also be sure to see our upcoming course: persianpoetics.com/poetess

(8/8)

Also be sure to see our upcoming course: persianpoetics.com/poetess

(8/8)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh