The Quranic Ayah

transcendent between disputants

🧵

transcendent between disputants

🧵

Some people asked me to comment on a particular use of a particular ayah by a particular group to support their particular doctrine. And I intend to do that, iA. But I feel that taking a few steps back is helpful before diving in.

Suppose Group A say “This ayah proves our point!” – this is obviously insufficient if there are other ayat which are relevant, especially if some go against that point.

On many important issues, there are ayat which can plausibly be used by both sides of a debate. Someone with no horse in the race (like a secular academic) might say “The Quran is ambivalent” or even “confused” on the issue.

Groups A and B, however, each have to believe that all the ayat are actually on their side. Crudely, A says to B: “If you think any ayah supports you, you’ve failed to understand it!”

A more mature approach is to acknowledge that some ayat at least *appear* to support B; but when you interpret them more subtly, they don’t. Especially when put alongside the clearer evidences for A.

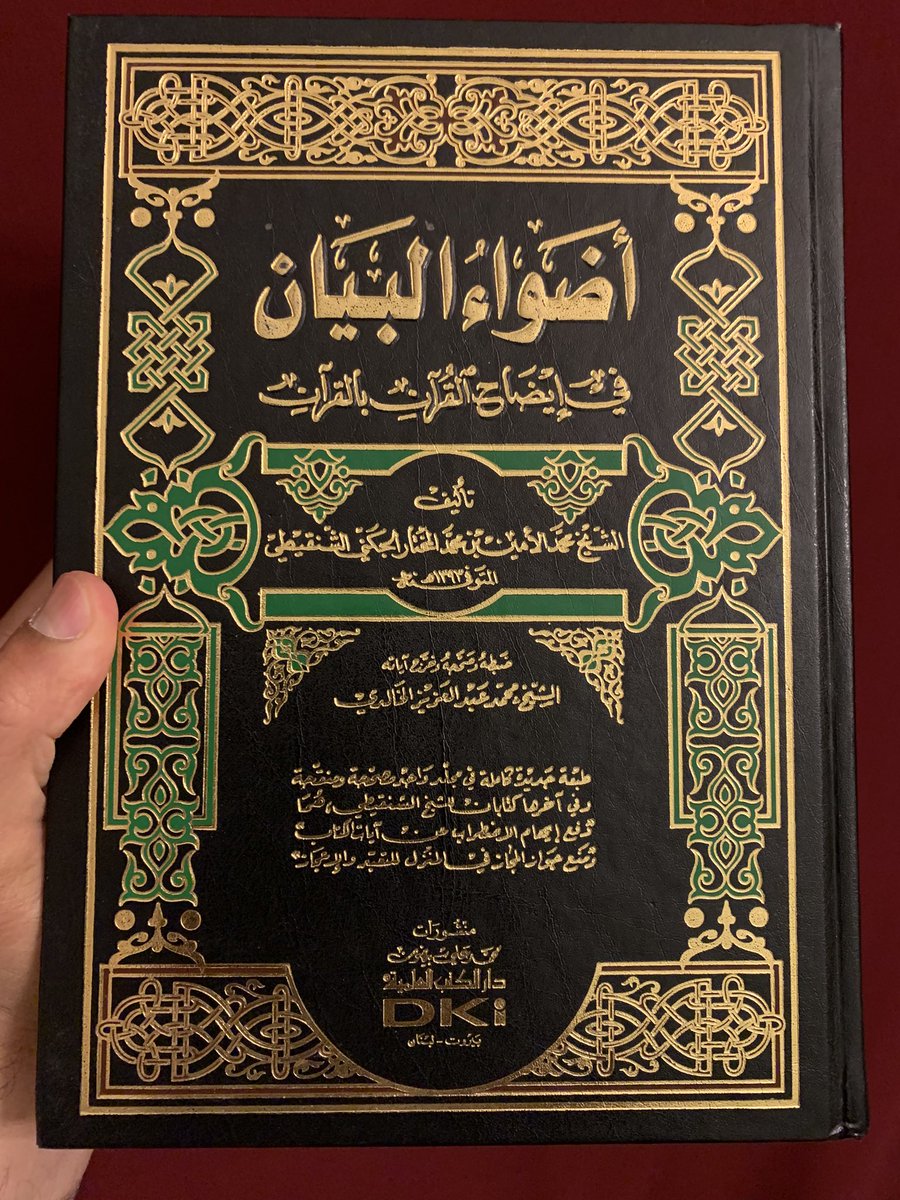

What I just described is the basis for the Mutashābih al-Qur’ān genre (pioneered by the Muʿtazilah). The point is to show that your own group is relying on the clear-cut (muḥkam) verses, and your opponent is either fooled by the phrasing, or stretching the meaning unacceptably.

This mature attitude doesn’t mean accepting that the Qur’an is “confused” but certainly acknowledges that there’s a challenge involved in pondering it and being guided aright. Imam Rāzī expresses this beautifully in the context of the free will debate:

https://twitter.com/tafsirdoctor/status/1107716143756861440?s=20

So, Group A should accept that Allah ﷻ revealed some ayat with words that challenge what Group A believe. And they have to be OK with that. The first level is to say “That is to test who will interpret these ‘difficult’ ayat correctly.”

A higher level, rarely observed in the wild, is to say: “There is something in that particular wording that would have been lost if it were worded more directly in line with what we believe is the right interpretation of it.”

Following from both points: “The ambiguity isn’t just a test, but points to something about the issue itself. Neither the word choice nor the contrasting ayat happened by accident. Must ponder harder.”

These 2 principles which guide a lot of my own pondering these days. You may not find them in the books of qawāʿid, but that doesn’t mean they’re not valid. Just ponder on what I’ve laid out for you above.

–“The ẓāhir is always intended on some level”

– “Ambiguity is meaningful”

–“The ẓāhir is always intended on some level”

– “Ambiguity is meaningful”

Finally, a note on polemical use of ayat. Pondering is based on vulnerability: you have to be ready to be wrong, hear better ideas, think again. In polemics, you must always be right. That’s the death of pondering.

That’s why we must go on a journey before I tell you about that particular group’s particular use of the particular ayah. Will you be ready to hear that they actually have a point? Maybe not a foolproof one, but a point nonetheless?

As for that group: are they ready to analyse what kind of denotation (dalālah) their reading is based on? Will they be honest about its epistemic status: is it really as certain as you have to boast during disputation?

Come, let us ponder together!

This journey requires maturity and humility.

This journey requires maturity and humility.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh