The Quran has a written form and recited forms. Its written form remained more or less unchanged. But the recited forms were sometimes at odds with what is written in the text.

A thread on what scribes did to alleviate these conflicts, in early Quranic manuscripts.🧵

A thread on what scribes did to alleviate these conflicts, in early Quranic manuscripts.🧵

Conflicts between the written and the recited should be familiar to those who know the Hebrew Bible, which shows a peculiar interplay between the standard written text (ktiv), and its recitation (qre) which are not infrequently at odds with one another.

Such differences are marked with marginal ktiv-qre notes. Notes that point out that the word written is to be recited differently.

In Josh 13:16 the written באדם "at Adam", has a ktiv-qre note in the margin to point out it should be read מאדם "from Adam".

In Josh 13:16 the written באדם "at Adam", has a ktiv-qre note in the margin to point out it should be read מאדם "from Adam".

The has many such notes, some quite exotic. There are, for example, cases where the recited form adds a whole word absent in the text (which leaves disembodied vowels in the text), e.g. 2 Sam 8:3 spelled just בנהר "at the river" but recited binhar pəråṯ "at the Euphrates river".

Interventions in the consonantal skeleton by the Quranic reading traditions are not quite so drastic, and as such a deeply developed marginal note system never arose. Yet, vocalised manuscripts did need to find a way to deal with it. So how did they do it? Let's take a look.

Q18:38 لكنا "but as for me" has as most straightforward reading lākinnā. And the red vocalisation marks that.

But the majority of canonical readers read lākinna, which is marked as a secondary greeb reading by finishing the nūn with the curve of the nūn on the denticle.

But the majority of canonical readers read lākinna, which is marked as a secondary greeb reading by finishing the nūn with the curve of the nūn on the denticle.

A similar strategy is found with Q2:259 لم يتسنه which many readers read lam yatasannah (marked ni red), but some drop the final hāʾ in connected speech, lam yatasanna. This is once again marked with a green finishing of the nūn. The hāʾ also carries a green cancellation mark.

Likewise, the reading of Q6:90 اقتده as iqtadi instead of iqtadih, is marked with a cancellation sign over the hāʾ. This time the previous letter does not need to be modified, dāl already has its final form!

Most readers read Q19:19 لاهب in the natural way as the rasm suggests li-ʾahaba 'so that I may give'. But ʾAbū ʿAmr and Nāfiʿ read li-yahaba 'so that he may give'. This is marked in here by adding a red medial yāʾ between the lām-ʾalif and the hāʾ! li-ʾahaba marked in Green.

Another case where the primary reading adds to the rasm and the secondary reading does not. Primary (red) reads Q40:32 as at-tanādī, adding an extra red yāʾ to the text. Green marks at-tanādi.

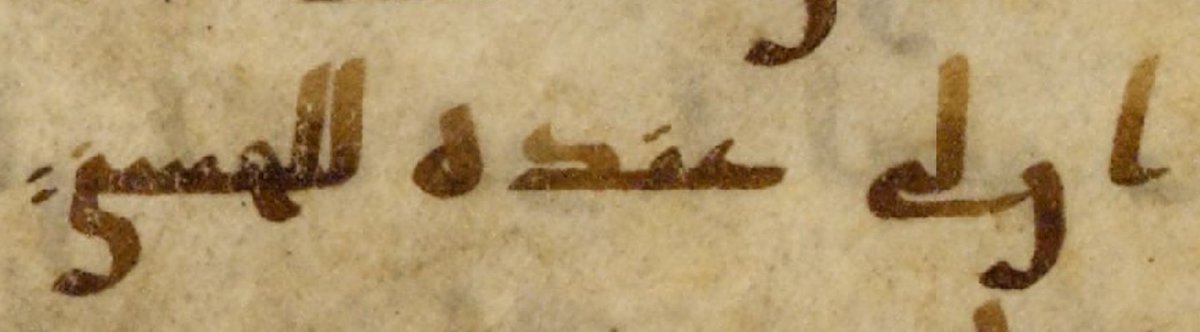

But sometimes the written text disagrees with ALL reading traditions. Q18:10 hayyiʾ, is consistently spelled هيا in early Quranic manuscripts. But all read it hayyiʾ, where one expects a spelling هيى.

Scribe cancelled out the ʾalif with a dash, and added final yāʾ to the 1st yāʾ!

Scribe cancelled out the ʾalif with a dash, and added final yāʾ to the 1st yāʾ!

Sometimes, such interventions in the consonantal text are used to mark readings that are not strictly in agreement with the rasm.

Q3:97 ايت بينات has its tāʾs and ʾalif crossed out in green, and hāʾs added in order to spell ʾāyatun bayyinatun. a well-known non-canonical variant.

Q3:97 ايت بينات has its tāʾs and ʾalif crossed out in green, and hāʾs added in order to spell ʾāyatun bayyinatun. a well-known non-canonical variant.

I find these kinds of original solutions to writing a reading that doesn't fully agree with the standard written text incredibly interesting and fun to see.

The system used seems quite formalized, although visually it looks a little sloppier than the Hebrew ktiv-qre system.

The system used seems quite formalized, although visually it looks a little sloppier than the Hebrew ktiv-qre system.

If you enjoyed this thread, and would like to support me and get exclusive access to my work-in-progress critical edition of the Quran, consider becoming a patron on patreon.com/PhDniX/!

You can also always buy me a coffee as a token of appreciation.

ko-fi.com/phdnix

You can also always buy me a coffee as a token of appreciation.

ko-fi.com/phdnix

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh