Are you confused about #COVID?

How do you know when you have it?

Who can get a test?

When to use a RAT?

When to call a doctor?

You're not alone.

We @UofTFamilyMed @OntarioCollege have pulled together answers to common COVID Q's

dfcm.utoronto.ca/confused-about…

Here's a rundown 🧵

How do you know when you have it?

Who can get a test?

When to use a RAT?

When to call a doctor?

You're not alone.

We @UofTFamilyMed @OntarioCollege have pulled together answers to common COVID Q's

dfcm.utoronto.ca/confused-about…

Here's a rundown 🧵

1. How do you know you have COVID?

Bottom line: If you have symptoms, assume you have COVID

(Most people don't qualify for a PCR test)

dfcm.utoronto.ca/sites/default/…

Bottom line: If you have symptoms, assume you have COVID

(Most people don't qualify for a PCR test)

dfcm.utoronto.ca/sites/default/…

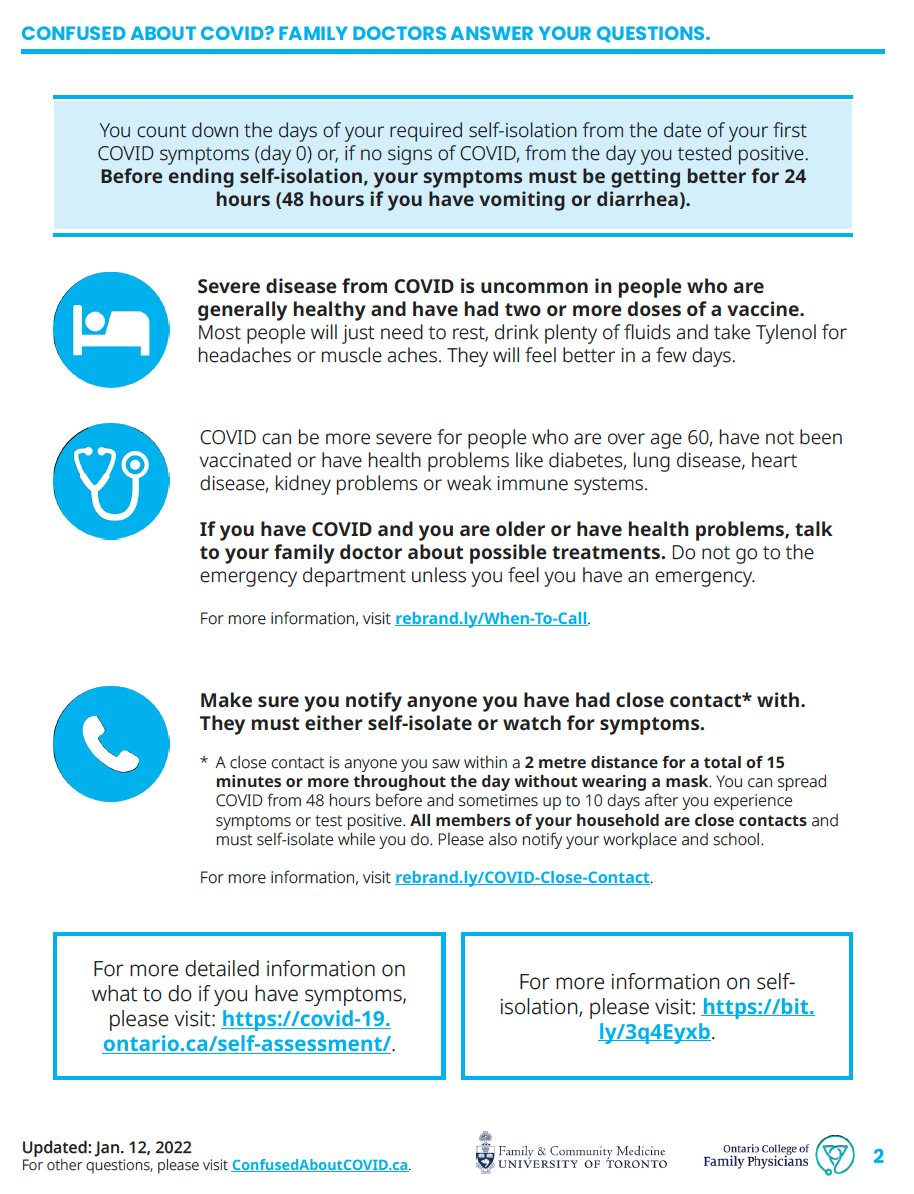

2. When should I call my doctor?

i) if you have a pre-existing condition that needs attention

ii) if you might quality for treatment (e.g. very weak immune system, over 60, over 50 + certain medical conditions)

iii) you really are not feeling well!

dfcm.utoronto.ca/sites/default/…

i) if you have a pre-existing condition that needs attention

ii) if you might quality for treatment (e.g. very weak immune system, over 60, over 50 + certain medical conditions)

iii) you really are not feeling well!

dfcm.utoronto.ca/sites/default/…

Some specific advice in there too about what to do if you are caring for a child with COVID and when you should be worried

3. Do I need a COVID PCR test?

Most people aren't eligible for one in Ontario

These tests are now reserved for high-risk settings and individuals at high-risk of more severe illness 👇🏽

dfcm.utoronto.ca/sites/default/…

Most people aren't eligible for one in Ontario

These tests are now reserved for high-risk settings and individuals at high-risk of more severe illness 👇🏽

dfcm.utoronto.ca/sites/default/…

4. When do I use a RAT?

There are 3 main recommended uses:

1. Testing when you have symptoms

2. As part of an organized screening program

3. Testing to return to work

(A 4th use, one-time testing before gathering, is no longer really recommended)

dfcm.utoronto.ca/sites/default/…

There are 3 main recommended uses:

1. Testing when you have symptoms

2. As part of an organized screening program

3. Testing to return to work

(A 4th use, one-time testing before gathering, is no longer really recommended)

dfcm.utoronto.ca/sites/default/…

5. What should I do if I've been exposed to COVID?

(This one was the hardest to write b/c so confusing!)

Bottom line:

self-isolate if

-you have symptoms

-you live with the person with COVID

-you have <2 vaccines or a very weak immune system

dfcm.utoronto.ca/sites/default/…

(This one was the hardest to write b/c so confusing!)

Bottom line:

self-isolate if

-you have symptoms

-you live with the person with COVID

-you have <2 vaccines or a very weak immune system

dfcm.utoronto.ca/sites/default/…

Some people won't have to self-isolate but should still be careful!

(and guidance is different if you work in a high-risk setting!)

(and guidance is different if you work in a high-risk setting!)

6. How do I keep safe during Omicron?

Vaccination, vaccination, vaccination—whether that's your 1st, 2nd, 3rd, or 4th dose!

Most people with 2+ vaccines & healthy immune systems will be able to recover at home without seeing a doctor

dfcm.utoronto.ca/sites/default/…

Vaccination, vaccination, vaccination—whether that's your 1st, 2nd, 3rd, or 4th dose!

Most people with 2+ vaccines & healthy immune systems will be able to recover at home without seeing a doctor

dfcm.utoronto.ca/sites/default/…

We will do our best to keep these resources up-to-date with evolving guidance

We will also be translating them into a few commonly spoken languages

And we would love your feedback. Did we get something wrong? What questions do you have that we should answer? Replies welcome!

We will also be translating them into a few commonly spoken languages

And we would love your feedback. Did we get something wrong? What questions do you have that we should answer? Replies welcome!

Grateful to work on these alongside @docdanielle and our terrific comms team @UofTFamilyMed

Thank you to the many who provided edits including @NoahIvers @AndreaChittle @OCFP_President @NoorRamji @DrJPeranson + others!

Thank you to the many who provided edits including @NoahIvers @AndreaChittle @OCFP_President @NoorRamji @DrJPeranson + others!

Tagging some friends, colleagues, and sci comm heroes to help share these @RitikaGoelTO @DanyaalRaza @OnyeActiveMD @AndrewDPinto @drandrewb @DocMCohen @heysciencesam @DrKateJMiller @kgrindrod @PharmacistMama @MPaiMD @nilikm @jkwan_md @MoriartyLab @KrishanaSankar @DrJeffKwong

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh