Over the last two months I've read dozens of studies about gas stoves and indoor air quality.

I also installed monitors in our home and ran my own tests.

Here's a thread on what I learned 🧵 #energytwitter

I also installed monitors in our home and ran my own tests.

Here's a thread on what I learned 🧵 #energytwitter

First, I should admit that I was skeptical about the panic over gas stoves at first.

As a climate hawk, I was focused on the emissions.

Gas stoves are responsible for 0.12% of emissions in America. I felt like we should focus on the bigger stuff (furnaces and water heaters).

As a climate hawk, I was focused on the emissions.

Gas stoves are responsible for 0.12% of emissions in America. I felt like we should focus on the bigger stuff (furnaces and water heaters).

But then I learned about the negative health impacts of gas stoves.

Researchers have been studying this stuff for decades. And every year, it becomes more clear:

Gas stoves produce unsafe levels of nitrogen dioxide (NO2). And that causes respiratory illnesses like asthma.

Researchers have been studying this stuff for decades. And every year, it becomes more clear:

Gas stoves produce unsafe levels of nitrogen dioxide (NO2). And that causes respiratory illnesses like asthma.

In Sept, @WHO released their latest guidelines on indoor air pollution.

They recommended no building should have higher than 5.3ppb of NO2 on average throughout the year.

So I set up air quality monitors in my house to see if we passed the test.

They recommended no building should have higher than 5.3ppb of NO2 on average throughout the year.

So I set up air quality monitors in my house to see if we passed the test.

Here's a chart showing the average level of NO2 throughout December.

The dotted line is the daily average. The top line is the peak concentration.

Our daily average hovered around 2x the WHO guidelines.

The dotted line is the daily average. The top line is the peak concentration.

Our daily average hovered around 2x the WHO guidelines.

Can you guess which day we went out of the town and didn't use our gas stove, furnace or water heater?

Yup, it was the day that NO2 levels plummeted.

Yup, it was the day that NO2 levels plummeted.

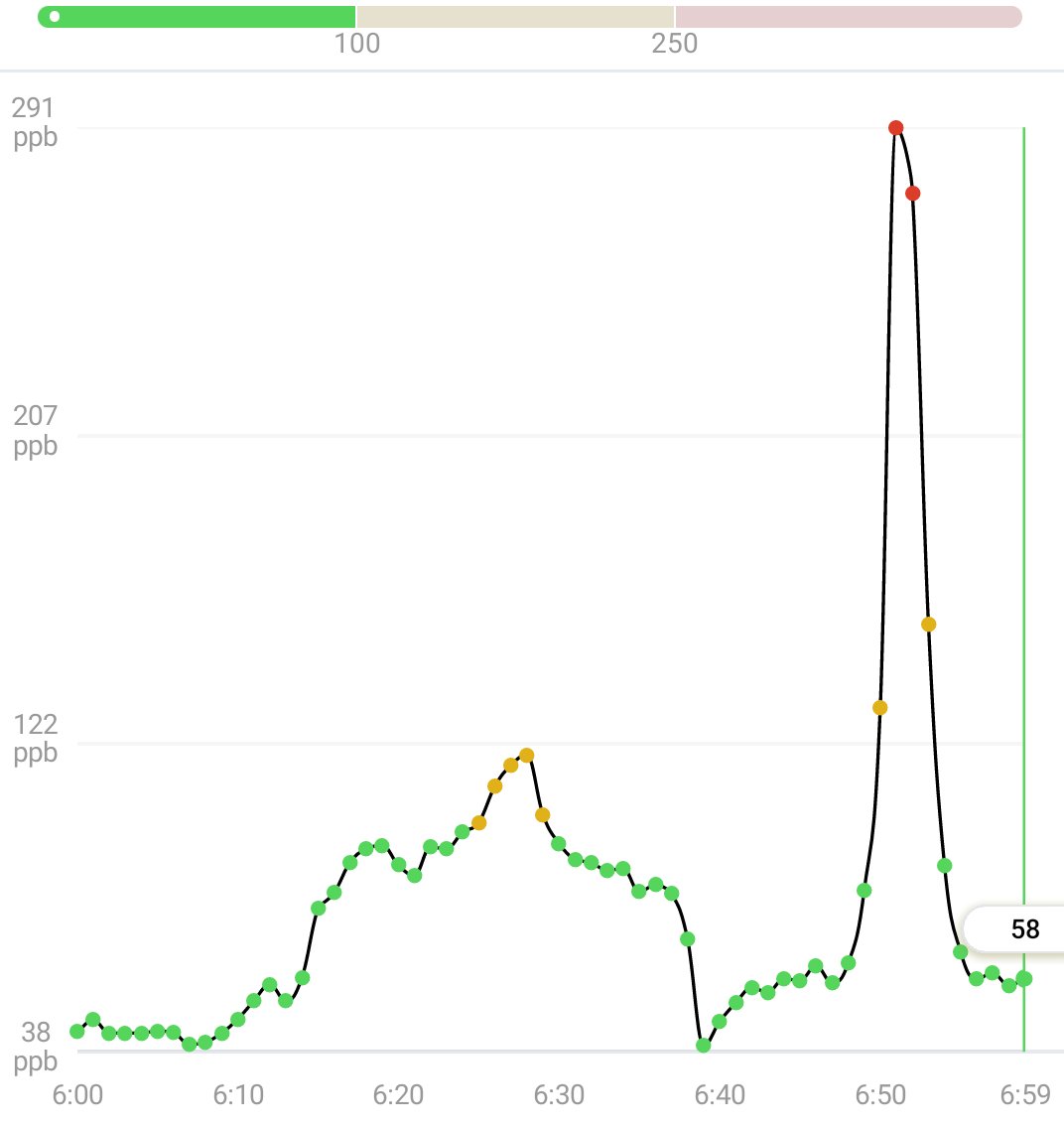

Here's what happened every night when we used our stove or oven.

291ppb of peak concentration is... not good.

And that's what it looked like whenever we made dinner.

The only exception: the nights we got takeout and didn't use the gas stove.

291ppb of peak concentration is... not good.

And that's what it looked like whenever we made dinner.

The only exception: the nights we got takeout and didn't use the gas stove.

I asked @jlashk, an environmental epidemiologist to take a look at the data.

He said, "I would say you've got a pretty big NO2 problem."

Not exactly what you want to hear from someone who studies this stuff for a living.

He said, "I would say you've got a pretty big NO2 problem."

Not exactly what you want to hear from someone who studies this stuff for a living.

NO2 is especially bad for children.

The first meta-analysis on this topic was published in 1992.

It found that for every 16ppb increase in NO2 levels — comparable to the increase resulting from exposure to a gas stove — the odds of respiratory illness in children go up by 20%.

The first meta-analysis on this topic was published in 1992.

It found that for every 16ppb increase in NO2 levels — comparable to the increase resulting from exposure to a gas stove — the odds of respiratory illness in children go up by 20%.

In 2013 another meta-analysis on the topic came out.

This time the authors concluded, “Children living in a home with gas cooking have a 42% increased risk of having current asthma.”

This time the authors concluded, “Children living in a home with gas cooking have a 42% increased risk of having current asthma.”

And think about that for a second.

We've known that gas stoves cause asthma and other respiratory illnesses for 30 years.

Yet, in that same period millions of homes have been built with gas hookups.

We've known that gas stoves cause asthma and other respiratory illnesses for 30 years.

Yet, in that same period millions of homes have been built with gas hookups.

The fact that we still allow these things in new construction is crazy.

Most building codes have nothing to say about gas appliances or NO2.

This is a failure of the @EPA and most state and city governments in America.

Most building codes have nothing to say about gas appliances or NO2.

This is a failure of the @EPA and most state and city governments in America.

Like I said, I was skeptical about all this at first. But in study after study that I read, the data showed the same thing.

Gas stoves aren't safe.

Gas stoves aren't safe.

You can read more about what I learned and find links to all the sources of data here - carbonswitch.co/how-bad-is-my-…

Shoutout to @jlashk for his research on this topic and helping me make sense of my indoor air quality data.

Thanks to @MothersOutFront @RockyMtnInst and @SierraClub for their advocacy on this issue.

And thanks to @drvolts @rebleber @jeffbradynews for their reporting on this.

Thanks to @MothersOutFront @RockyMtnInst and @SierraClub for their advocacy on this issue.

And thanks to @drvolts @rebleber @jeffbradynews for their reporting on this.

Update: lots of people asking about ventilation.

Unfortunately range hoods don't reduce NO2 (see peer-reviewed research below).

In other words, for the context of this research it was irrelevant.

More here -

Unfortunately range hoods don't reduce NO2 (see peer-reviewed research below).

In other words, for the context of this research it was irrelevant.

More here -

https://twitter.com/curious_founder/status/1482013311034142722?t=ws04_-0jRXVtcp-vuWcn9g&s=19

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh