This recent study by @C_Dorninger et al. shows that economic growth in high-income nations occurs at the expense of poorer countries.

THREAD

THREAD

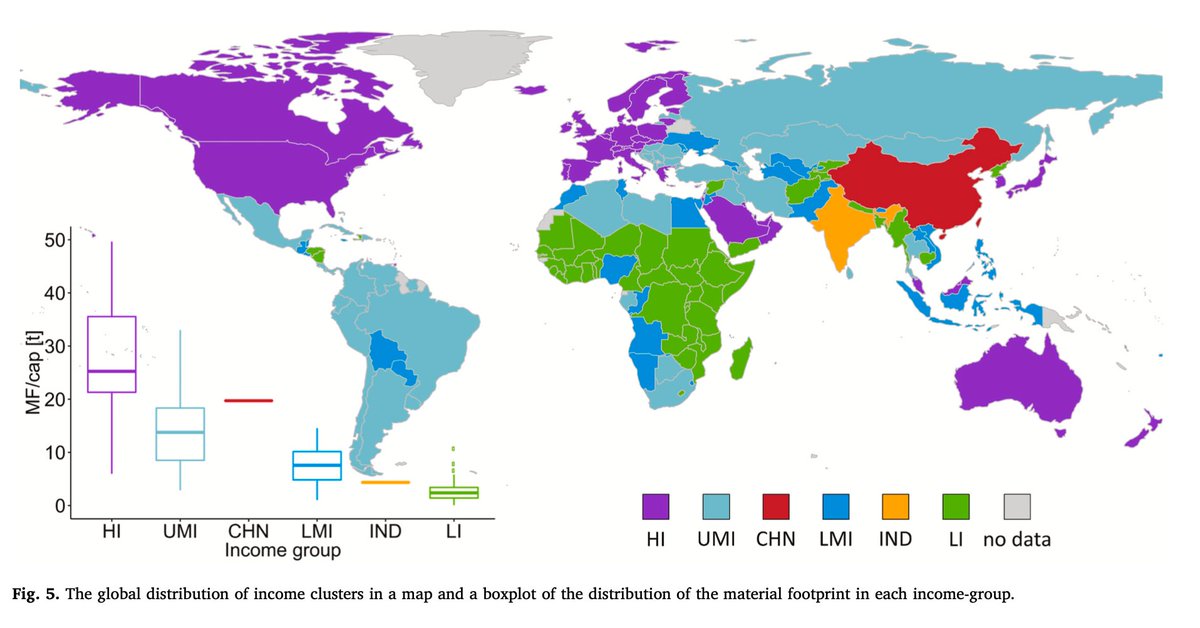

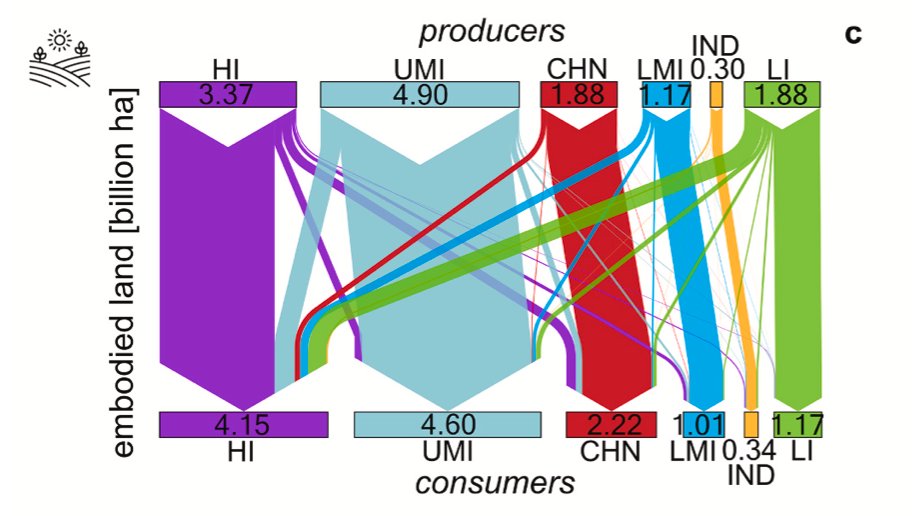

Across the embodied flows of materials, energy, land, and labor, rich countries (in purple) used more resources from a consumption perspective than they provided through production.

For example, high-income countries are the largest net appropriators of land (of approximately 0.8 billion hectares per year). Their land footprint correspond to 31% of total global land used.

While acting as a net appropriator of embodied resources, the group of high-income countries was able to accumulate a monetary trade surplus of approximately 1200 trillion USD over the 1990–2015.

The crucial variable de-termining access to resources and trade in value added for exports was economic power, i.e. per capita Gross National Income.

In standardized accountings of trade, money and materials flow in opposite directions. But when embodied resources are considered, net flows of money and resources goes in the same direction. Rich nations accomplish a net appropriation of materials, energy, land, and labor.

Implication: we cannot all grow. Since this growth-based model of development requires the appropriation of resources from poorer regions, it seems illusory for all poorer nations to be able to ‘catch-up.”

Another implication: further development in the global South requires #degrowth in rich countries who currently monopolise materials, energy, land, and labor.

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

END THREAD

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

END THREAD

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh