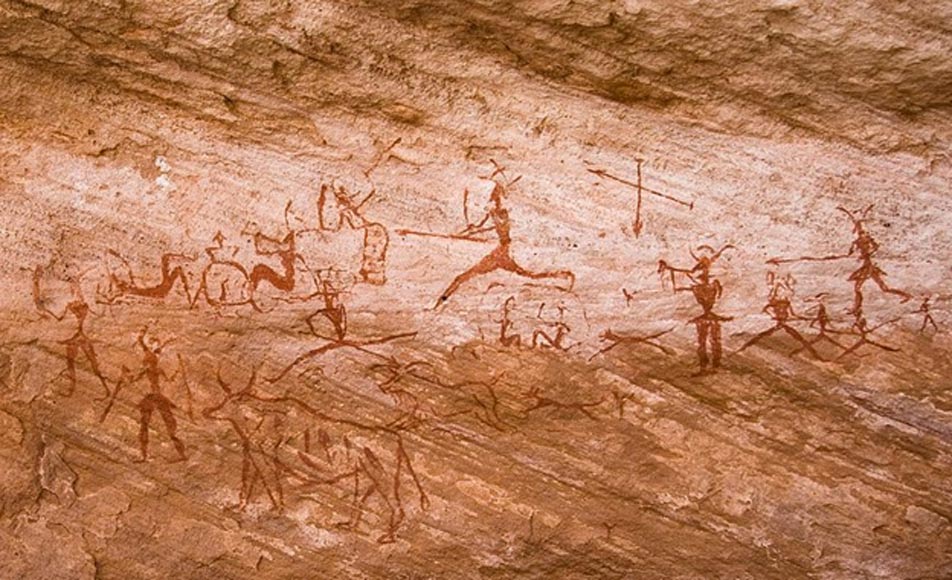

I like the idea that we may one day be able to write formal histories of the age before history. We’re learning so much about the distant past that it’s becoming possible to construct actual narratives of events that predate the dawn of writing. Thread

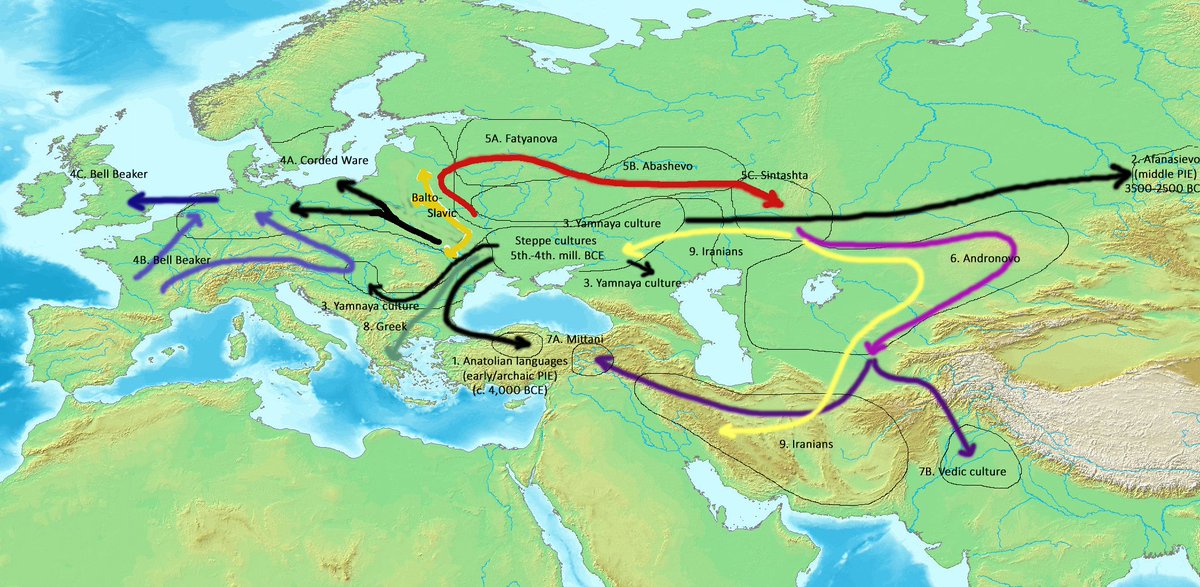

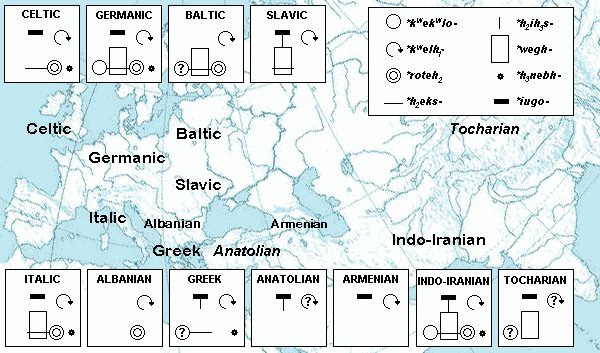

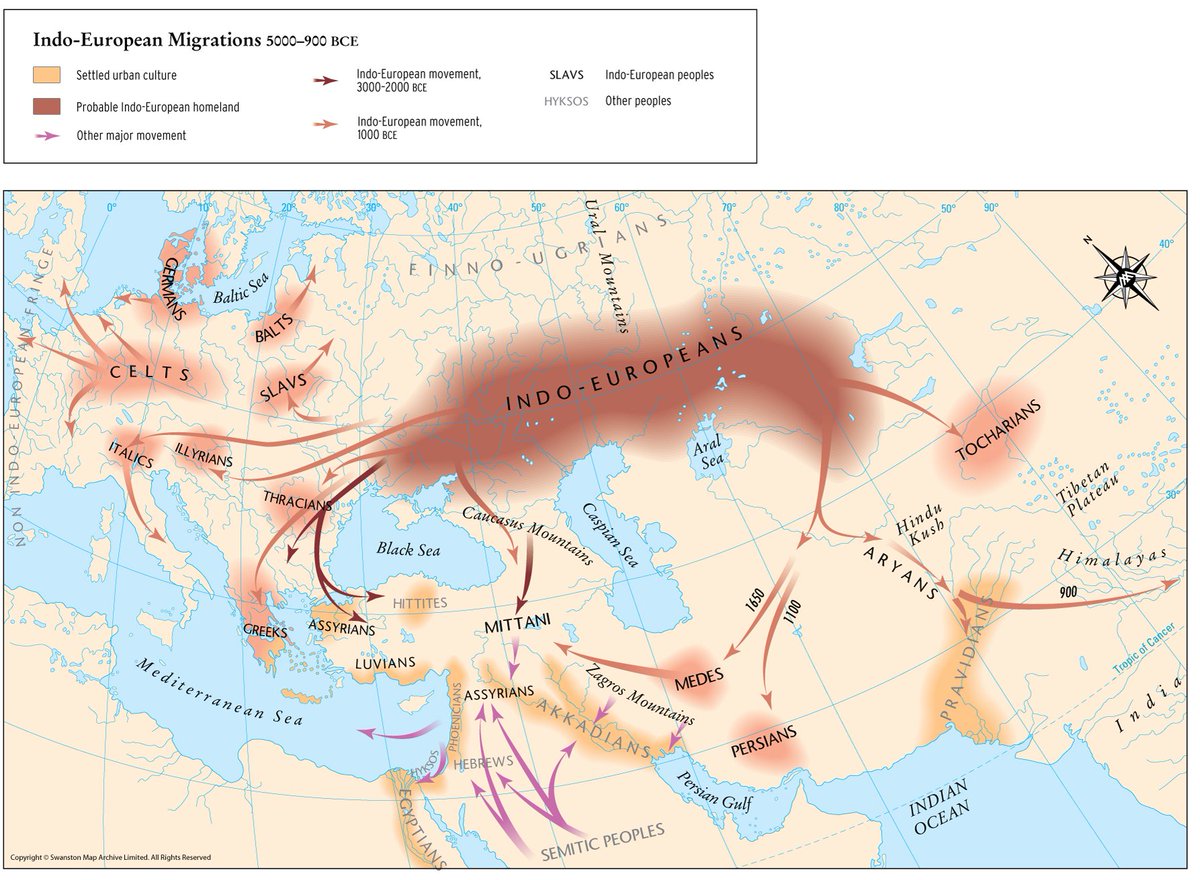

The most famous example of prehistoric narrative is the Indo-European expansion. Using DNA research, linguistics, and archaeology, scholars from various backgrounds were able to piece together a comprehensive picture and timeline of their expansion into Europe and Central Asia.

For instance: many widely-dispersed Indo-European languages share common words for carts, wheels, yokes, etc. This, together with other words, paints a picture of a horse-riding pastoralist society which used carts and lived somewhere on the Eurasian steppes.

Much of this has been confirmed by archaeological finds, correlated to genetic markers at gravesites across Europe and Central Asia—combined with language distributions, we have a very detailed picture of IE conquests down to half- or quarter-centuries.

But we can go farther back than that, to the Early European Farmer populations which were displaced by the IE expansion.

https://twitter.com/byzantinemporia/status/1262923676367958017

Scientists were able to develop statistical models of the actual diffusion of specific styles of monuments, the construction of which involved tens or hundreds of thousands of man-days. This already suggests complex societies and extended trade links.

https://twitter.com/Peter_Nimitz/status/1262936695160238080

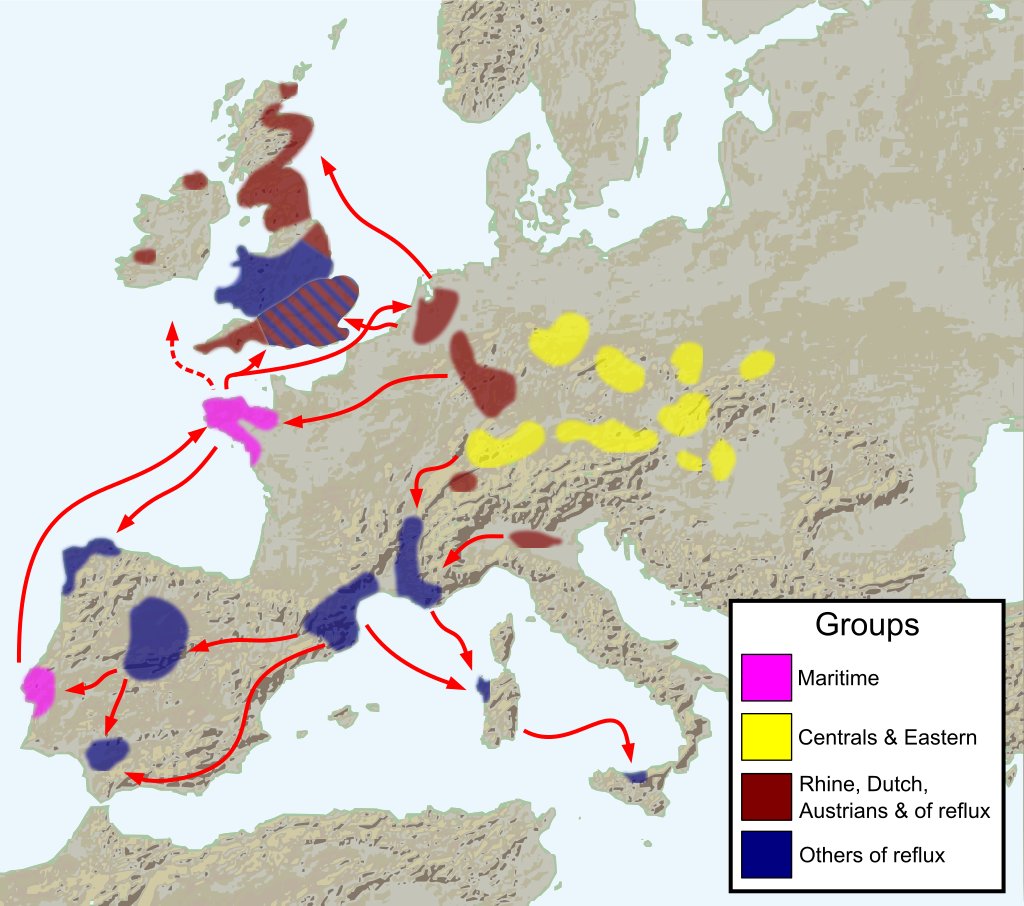

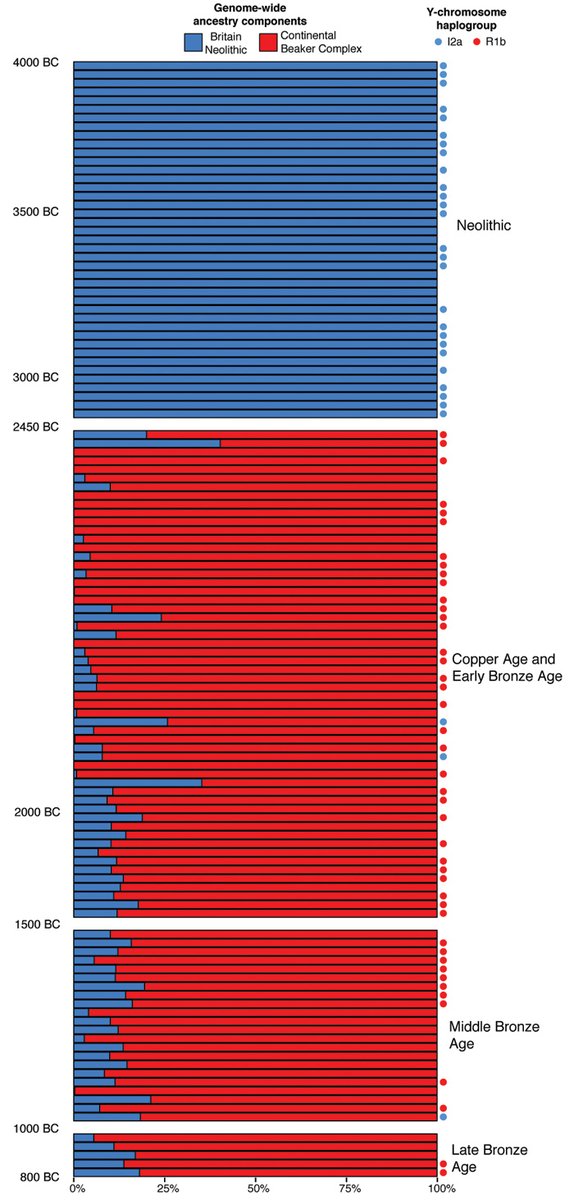

We get closer to describing actual history when we see cultural flows that are DISTINCT from concurrent genetic flows. We see that with one IE group, the Bell Beaker culture, named for their distinctive pottery, which spread through Europe in the 3rd millennium BC.

For the most part, Bell Beaker finds correspond pretty well to distinct IE genetic markers.

But not in Spain. What does this mean? A marriage alliance? A conquering elite? It is also intriguing that this culture shows up in isolated pockets, separated by great distance.

But not in Spain. What does this mean? A marriage alliance? A conquering elite? It is also intriguing that this culture shows up in isolated pockets, separated by great distance.

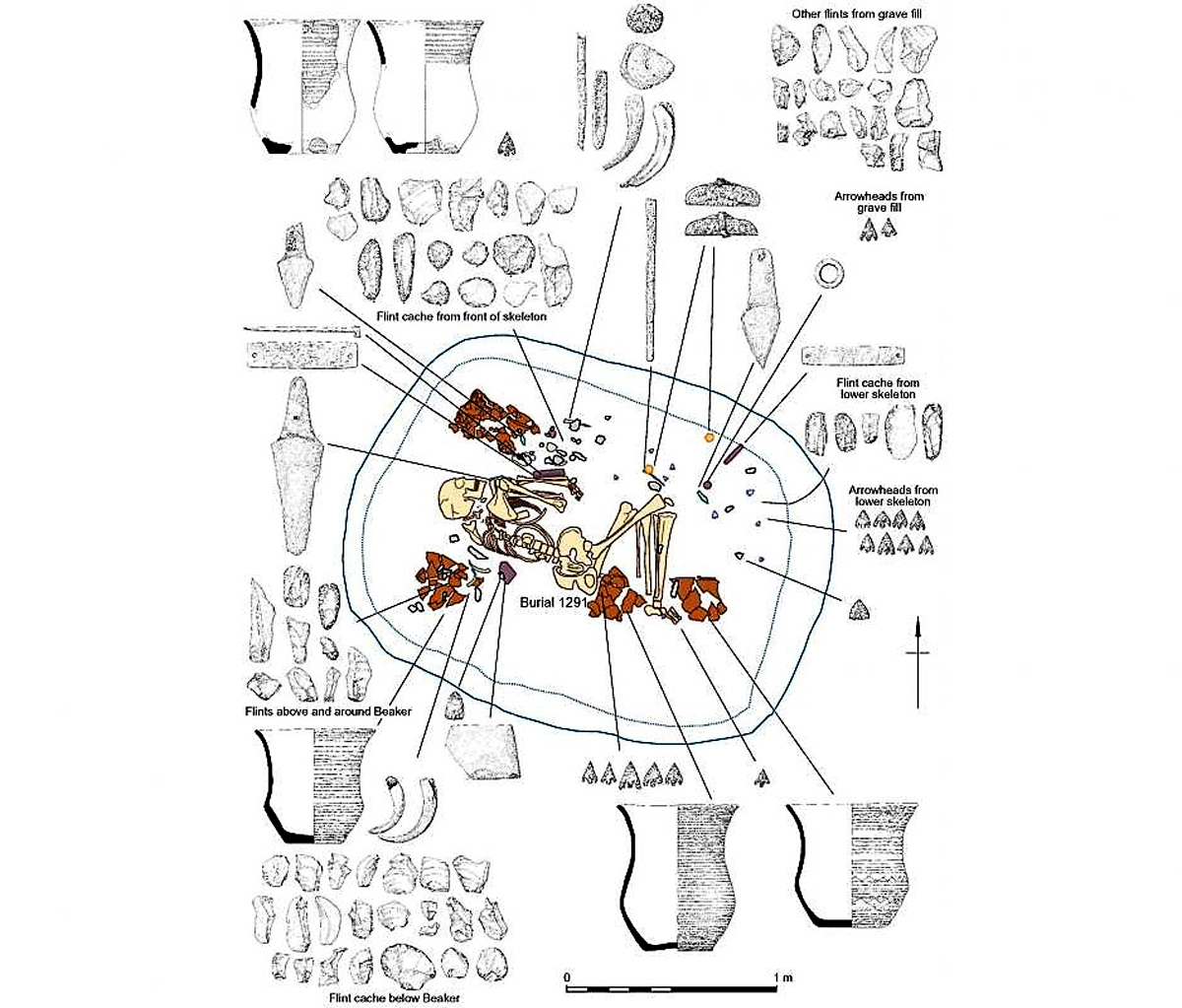

This case gets especially interesting when we look at their expansion into Britain after 2450 BC. One particularly intriguing Bell Beaker find is the Amesbury Archer, a man given a rich burial near Stonehenge.

The quantity and type of grave goods suggest that he was a high-ranked warrior, with tools to make arrowheads and repair his copper weapons, and biological markers indicate he was from the Alps.

This already suggests a trans-European network of some sort.

This already suggests a trans-European network of some sort.

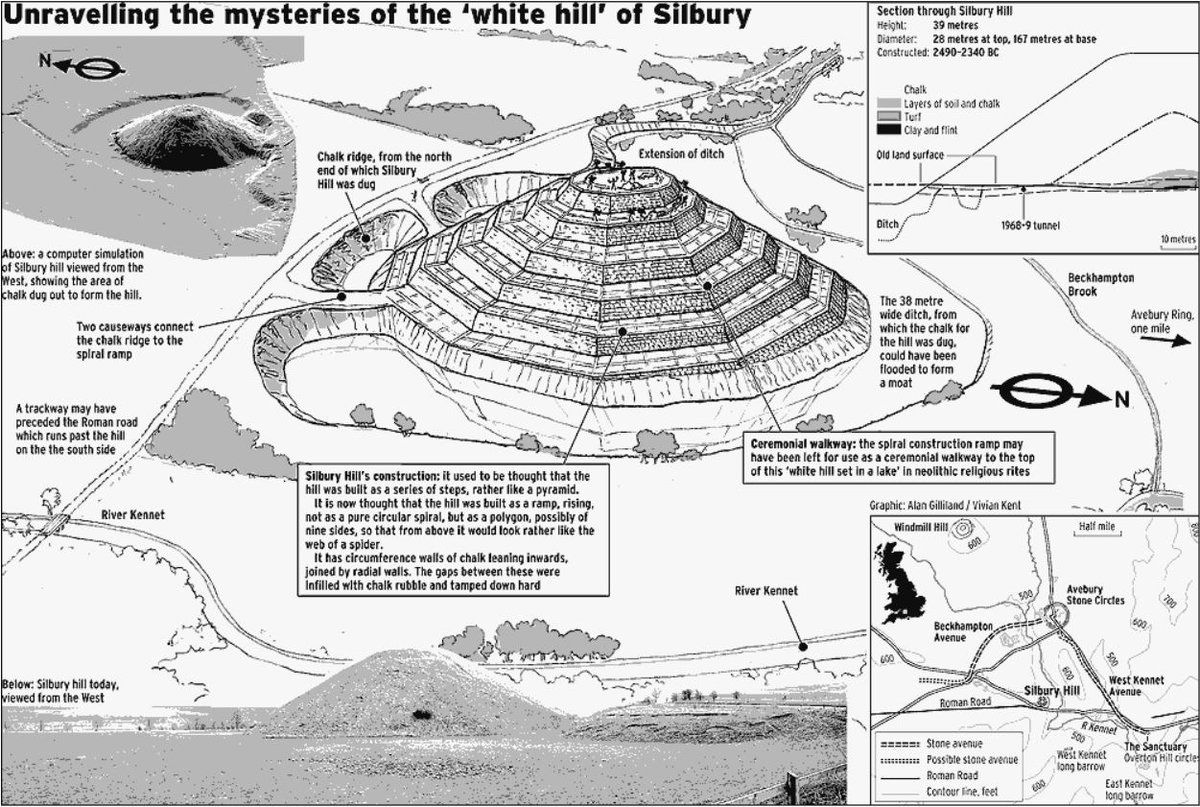

The context of his arrival is also interesting, estimated sometime in the 2300s BC, not long after the Bell Beaker people’s arrival. That is also when the Silbury Hill burial mound was being constructed, the largest mound in prehistoric Europe.

Its sheer size suggests a complex effort by a state with a lot of resources.

This, combined with a very rapid conquest of Britain—there was an abrupt genetic turnover within just a few centuries of 2450 BC—suggests a high level of organization.

This, combined with a very rapid conquest of Britain—there was an abrupt genetic turnover within just a few centuries of 2450 BC—suggests a high level of organization.

What else is out there that can tell us more? Battlefield sites and burned villages that show the pattern of expansion? Genetic analysis of gravesites that trace out kinship relations across space and time?

Who knows what discoveries are waiting to be made—these things area always serendipitous. But given the wealth of discoveries so far, there’s a good chance that lots more will be found, whether in Britain or on the Continent.

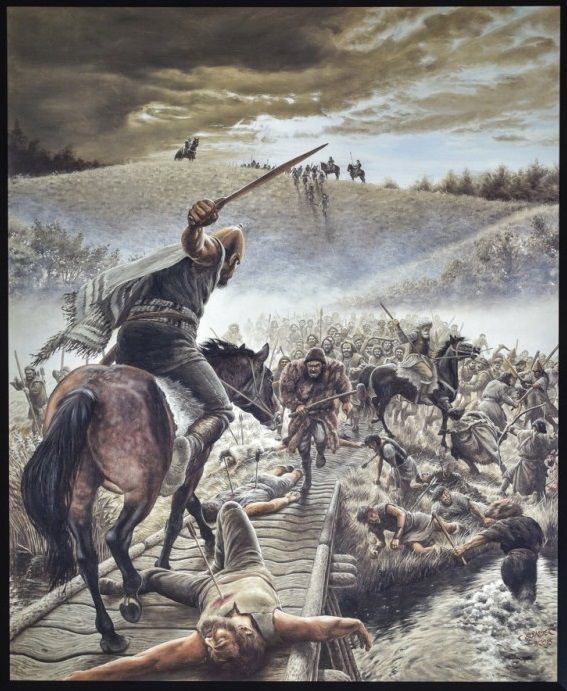

Getting closer to the historical age, one recent find gives us an idea of what this might look like. Sometime between 1300 and 1200 BC, a massive battle was fought in the Tollense valley in northeastern Germany.

Around 140 corpses were found as well as at least five horses and countless body parts—archaeologists estimate this amounted to a total of nearly 1000 dead—this would mean several thousands at least participated in the battle.

The battle was fought near a causeway, which has been partially preserved, suggesting one side was defending a river crossing.

More intriguing still is the genetic evidence from the corpses. Only some match local gravesites, the rest came from a wide range in the steppes far to the east—was this an invasion by some nomadic confederation? If so, who were the defenders and how big was their territory?

Matching up equipment to genes, it should be possible to create a story from any similar sites that are found in the future—the area has lots of peat bogs, which preserve biological material exceptionally well.

The Tollense site already tells a story, a lot of details can be filled in: the size of kingdoms, rough boundaries, trade networks, and whatever out-of-the-blue evidence might tell us about its causes.

This is where history begins, with stories of kings and battles.

This is where history begins, with stories of kings and battles.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh