Well, you asked for it, so here it is: a brief history of the mighty ampersand! #BreakfastPaleography

The character we know as the ampersand [&] is used in nearly every Latinate language as a stand-in for the word [and]. But it didn’t start life as an abbreviation. It is actually a ligature, a Latin combination of two letters: [e] and [t], or [et], which in English means [and].

Now that you know that much, you can sort of tell that early ampersands are a capital [E] connected to a [t], right? But then the basic form gets stretched and twisted and transformed until it doesn’t really look like e+t anymore.

As with most lower-case Latinate letters, we first meet the [et] ligature in New Roman Cursive, developed in the 3rd century C.E.

But it isn’t alone; there are several other [e] ligatures as well. The way [e] is written, the final horizontal stroke lends itself to ligation with [c], [d], [g], [m], [n], [r], [s], [t] and [x].

In 9th-c. Caroline, however, [e] is only ligated with [t]. Why? I don’t know! Maybe because it’s the only [e] ligature that is also a word? Suddenly, [et] becomes [&] pretty consistently, whether as the whole word or in the bigraph within a word.

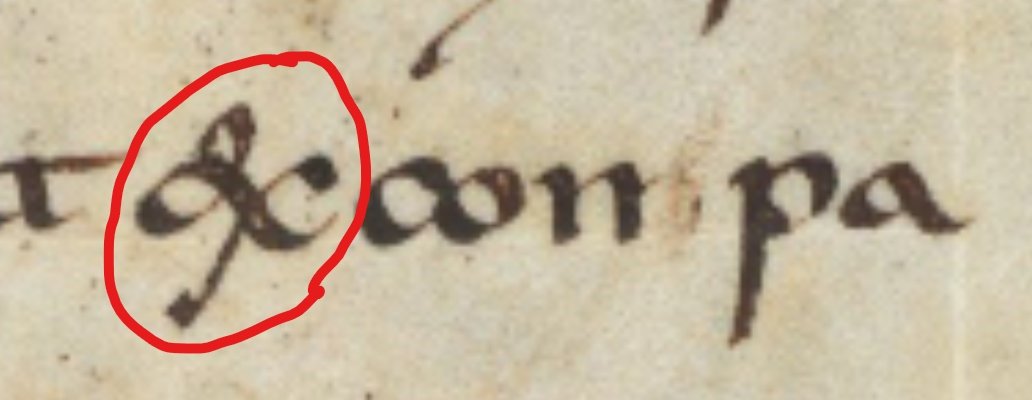

BUT [e] continues to be found in ligature with other letters in insular manuscripts as late as the 11th century! Sometimes it still looks like e+t, but sometimes it just doesn’t.

As we move into the proto-Gothic, or Romanesque, period (11th-12th c.), we start to see the Tironian form of [et] (looks like [7]) used as well. [&] is a ligature; [7] is an abbreviation. Gottschalk of Lambach uses both:

By the time Gothic quadrata and other Gothic scripts are fully developed in the 13th c., [&] is generally replaced by [7] to indicate [et]. Why? I don’t know! N.b. In northern Europe, [7] has a crossbar (l). In Italy, it doesn’t (r).

But when those Humanists like Petrarch and Boccaccio revive Caroline models in the 14th century, they also bring back the mighty ampersand, which no longer looks anything like an [e] joined to a [t]. As with [g], the Humanistic form look an awful lot like the [&] Twitter uses!

And what about the English word “ampersand”? First documented in 1797, it is a contraction of the phrase “and per se and” (“’&’ by itself is ‘and’”).

French “esperluette” may have a similar origin, “et per lui et”. The German term, in typical straightforward German fashion, is simply “Et-Zeichen” (“et symbol”). The end!

Epilogue: Modern typography (and @JonathanHsy) LOVES a good [&]. Here are some that were collected by the great paleographer B. L. Ullman.

I found these in his archive, which is in the @medievalacademy office. Ullman was my Doktor-Urgroßvater (my PhD advisor’s advisor’s advisor), so a love of ampersands must run in the family!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh