Read this book over shabbat (also the last six shabbatot, and during the week, and still only finished it after shabbat)

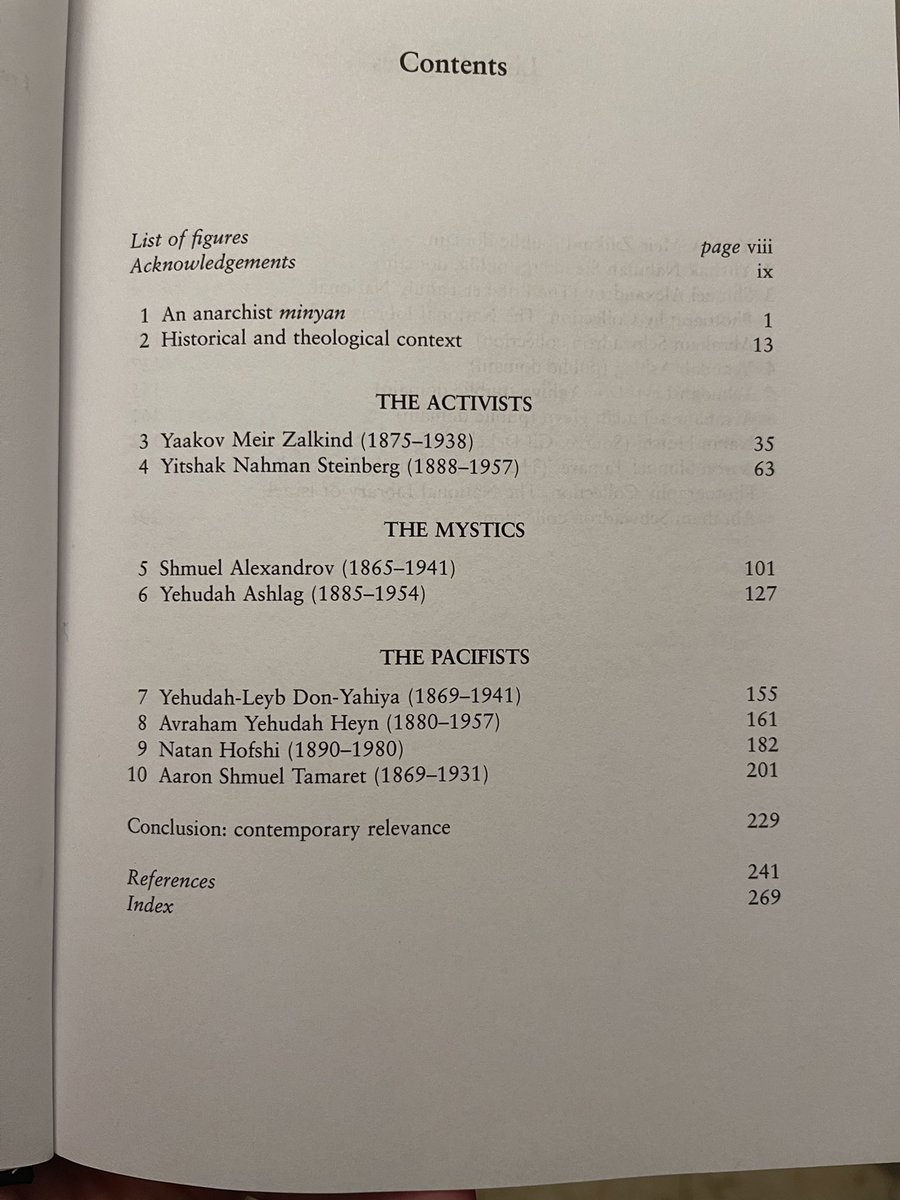

The book gives “portraits” of different “anarcho-Jewish” thinkers. Here’s the ToC, where they’re grouped as activists, mystics, and pacifists:

“Portrait” is the right term. Each 20–30-page chapter has a brief biography followed by thematic sections exploring different aspects of each thinker’s “Anarcho-Judaism,” that being Rothman’s term for their different fusions of Anarchism and Judaism, seeing Judaism as

anarchistic, and Anarchism as Jewish. Each figure did this differently, but all of them wanted to hold the two together, in contrast to figures like Gustav Landauer who consciously left Judaism behind and embraced Anarchism.

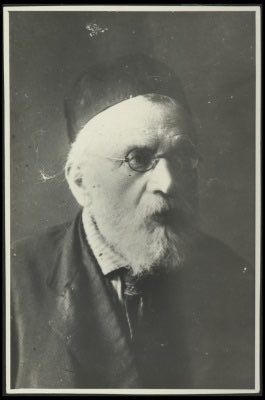

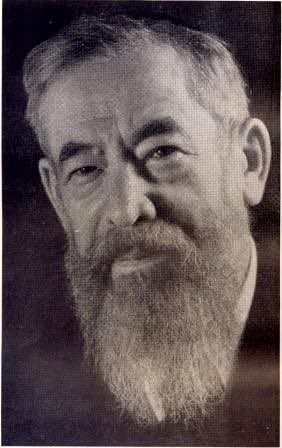

Two of my favorite chapters were the ones on the mystics: The Baal HaSulam, about whom I had known a decent amount (such as his communism, though not his anarchism), and Shmuel Alexandrov, who I knew only as someone to whom Rav Kook wrote letters. Rothman diligently

traces the mystical underpinnings of their anarchisms, as well as showing how the Baal HaSulam works with (and against) Schopenhauer, while Alexandrov is working with Schelling.

I was also particularly partial to the chapter on Avraham Yehuda Heyn, whose single-minded interpretation of all of Judaism in light of the commandment, “Thou Shalt Not Kill”—specifically “kill,” rather than “murder”—was impressive and inspiring. Almost Levinasian,

he radically sanctifies the individual, but in doing so arrives not at a modern American libertarianism but at a libertarian socialism.

Unfortunately, Heyn’s במלכות היהדות, published by Mossad HaRav Kook, seems to be long out of print.

Unfortunately, Heyn’s במלכות היהדות, published by Mossad HaRav Kook, seems to be long out of print.

The conclusion helpfully draws together common themes, such as a near-universal embrace of radical pacifism (based on means-ends correspondence), some form of universalism, and complex (but mostly positive!) relationships with Zionism.

The whole book is full of interpretive gems, and the introduction has a great “theological context” section laying out some of the traditional Jewish materials with which the subjects were working—such as the anarchistic comments of R. Don Yitzhak Abarbanel!

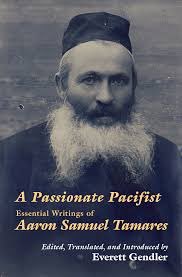

The final chapter on R. Aharon Shmuel (whose works were recently published in Hebrew by Blima Books and in English by @BenYehudaPress) included one of my favorite interpretations, a phenomenal rhetorical distinction:

Critiquing political Zionism, Tameret notes that while Political Zionists dream of returning to the land of the Israelite kings, Jews throughout history dreamed of returning to the land of the prophets.

On some level, the book suggests, that’s the choice: do we seek to be kings, or do we seek to be prophets?

@UnrollHelper unroll please

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh