1) Today is the official UK publication day of my new @OUPLaw book #preparingforwar on the making of the Geneva Conventions, the most important rules for armed conflict ever formulated.

THREAD.

global.oup.com/academic/produ…

THREAD.

global.oup.com/academic/produ…

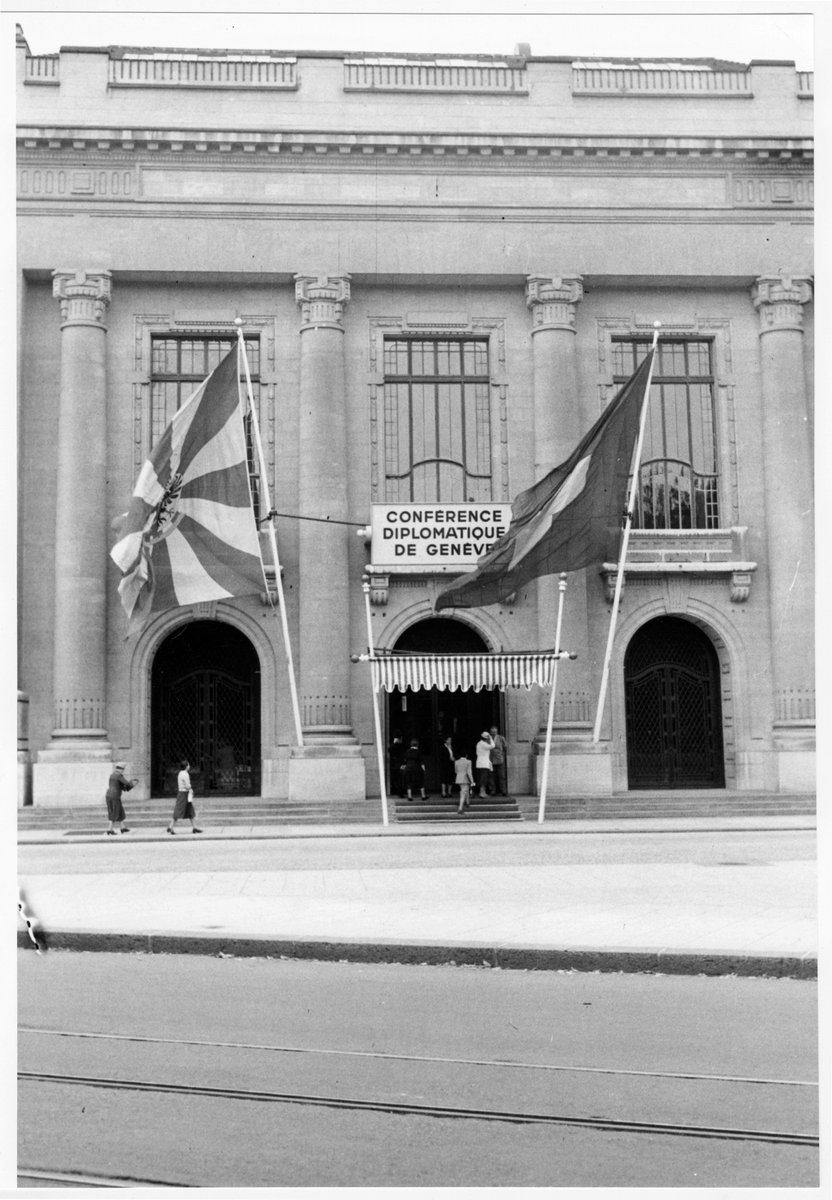

2) On the morning of 21 April 1949, at the diplomatic conference of Geneva’s opening ceremony, the Swiss president of the meeting Max Petitpierre welcomed state representatives from across the world to the city before a crowd of excited spectators.

3) They gathered at Geneva’s historic Bâtiment Électoral to further the idea of humanizing warfare. At the time, this building hosted the ICRC’s POW Agency and its millions of fiches chronicling the lives of POWs from WWII (see image).

4) These unique documents had to be temporarily stored elsewhere to allow the Swiss hosts to use the building for the diplomatic conference.

5) The conference finally agreed that civilians were to fall under the Conventions. It also updated the POW Convention, shielded civilians against indiscriminate bombing, protected guerrillas against torture, and extended these principles to civil wars for the first time.

6) This undertaking, which was professionally managed by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), was truly universal, with the participation of delegates from Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Latin America.

7) The ultimate result was the adoption of four new Conventions, thereby satisfying the world’s deep- rooted desire for catharsis in the wake of the war’s appalling brutality – epitomized by the Holocaust.

8) That is the received master narrative of the making of the 1949 Conventions. According to this story, drafters were primarily motivated by the shock of atrocity and inspired by (liberal-)humanitarian principles.

9) These treaties were said to be the product of a long tradition of liberal humanitarianism, dating back to Henri Dunant’s pioneering efforts following the Battle of Solferino (1859).

10) My book tells a different story. I show how the final text of the Conventions, far from being an unabashedly liberal blueprint, was the outcome of a series of political struggles among the drafters, many of whom were not liberal and whose ideas changed radically over time.

11) The Soviets (see image) played a crucial part, for instance, in coining proposals for civilian protection and gathering crucial support for plans to end inhumane measures in war. The idea that the Conventions are mainly the product of liberal thinking is unsustainable.

12) Nor were the drafters merely a product of idealism or even the shock felt in the wake of Hitler’s atrocities. It concerned a great deal more than simply recognizing the shortcomings of international law as revealed by the experience of the Second World War.

13) I argue that a better way to understand the politics and ideas of the Conventions’ drafters is to see them less as passive characters responding to past events than as active protagonists trying to shape the future of warfare.

14) In many different ways, they tried to define the contours of future battlefields by deciding who deserved protection, what counted as a legitimate target, whose lives mattered, when these principles applied, and who had the right to enforce them.

15) Why is this important? One way of answering this question is to look at how the Conventions are remembered today - and what lessons are being drawn for future lawmaking efforts.

16) When looking back on the imperfect making of Common Article 3, many observers argue that drafters had not anticipated that civil + colonial wars would multiply in the decades after 1949, therefore allegedly making it less equipped for the future.

icrc.org/en/document/5-…

icrc.org/en/document/5-…

17) This is an unfortunate myth – i.e., the idea that humanitarian law is always backward-looking. In reality, especially imperial powers such as the UK expressed major concern about such plans to regulate civil and colonial wars.

18) They feared more so-called 'internal wars' were to come in the future, therefore trying to destroy those plans to widen international law's scope as they were fighting brutal wars of counterinsurgency in colonial spaces like Malaya (see image).

19) Similarly, when demanding rights in interstate wars in response to Vichy + Nazi occupation, French drafters felt forced to bring this progressive project into line with their brutal counterinsurgency campaign in Indochina - and the ones in the future.

20) The book also points out why accounts of the law's emergence that focus exclusively on WWII, or Dunant, fail to explain why some proposals were codified whereas others were scrapped, or why states formerly occupied by the Axis had not been brought together by this experience.

21) These accounts cannot resolve the historical puzzle of why, for example, the French accepted an extrajudicial security clause despite the fascist occupation, or the British condoned the use of indiscriminate bombing despite the Blitz.

22) In the 1940s, questions concerning the kind of law that would exist in future wars and the forms of violence it would tolerate were on the line. The stakes were high: the ‘fate of millions of human beings depended on what would happen in Geneva,’ wrote one Swiss reporter.

23) In drafting new rules for warfare, a range of further issues was in question: the sovereignty of states; the ICRC’s credibility; the character of international order; and the forms of power and control that that system wished to exert over people’s lives in war.

24) UK-US drafters pushed for the most regressive solutions and opposed further restrictions on occupation. This should come as no surprise. After all, these two liberal powers fought the most wars in the twentieth century - more even than Germany.

jstor.org/stable/4010837…

jstor.org/stable/4010837…

25) In trying to maintain a free hand in ongoing + future military operations and condoning the use of destructive weapons against their enemies, UK drafters had to ask themselves time and again whether they could credibly claim to be upholding ‘civilization’ in wartime.

26) UK drafters had to engage with public expectations with regard to the effort to humanize warfare. At the very least, they had to look responsive when victims of occupation demanded that 'Nazi-style' counterinsurgency policies, such as the killing of hostages, be outlawed.

27) Whereas Nuremberg is sometimes framed as 'victors’ justice,' Geneva was seen as ‘victims’ justice’ instead – at least in the eyes of several drafters.

28) UK delegates could not afford to ignore the precedents set at Nuremberg, Tokyo, and other criminal tribunals, which had proclaimed higher standards for the conduct of warfare.

29) Complaining about the Conventions being used ‘demagogic[ally]’ to further Anglo-American interests, the Soviets tried to widen the scope of the agreements to encompass civilian populations. In this way, they hoped to curtail US air power and spread Cold War propaganda.

30) In so doing, the Soviets turned the diplomatic conference into a forum for Cold War and anti-colonial politicking, in which Western adversaries could be criticized on an international stage.

31) Western powers were made vulnerable by their ongoing counterinsurgency campaigns, which the Soviet Union - their former ally in WWII - characterized as being reminiscent of fascist practices.

32) ‘Behind the seemingly calm discussion of the Conventions,’ wrote a Soviet delegate later, ‘a fierce fight [had been] lingering between [the] delegations.’

33) By placing the history of the Conventions back in the context of decolonization, the Cold War, and global politics, my book shows how the ideas and politics driven by these processes had a profound impact on how the drafters reconfigured international law’s genetic code.

34) The book presents individuals who defy expectations. We encounter survivors of Nazi persecution who battled against new rules for enforcing the law. We face UK drafters who offended their US allies, broke conference rules, and pressured NATO partners to support their ideas.

35) And we read about postcolonial delegates who took the moral high ground and enjoyed the Schadenfreude of witnessing their former imperial rulers struggle in Geneva.

36) We also get to know ICRC/Swiss delegates who used the principles of human rights against those in power to demand a more humane version of occupation. This may seem puzzling to some experts.

37) Others have argued, for instance, that human rights and humanitarian law ‘were neatly and completely separated, [both] intellectually and in practice’ during the 1940s.

38) In reality, (see image of Petitpierre and Roosevelt meeting in the 1940s as the two most important representatives of hum rights and hum law), drafters saw measures like hostage taking as a violation of the rights and dignity of victims of war – a decisive conceptual shift.

39) The most important consequence of this shift was that it led to continuing calls for placing greater restrictions on the conduct of warfare – on collective penalties, reprisals, state destruction, etc., and for recognizing the right to have rights in wartime.

40) But the Conventions were far from perfect - which raises the question about what might have turned out differently. Which radical courses of action were not taken in Geneva in 1949?

41) There were many roads not taken. Drafters considered combining different issues (see image), for instance, and initially agreed upon the need to recognize the principle of distinction in aerial warfare. The grave breaches system could have been given more teeth.

42) There were often good reasons for the drafters reaching different conclusions. That said, there was nothing inevitable about the demise of some proposals and the adoption of others – a lesson that can inspire hope in enabling us to imagine a more humane future.

43) At the same time the drafters were not perfect. They failed in trying to persuade Anglo-American drafters to accept restrictions on air bombing, nuclear weapons, and starvation, which would directly undermine the ICRC’s operations in Biafra two decades later.

44) While imperfect, Geneva’s drafters made a real difference. Among other things, they banned the use of hostage taking, reprisals, gave more rights to POWs, strengthened the position of the ICRC in wartime, and laid the conceptual groundwork for the ICC’s legal guidebook.

45) But some of these achievements are now at risk. This is a crucial issue, since states are preparing again for new wars – across the Middle East, in Ukraine, and over Taiwan, raising fundamental questions about the future of international law in wartime.

46) History is useful in making us more aware of what is now at stake – e.g. the importance of law in war.

47) If int law is to survive in this period of growing preparations for all-out war in Europe and Asia, its champions need to have their voices heard and send out a clear signal to those responsible for atrocities such as the recent bombing in Yemen. bbc.com/news/world-mid…

48) If you'd like to know more about #preparingforwar, I'd recommend taking a closer look at the book's website.

preparingforwar.org

preparingforwar.org

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh