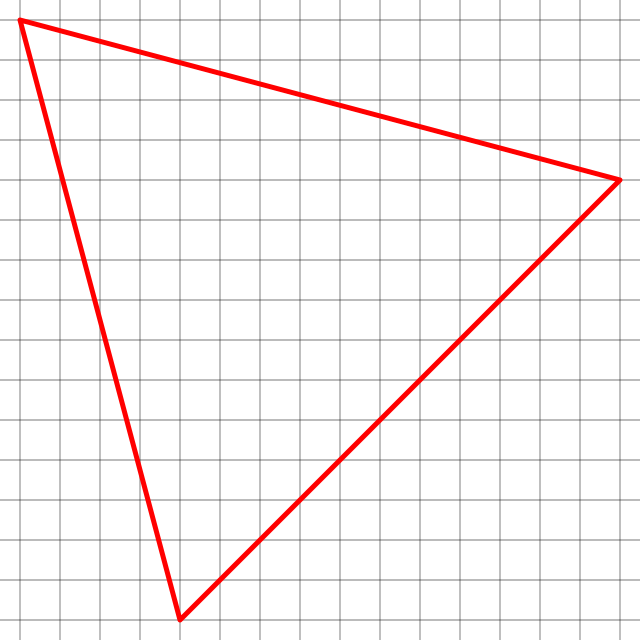

If I claimed that these three vertices of a square grid form an equilateral triangle, would you believe me? A few thoughts on this question. 🧵⤵️ •1/26

Well, assuming you're not the sort of person who uses a ruler to measure on a monitor (in which case it may be hard to make the call), maybe you use the Pythagorean theorem and compare 4²+15² = 241 to 11²+11² = 242 to conclude that the bottom-right edge is a bit longer. •2/26

But maybe you just know that there are no three vertices of a square lattice that form an equilateral triangle: so I must have cheated. This seems to be the sort of math fact that everyone knows somehow. But why is it true, again? •3/26

It's interesting because it's the sort of thing one can prove in a dozen different ways. Or maybe they're all the same, really, as they all ultimately relate to √3 being irrational (but still, one needs to say a bit more). •4/26

For example, this Math StackExchange question has five answers each giving a different flavor of proof (and the question itself also gives one, and there are more proofs in the links to duplicates of the question): math.stackexchange.com/q/1359762/84253 •5/26

(It's often interesting to ponder, when we have several proofs of the same fact, whether they are the “same deep down”, although I don't think this has any precisely defined meaning — maybe HoTT people can say whether two proofs are homotopic? I don't know.) •6/26

The proof in my head goes like: if u,v,w had rational coordinates and formed an equilateral triangle, then as complex numbers they are in the field ℚ(i) = {a+b·i : a,b∈ℚ}, so (w−u)/(v−u) = exp(±iπ/3) = (1±√3·i)/2 is in it too, which is not the case as √3∉ℚ. ∎ •7/26

The proof in the above tweet is impelled by the irrationality of √3, but also by the fact that ℚ(i) is a field. (In more sophisticated terms, we compute ℚ(i)∩ℚ(exp(iπ/3)) = ℚ by noting that their compositum contains ℚ(√3) which is not equal to ℚ. Or something.) •8/26

Now the purely geometric argument given in math.stackexchange.com/a/1360531/84253 (which is pretty much the argument given here:

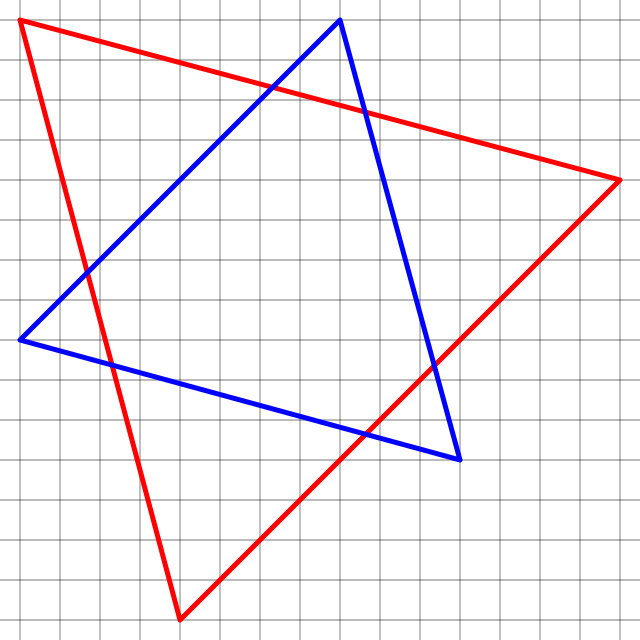

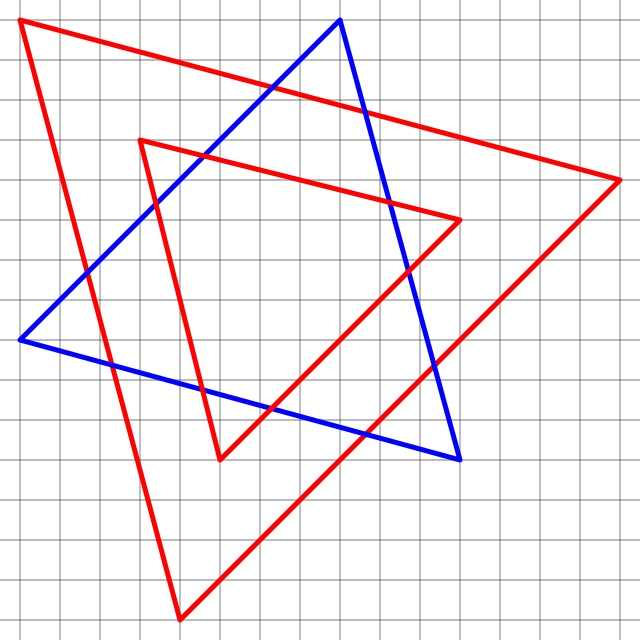

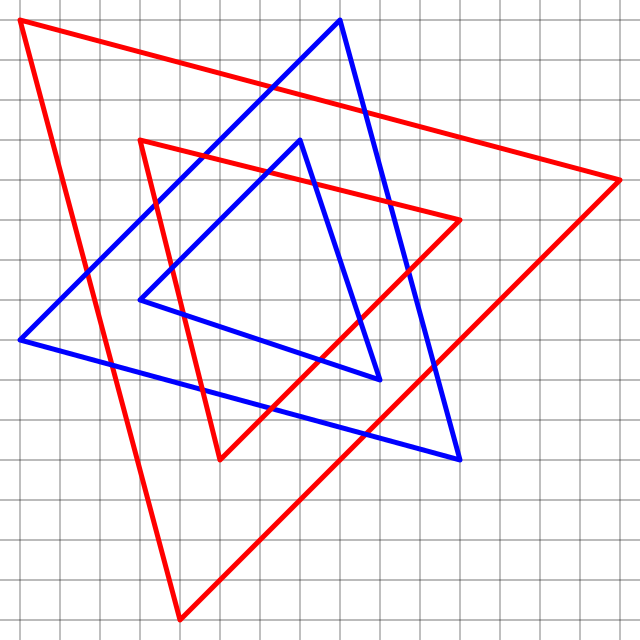

https://twitter.com/JDHamkins/status/1154516551724388352) is also interesting: essentially, it says, replace (u,v,w) by (u′,v′,w′) := (u+i(v−w), v+i(w−u), w+i(u−v)): … •9/26

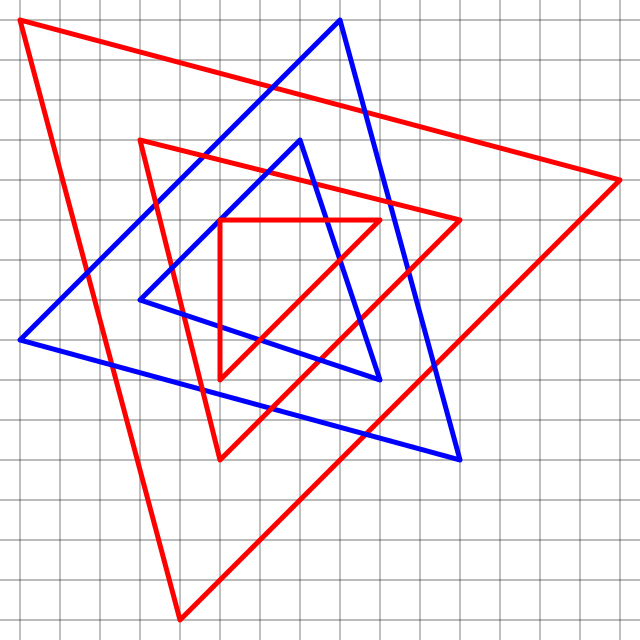

… if u,v,w are in the square lattice ℤ[i], then so are u′,v′,w′, and if they were an equilateral triangle, the new one too, with smaller area, leading to infinite regress. If we iterate this for the triangle above, we get less and less equilateral, revealing the fraud! •10/26

I don't know if there's something intelligent to be said about the fact that this argument, unlike the one in tweet 7, doesn't involve any division. Or about the matrix [[1,i,−i], [−i,1,i], [i,−i,1]] which gets iterated on the coordinates in this argument. •11/26

But here's another, more “constructive”, way to approach the question of finding equilateral triangles in a square lattice: if we can't find any exact ones, how can we build approximate ones? •12/26

This is essentially the problem of finding approximations of ω := exp(iπ/3) by the ratio of two elements of ℤ[i] := {a+i·b : a,b∈ℤ}, the “Gaussian integers”. (Indeed, if p/q ≈ ω with p,q∈ℤ[i], then the triangle 0,p,q is close to equilateral.) •13/26

Now there's a Euclidean algorithm to approximate real numbers by rationals, which also works to approximate complex numbers by ratios of Gaussian integers. It works as follows: if you want to approximate ξ, find an integer n₀ close to ξ, … •14/26

… now replace ξ with 1/(ξ−n₀), find n₁ close to it, and repeat the same process “subtract n and invert”. You get a sequence n₀,n₁,n₂,… representing a “continued fraction” n₀ + 1/(n₁ + 1/(n₂ + 1/(…))): truncating this at finite levels gives approximations to ξ. •15/26

More precisely, the Euclidean approximation algorithm goes like this:

‣ start with ξ given, (p,q,p′,q′)←(1,0,0,1),

‣ repeat: n ← integer_approx(ξ), (p,q,p′,q′) ← (n·p+p′, n·q+q′, p, q), print(ξ,"≈",p,"/",q), ξ ← 1/(ξ−n) while ξ≠n in this last step.

•16/26

‣ start with ξ given, (p,q,p′,q′)←(1,0,0,1),

‣ repeat: n ← integer_approx(ξ), (p,q,p′,q′) ← (n·p+p′, n·q+q′, p, q), print(ξ,"≈",p,"/",q), ξ ← 1/(ξ−n) while ξ≠n in this last step.

•16/26

When approximating real numbers with rationals, the “integer_approx” function above is usually taken to be the “floor” (integer part) function. But it doesn't change much to use the “closest integer” function (we just might get negative values of n). •17/26

We can use the exact same algorithm to approximate complex numbers by ratios of Gaussian integers, taking integer_approx(ξ) to return the closest integer on the real and imaginary parts of ξ separately (and rounding however we want if we're exactly halfway). •18/26

(If you wonder why I write “ratio of Gaussian integers” rather than elements of ℚ(i), yes, they are the same, but the point is that the algorithm provides irreducible fractions p/q of Gaussian integers, which, for triangles of integral points, is precisely what we seek.) •19/26

If we use this algorithm to approximate ω := exp(iπ/3) = (1+√3·i)/2, we get successively (rounding toward 0 in case of equality): i, (1+2i)/2, (4−i)/(1−4i), (−7+4i)/(8i), (−4−15i)/(−15−4i), (−15−26i)/(−30), etc. Triangles closer and closer to being equilateral. •20/26

The continued fraction expansion here is ω = i + 1/(2 + 1/(−2i + 1/(−2 + 1/(2i + 1/(2 + 1/(−2i + 1/(−2 + 1/(2i + 1/(…)…). Now I didn't think about this, but I'm sure there's a way to describe this geometrically, maybe related to the construction in tweets 9–11. •21/26

And the fact that this continued fraction expansion doesn't terminate tells us “constructively” that ω can't be written as the ratio of two elements of ℤ[i] just as it tells us how to approximate it, just like the Euclidean algorithm in ℝ performs analogously. •22/26

(For example, in ℝ, we have 1 + 1/(2 + 1/(2 + 1/(2 + 1/(…)…) = √2, and this simultaneously witnesses the fact that √2 is irrational and tells us how to approximate it rationally. Quadratic irrationals have preperiodic continued fraction expansions, and conversely.) •23/26

I have to admit I'm still not clear as to what general context we can use the Euclidean algorithm in. For number fields I imagine we probably need the aptly named “Euclidean” (or “norm-Euclidean”?) property for it to work: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euclidean… … •24/26

… but the same algorithm given in tweet 16 can be used in other contexts, e.g., to compute so-called Padé approximants to real functions (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pad%C3%A9…), just replacing “integer_approx” by an approximation by a finite sum of c_k · (x−x₀)^k for k≤0. •25/26

Also, can we use the Euclidean algorithm to find close-to-regular pentagons, say, in a square lattice? (Or do we need more sophisticated algorithms like LLL?) I don't know! If you can think of a simple and elegant way to find them, in the spirit of the above, let me know! •26/26

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh