1/ Smartest Guys in the Room: The Amazing Rise And Scandalous Fall of Enron (Bethany McLean, Peter Elkind)

Skilling: “Enron was a great company.”

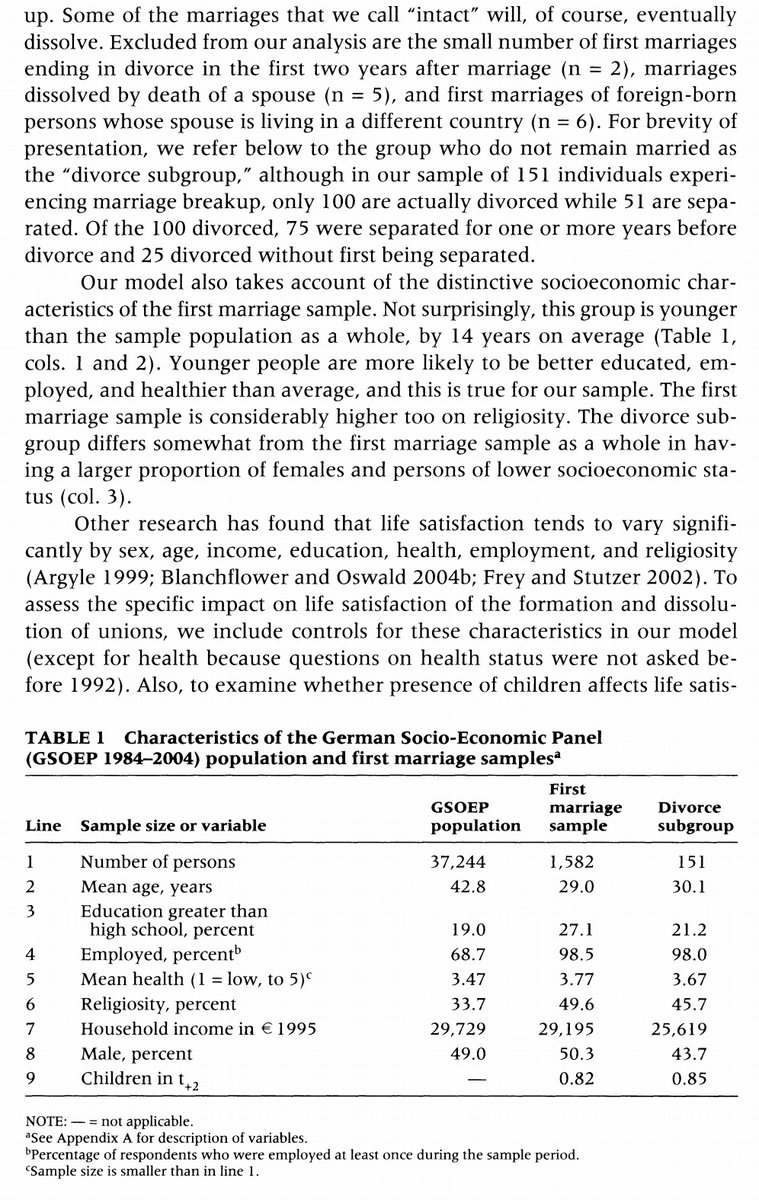

"Indeed, that’s how it seemed until the moment it filed the largest bankruptcy claim in U.S. history." (p.29)

amazon.com/Smartest-Guys-…

Skilling: “Enron was a great company.”

"Indeed, that’s how it seemed until the moment it filed the largest bankruptcy claim in U.S. history." (p.29)

amazon.com/Smartest-Guys-…

2/ "Fortune magazine named Enron “America’s most innovative company” six years running. Henry Kissinger & James Baker were on its lobbying payroll. Nobel laureate Nelson Mandela came to Houston to receive the Enron Prize. The U.S. president called Enron chairman Lay “Kenny Boy.”

3/ "Enron had transformed the way gas & electricity flowed across the U.S. It bankrolled audacious projects around the globe: state-of-the-art power plants in third world countries, a pipeline slicing through an endangered Brazilian forest, a steel mill on the coast of Thailand.

4/ "As Skilling saw it, Enron fell victim to a cabal of short sellers & scoop-hungry reporters that triggered a classic run on the bank. Privately, he would grudgingly acknowledge occasional mistakes—including the failure of Enron’s broadband venture, which cost >$1 billion.

5/ "Yet Skilling remained remarkably unwilling to accept any personal responsibility for the company’s demise.

"Enron, which once aspired to be known as “the world’s greatest company,” became a different kind of symbol—shorthand for all that was wrong with corporate America."

"Enron, which once aspired to be known as “the world’s greatest company,” became a different kind of symbol—shorthand for all that was wrong with corporate America."

6/ "The public scrutiny Enron triggered exposed additional epic business scandals—tales of cooked books and excess at companies like Tyco, WorldCom, and Adelphia." (p. 30)

7/ "Ken Lay was the go-to man for charitable works, raising and giving away millions. He spoke often about corporate values. “Everyone knows that I personally have a very strict code of personal conduct based on Christian values.”

"Lay was a hard man not to like.

"Lay was a hard man not to like.

8/ "His deliberately modest midwestern manner—Lay personally served drinks to subordinates along for the ride on Enron’s flagship jet—built a reservoir of goodwill. He remembered names, listened earnestly, and seemed to care what you thought. He had a gift for defusing conflict.

9/ "But this style, soothing though it may have been, was not necessarily well-suited to running a big corporation. Lay had the traits of a politician: he cared deeply about appearances, wanted people to like him, & avoided the sort of tough decisions that would make others mad.

10/ "His top executives—people like Jeff Skilling—understood this about him and viewed him with something akin to contempt. They knew that as long as they steered clear of a few sacred cows, they could do whatever they wanted and Lay would never say no." (p. 36)

11/ "By the time Lay and his minions in Houston realized something was wrong—more accurately, by the time they were willing to face what they should have seen all along—the oil traders had come within a whisker of bankrupting the company. This was the canary in the coal mine.

12/ "Borget and Mastroeni weren’t engaging in criminal acts just for the good of the company. They were stealing from Enron as well. They were keeping two sets of books, one that was sent to Houston and one that tracked the real activities of Enron Oil.

13/ "They were paying exorbitant commissions to the brokers who handled their sham transactions and demanding kickbacks.

"With Lay so willing to look the other way, they would have gotten away with it, except for the one mistake Enron couldn’t abide. They stopped making money.

"With Lay so willing to look the other way, they would have gotten away with it, except for the one mistake Enron couldn’t abide. They stopped making money.

14/ "For months, Borget had been betting that the price of oil was headed down, and the market had gone against him. As his losses had mounted, he had continually doubled down, ratcheting the bet in the hope of recouping everything when prices ultimately turned in his direction.

15/ "Finally, Borget had dug a hole so potentially catastrophic that there was virtually no hope of fully recovering.

"He called Houston immediately after the lunch and, in a panicked tone, declared that as a result of Borget’s trading losses, Enron was “less than worthless.”

"He called Houston immediately after the lunch and, in a panicked tone, declared that as a result of Borget’s trading losses, Enron was “less than worthless.”

16/ "But Enron got lucky. “If the market moved up three more dollars Enron would have gone belly up,” Muckleroy later said. “Lay and Seidl never understood that.” " (p. 62)

17/ "Enron found its visionary in Jeffrey Skilling. When Skilling looked at the natural-gas industry, he didn’t see natural gas. Instead, he saw the needs of customers on one side and the needs of suppliers on the other—and the gaps in between where serious money might be made.

18/ "He saw the ways in which the natural-gas industry resembled commodity businesses like wheat and pork bellies and especially financial services, where money itself is the commodity.

"Over time, his way of thinking helped revolutionize Enron and the natural gas industry.

"Over time, his way of thinking helped revolutionize Enron and the natural gas industry.

19/ "Skilling could conceptualize new ideas with blazing speed. He could simplify highly complex issues into a sparkling, compelling image. He presented his ideas with a certainty that bordered on arrogance and brooked no dissent. He used his brainpower to intimidate." (p. 69)

20/ "Although Enron was assuming the traditional role of the banker, it had major advantages. In extending a loan, a bank would try to err on the conservative side because it had no idea where the price of gas was going. If the price plummeted, the producer might go bankrupt.

21/ "(In fact, this had happened often after the energy bubble of the 1980s burst, which is why so many banks were in trouble.) But Enron knew the price it could get for the gas: it had already sold it. Because of that knowledge, it was able to lend far more than a bank would.

22/ "What’s more, Enron structured its deals so that it still had the right to the gas, even if the producer went under. After all, for Enron, getting the gas was what mattered. Finally the Gas Bank began to work: producers as well as customers were signing contracts.

23/ "Now that supply and price could be guaranteed, natural gas—which was far more environmentally friendly than coal—soon became an attractive fuel again for utilities. They began building new gas-fired plants." (p. 80)

24/ "The Gas Bank had been a physical hedge; trading took the next step. It freed Enron from having to own assets involved in production and transportation. In theory, instead of owning reserves and pipelines, Enron could own contracts to control the resources it needed.

25/ "Instead of seeing a commitment to deliver natural gas as something that necessarily involved a pipeline, Enron saw it as a financial commitment. It was a new concept that theoretically required less capital and would enable better pricing and more flexibility for customers.

26/ "Unlike other commodities, natural gas flowed 24 hours a day. Different hubs had their own pricing variations. There were transportation contracts, capacity contracts, which reserved space on pipelines... an almost infinite number of moving pieces." (p. 82)

27/ "In the beginning, the traders were their own small division. Their transformation from a support group to a powerful profit center was cemented by a key Skilling decision. Pai had originally been in charge of the financial traders, a small portion of the trading business.

28/ "Skilling expanded his purview to include traders who handled the logistics of moving gas through pipelines for physical delivery. They were now responsible for getting gas to customers and managing price risk from long-term sales contracts that Enron’s marketers negotiated.

29/ "This gave Pai and his traders a wealth of intelligence about what was going on in the marketplace, information no other company’s trading desk could match.

"It was the marketing originators who got all the glory. Whenever ECT signed a long-term contract with a customer,

"It was the marketing originators who got all the glory. Whenever ECT signed a long-term contract with a customer,

30/ "it could immediately declare the profits for the entire deal on its income statement, thanks to mark-to-market accounting. In addition, Ken Lay’s strategic goal was to create new markets for natural gas, and that’s precisely what these originators did with their deals.

31/ "For years, Sithe helped Enron meet its aggressive profit targets. Using mark-to-market accounting, Enron began booking profits even before the plant started operating. It kept booking profits from Sithe well into the late 1990s

32/ "by restructuring the deal on multiple occasions when the company was scrambling to meet its quarterly projections. Later, the deal’s complex machinations backfired, producing a huge liability that Enron never fully disclosed. But that was far in the future." (p. 113)

33/ "There was no NYMEX futures market beyond 18 months. Prices for 20-year deals like Sithe were set by deploying models and plotting curves, models and curves that were, at best, educated guesswork and, thanks to Pai’s clout, set at the discretion of the trading desk." (p. 115)

34/ "One thing developing nations needed was cheap, plentiful, reliable energy. If they hoped to lure other forms of development or provide for growing populations, they needed energy before just about anything else, which meant more pipelines, more power plants, more everything.

35/ "In the early 1990s, Enron predicted that worldwide power plant requirements would grow by 560,000 MW over the next decade. Government agencies were willing to loan to fund big energy projects, as were big banks, so companies like Enron had to invest only a tiny sliver.

36/ "Wall Street analysts talked about the potential for 30% returns on equity, triple what U.S. pipelines earned. Companies raced in to stake their claims. The projects were massive.

"In 1996, two dozen foreign companies bid on Bolivia's state oil and gas company.

"In 1996, two dozen foreign companies bid on Bolivia's state oil and gas company.

37/ "The winning company took the initial up-front risk, with plans to extract quick profits by selling off pieces to other buyers once the project was under way. That plan was predicated on the belief that someone else would always be willing to pay a higher price." (p. 133)

38/ "While Enron International executives loved putting deals together, the business had a flaw endemic to Enron: no one felt responsible for actually managing the projects.

"Because the developers were trying to do so many deals, Enron got a reputation for dropping the ball.

"Because the developers were trying to do so many deals, Enron got a reputation for dropping the ball.

39/ "Among the developers, a belief took hold that the time it took to manage expenses just wasn’t worth it. No one ever thought about how to pay for it all.

"The money Enron poured into projects that never were built—tens of millions each deal—was supposed to be written off.

"The money Enron poured into projects that never were built—tens of millions each deal—was supposed to be written off.

40/ "Yet Enron International often booked such costs as an _asset_ on the balance sheet in what came to be known around the company as “the snowball.” Usually the rationale was that there was no official letter saying the project was dead, so therefore, officially, it wasn’t.

41/ "Rich Kinder had a rule: the snowball had to stay <$90 million. But it eventually ballooned to over $200 million.

"The assumptions Enron made to justify its deals assumed nothing would ever go wrong. Of course, the banks financing the deals were making the same assumption.

"The assumptions Enron made to justify its deals assumed nothing would ever go wrong. Of course, the banks financing the deals were making the same assumption.

42/ "This was a mania, after all. But building energy projects in poor countries—often run by dictators and where capitalism was still a new concept—was absolutely fraught with peril, and it was absurd to believe that everything would play out according to plan.

43/ "Rebecca Mark’s inherent optimism led her to push forward where others might have at least hesitated. Over time, naysayers in her operation were relegated to lesser roles. People who worked for her say she trusted her gut far more than any spreadsheet." (p. 137)

44/ "Developers had no financial incentive to follow through on deals they’d just completed.

"If the developers estimated that a project would ultimately bring Enron $100 million, the developers took home $9 million up front. The system encouraged them to gamble.

"If the developers estimated that a project would ultimately bring Enron $100 million, the developers took home $9 million up front. The system encouraged them to gamble.

45/ "But it was operating projects that produced the real money. (Around 1994, this changed: developers were paid 50% at the close, the rest once the project was operational.)

"The board loved the idea that Enron was providing power to people who desperately needed it." (p. 139)

"The board loved the idea that Enron was providing power to people who desperately needed it." (p. 139)

46/ "One executive remembers a conference call between Mark and Ken Lay to discuss Mark’s bonus for Dabhol. The cash-flow estimates she had prepared assumed, naturally, that everything would go smoothly, but Lay offered no objections to her spreadsheet." (p. 145)

47/ "The community of Wall Street analysts and institutional investors that followed the energy industry was enthralled with the company and rewarded Enron the only way it knew how: by buying the stock." (p. 147)

48/ "Just as Lay wanted Enron employees to see him as the keeper of Enron’s “vision and values... respect, treating other people the way we want to be treated ourselves; absolute integrity, we’re honest, we’re sincere, we mean what we say, we say what we do. . . .”

49/ In one memo sent to staff, he wrote, “As a partner in the communities in which we operate, Enron has a responsibility to conduct itself according to basic tenets of human behavior that transcend industries, cultures, economics, and local, regional and national boundaries.”

50/ "Both Lay and his children used company’s fleet of airplanes for private purposes. Linda Lay used an Enron plane to visit her daughter Robyn in France. Another time, an Enron jet was dispatched to Monaco to deliver Robyn’s bed." (p. 153)

51/ "Enron began turning to aggressive accounting tactics. The things it did were not illegal, nor did they push the boundaries anywhere near as far as later in the decade. But they did help mask unpleasant financial realities and pushed the company into accounting’s gray zone.

52/ "Kinder had a sense of where the limits were—he knew how to maintain control. Had he stayed, Enron’s highs would never have been as high. But the lows would never have been as low.

"Enron was promising investors that its earnings per share would grow at 15% a year." (p. 157)

"Enron was promising investors that its earnings per share would grow at 15% a year." (p. 157)

53/ "The bull market of the 1990s was an era when growth companies were the only kind of companies investors wanted to buy.

"Every company, it seemed, was striving to become known as a growth company.

"Every company, it seemed, was striving to become known as a growth company.

54/ "The problem is that when a growth company announces earnings that don’t meet the aggressive target it has set for itself, the punishment is severe. Growth stocks can run up when the news is good, but they can spiral downward just as quickly when the news is bad." (p. 157)

55/ "Enron reworked long-term supply contracts, which would then allow it to post additional earnings due to MTM accounting. The company sold assets and made other nonrecurring moves, but it didn’t always label these as nonrecurring; it declared them part of ongoing operations.

56/ "For anyone willing to wade through the company’s financial documents, the numbers were clear.

"Hurt noted that when you stripped a few onetime gains out of Enron’s seemingly healthy 1995 earnings, including the profit Enron recorded for selling shares of Enron Oil and Gas,

"Hurt noted that when you stripped a few onetime gains out of Enron’s seemingly healthy 1995 earnings, including the profit Enron recorded for selling shares of Enron Oil and Gas,

57/ "1995 hadn’t been such a good year after all. Without those gains, Enron’s profits actually fell. But stories like that were soon forgotten." (p. 159)

"Just about every member of the board seemed to believe that Ken Lay walked on water.

"Just about every member of the board seemed to believe that Ken Lay walked on water.

58/ "The Great Man persona he presented to the world at large was also what the Enron directors saw. To their way of thinking, Ken Lay was the one indispensable person at Enron. The flavor of the board meetings only reinforced the notion that all was perfect at Enron." (p. 162)

59/ " “It was a recipe for disaster,” says an early ECT executive. “You had Lay, who was disengaged, and Skilling, who was a big-picture guy & a terrible manager.” There were many Enron executives, even at the time, who felt that Skilling was miscast in Kinder’s old job." (p.169)

60/ " “One of the biggest concerns consistently voiced about Enron is the complexity of its operations and how those interrelationships affect the quality of its earnings,” wrote a Morgan Stanley analyst in the spring of 1997.

61/ "When investors are in love with a stock, they forgive a lot. Analysts ignore potential problems and accept management’s word that a nonrecurring charge not part of the ordinary course of business. They work to put a positive gloss on the most ho-hum corporate announcements.

62/ "But when Wall Street goes negative on a stock, the opposite phenomenon takes place: a remorseless skepticism takes hold, as investors search for clues that more bad news is on the way. Such was the case with Enron as Skilling took over as president." (p. 170)

63/ "By 1995, the spot-market price had dropped far below what Enron had agreed to pay. That meant it was no longer possible to sell the gas at a profit.

"Enron had numerous chances to sell the J-Block gas at about the price it had committed to pay.

"Enron had numerous chances to sell the J-Block gas at about the price it had committed to pay.

64/ "Kelly's successors turned down the suitors, holding out hope that the market would climb, allowing them to book a profit.

"By 1995, Enron’s exposure approached $2 billion at a time when Enron’s total market value was $5 billion. J-Block posed a threat to Enron’s survival.

"By 1995, Enron’s exposure approached $2 billion at a time when Enron’s total market value was $5 billion. J-Block posed a threat to Enron’s survival.

65/ "Enron insisted that it did not expect the contract to have a “materially adverse effect on its financial position.” London-based insiders shook their heads at this. In their newly skeptical mode, securities analysts who followed Enron weren’t buying it either." (p. 172)

66/ "Under the new law partially deregulating the industry, utilities were supposed to make their transmission lines available to anyone, much as natural-gas pipeline companies had been required to provide open access. This was critical to making electricity trading profitable.

67/ "Enron might want to buy cheap power from underused plants in balmy New England and move it to sweltering Florida for sale at higher prices. But the logistics of moving power were incredibly complex, and the utilities, unhappy about the new law, threw up roadblocks.

68/ "States had enormous regulatory power, and most were less eager to deregulate than the federal government. Through their access to the nationwide electric grid, utilities could tell instantly when a plant anywhere in the country had gone down, a move that might spike prices.

69/ "They had precisely the kind of information advantage Enron had in natural gas. And there was one more big difference between the two businesses: unlike gas, electric power can’t be stored. This meant that electricity prices were far more volatile than for natural gas.

70/ "So Skilling went in another direction: he decided to buy his way into the club by having Enron purchase a utility.

"To get the utility to agree to a buyout, Enron offered a price a 46% premium to its market price. (Enron stock dropped nearly 5% on the news.)

"To get the utility to agree to a buyout, Enron offered a price a 46% premium to its market price. (Enron stock dropped nearly 5% on the news.)

71/ "That was yet another difference between Skilling and Kinder: once Skilling got his eye on the prize, price was no object. He believed that the business he would build with the asset would make so much money that it didn’t matter if he overspent in the beginning." (p. 177)

72/ "Skilling thought he had it down to a formula: Enron would buy the infrastructure needed to crack the code, build a new trading business—and then unload the assets when everybody else started to pile in." (p. 181)

73/ "Skilling turned Enron into a place where financial deception became almost inevitable, partly because there were so many other kinds of deception taking place. Skilling created a freewheeling culture he touted as innovative but didn’t rein in the excesses that came with it.

74/ "He claimed intellectual capital was critically important to give smart people the freedom to let creativity flourish but looked the other way when this became a license for wastefulness. He bragged about Enron’s sophisticated controls but undermined them at every turn.

75/ "He was scornful of asset-based businesses that grew slowly but generated cash—then swept them away to make room for ever-bigger, ever-riskier bets that brought in almost no cash. He created impossible expectations by holding Enron out to Wall Street as something it wasn’t.

76/ "He created a wild experiment, yet presented it as a well-oiled machine that generated steadily growing profits. The Enron Skilling was describing—and which by 1998 Wall Street and the press were once again lapping up—wasn’t even close to reality." (p. 187)

77/ "Enron claimed its risk systems were so good that there was no need to slow the frantic pace of deal making.

"It is business wisdom that many of a company’s best deals are the ones it doesn’t do. That was never the belief at Enron, a place that was defined by deal making.

"It is business wisdom that many of a company’s best deals are the ones it doesn’t do. That was never the belief at Enron, a place that was defined by deal making.

78/ “The corporate culture was such that you never said no to a deal.”

"Deal makers were often allowed to set absurdly optimistic assumptions for the complex models that spat out the likelihood of various outcomes for a transaction.

"Deal makers were often allowed to set absurdly optimistic assumptions for the complex models that spat out the likelihood of various outcomes for a transaction.

79/ "Incredibly, traders and originators sat on panels that ranked the same RAC executives who reviewed their transactions. Everyone was supposed to act honorably, but there were clear opportunities for retaliation." (p. 191)

80/ "Skilling might say he was going to hold deal makers responsible, but he rarely did, and the deal makers all knew it. On the contrary, by the time it was clear that the deal had gone south, the originator would have gotten his bonus and moved on." (p. 192)

81/ "The dot-coms, too, had newfangled cultures, which featured spending without controls and strategies that changed on the fly. Everybody talked about moving at Internet speed. Skilling positioned Enron as a company that had more in common with the dot-coms than with Exxon.

82/ "No one suspended disbelief more than Skilling himself: he seems to have truly thought the culture he was establishing would give Enron a huge competitive advantage. But to many on the inside, the new Enron culture made it, quite simply, an unpleasant place to work." (p. 197)

83/ "The stock became Enron’s obsession. A ticker in the lobby offered a constant update. TV monitors broadcast CNBC in the elevators. Employees were repeatedly encouraged to buy Enron shares; on average, they kept more than half their 401(k) retirement holdings in Enron shares

84/ "In 1998, when the stock price hit $50, Skilling and Lay treated it as a major corporate milestone, handing out $50 bills to every Enron employee.

"Eventually, he would justify business decisions entirely on the basis of what it would mean to Enron’s valuation.

"Eventually, he would justify business decisions entirely on the basis of what it would mean to Enron’s valuation.

85/ ""There was nothing at Enron that required more effort, more cleverness, more deceit—more everything—than hitting its quarterly earnings targets.

"But a company built around trading and deal making cannot possibly count on steadily increasing earnings.

"But a company built around trading and deal making cannot possibly count on steadily increasing earnings.

86/ "Because of volatile earnings, companies whose business is primarily trading have low stock valuations. Goldman Sachs, widely viewed as the best trading firm in the world, has a P/E that rarely goes above 20x. It never even attempts to predict its earnings ahead of time.

87/ "Enron’s valuation was twice that by the late 1990s, and Skilling wanted it higher. So instead of admitting that Enron was engaged in speculation, he claimed it was a logistics company, which found the most cost-effective way to deliver power from any plant to any customer.

88/ "The Enron trading desk, Skilling added, always had a matched book—meaning that every short precisely offset every long—and made its money merely on commissions. Right up to the end, Skilling & his lieutenants stuck to that line, long after it had become demonstrably false.

89/ "He would openly ask the stock analysts: “What earnings do you need to keep our stock price up?” And the number he arrived at was the number Wall Street was looking for, regardless of whether internally it made any sense." (p. 203)

90/ "Deal closings were accelerated so that earnings could be posted by the end of the quarter. This usually required capitulating on key negotiating points.

"By 1997, Enron had extended mark-to-market accounting to every portion of its merchant business.

"By 1997, Enron had extended mark-to-market accounting to every portion of its merchant business.

91/ "It used MTM to book profits on private equity and venture-capital investments, where values were extraordinarily subjective.

"Deal makers regularly revisited large existing contracts—some more than 5 years old—to see if they could squeeze out a few million more in earnings.

"Deal makers regularly revisited large existing contracts—some more than 5 years old—to see if they could squeeze out a few million more in earnings.

92/ "Contracts were restructured/renegotiated or reinterpreted in ways to make them appear more profitable.

"Other tricks included delays in recording losses & generating earnings through tax-avoidance schemes.

"All this rolled Enron's problems further into the future." (p.206)

"Other tricks included delays in recording losses & generating earnings through tax-avoidance schemes.

"All this rolled Enron's problems further into the future." (p.206)

93/ "Enron carried Mariner on its books throughout this period for about $365 million; its own internal-control group placed its value in a broad range between $47 million and $196 million." (p. 208)

94/ "Eventually, the whole thing took on a life of its own, with an insane logic that no one at the company dared contemplate: to a staggering degree, Enron’s “profits” and “cash flow” were the result of the company’s own complex dealings with itself." (p. 214)

95/ "While people at Enron were good at bending rules, they were not smart about understanding where it was taking them." (p. 227)

"Accountants in Arthur Andersen’s Houston office worked so closely with Enron that they came to see the world in the same way as Enron executives.

"Accountants in Arthur Andersen’s Houston office worked so closely with Enron that they came to see the world in the same way as Enron executives.

96/ " Nor did they want to risk losing one of their biggest clients. This was part of the modern bull market: a gradual disintegration of accountings high standards." (p. 227)

"When Anderson did object to an Enron transaction, Enron put the firm under intense pressure." (p. 233)

"When Anderson did object to an Enron transaction, Enron put the firm under intense pressure." (p. 233)

97/ "Enron continued to fund its growth—billions of dollars each year—through the miracle of structured finance. Structured finance enabled Enron to raise capital off its balance sheet to an extent no one imagined possible without adding debt or issuing stock." (p. 238)

98/ "Many of the entities Enron created to play its financial games were not only revealed in the company’s publicly filed financial documents but were things Fastow was happy to boast about. Wall Street analysts often mentioned the company’s “innovative” financing tools.

99/ "Credit-rating agencies knew about much of Enron’s off-balance-sheet debt. But there were other deals in which the circle of outsiders in the know was small—& the disclosure in Enron’s financial documents was purposely vague—as real disclosure would raise too many questions.

100/ "Finally, there were deep, dark secrets that no one knew about except Fastow and his closest associates.

"These were intended to allow Enron to borrow the billions of dollars that it needed to keep itself going while disguising the true extent of its indebtedness." (p. 244)

"These were intended to allow Enron to borrow the billions of dollars that it needed to keep itself going while disguising the true extent of its indebtedness." (p. 244)

101/ "Enron stock supported a pool of debt that was being used to buy Enron’s assets and create cash flow.... impossibly circular logic." (p. 245)

"Securitization, at least the way Enron did it, provided a great short-term boost.

"Securitization, at least the way Enron did it, provided a great short-term boost.

102/ "But as with so many Enron deals, it created ticking time bombs of debt that was rarely supported by the true value of the asset: it was often based on unreasonably optimistic assumptions. It was a purported sale, but it looked and smelled like a financing." (p. 247)

103/ "By the end, Enron owed $38 billion, of which only $13 billion was on its balance sheet. Fastow’s team never added it all up, though that’s what responsible finance executives are supposed to do. Indeed, they thought their work was helping the company." (p. 251)

104/ "Fastow's group could not have done what they did without help. They needed accountants to agree prepays were a trading liability. They needed lawyers to sign off on deal structures. They needed credit-rating agencies to remain sanguine in the face of off-balance-sheet debt.

105/ "Most of all, though, they needed the banks & investment banks. Every bit as much as the accountants at Arthur Andersen, the banks and investment banks were Enron’s enablers.

"By the late 1990s, Enron was one of the largest payers of investment banking fees in the world.

"By the late 1990s, Enron was one of the largest payers of investment banking fees in the world.

106/ "The increased competition for investment banking fees made the banks practically desperate to land business. Objectively, the party that should have felt desperate was Enron; it needed a steady infusion of capital just to keep operating.

107/ "But there were so many banks clamoring for Enron fees that Fastow could keep them on a string by playing them off against each other.

"Investment bankers tend to think they’re smarter than the company executives they’re advising, but they didn’t feel that way about Enron.

"Investment bankers tend to think they’re smarter than the company executives they’re advising, but they didn’t feel that way about Enron.

108/ "Global Finance executives acted just like investment bankers. They spoke the same language.

“In investment banking, the ethic is, ‘Can this deal get done?’ ” says a banker. “If it can and you’re not likely to get sued, then it’s a good deal.” " (p. 255)

“In investment banking, the ethic is, ‘Can this deal get done?’ ” says a banker. “If it can and you’re not likely to get sued, then it’s a good deal.” " (p. 255)

109/ "There were whispers in the banking world that Enron consumed incredible amounts of capital, that the company was way overleveraged, that, as one internal Citigroup e-mail explicitly put it, “Enron significantly dresses up its balance sheet for year-end.” " (p. 258)

110/ "Providing electricity and gas at a discount to customers was a money-loser because most states were still refusing to deregulate retail energy. The only way Enron could cut the cost of energy for a customer was to buy electricity from a local utility & resell it at a loss.

111/ "Enron did it because it remained convinced—despite evidence to the contrary—that the states would soon open up their markets and the company would make money at the tail end of long-term contracts.

"By 2001, only a quarter of the U.S. power market had opened up." (p. 274)

"By 2001, only a quarter of the U.S. power market had opened up." (p. 274)

112/ "Enron was promising to run the cooling and heating systems, hire the energy-maintenance staff, change the lightbulbs, and pay the bills. Enron had never shown that it could manage that sort of operation.

113/ "Just as the new dot-coms had such uneconomic measures as “eyeballs” and “hits,” Enron now had Total Contract Value, which gave Wall Street something to focus on besides profits." (p. 274)

114/ "Analysts beheld the picture of a booming business: a big open room, bustling with people, busily working telephones & hunched over computer terminals, cutting deals and trading energy. Giant plasma screens displayed electronic maps. Commodity prices danced across a ticker.

115/ " “It was impressive, a veritable beehive of activity,” recalls analyst John Olson, who'd covered the company for Merrill Lynch. It was also a sham. Though EES was just gearing up, Skilling and Pai had staged it to convince their visitors that things were already hopping.

116/ "On the day the analysts arrived, the room was filled with Enron employees. Many didn’t even work on the sixth floor. They were secretaries, EES staff from other locations, and non-EES employees drafted for the occasion and coached on the importance of appearing busy.

117/ "An administrative assistant recalls being told to bring her personal photos to make it look as if she actually worked at the desk where she was sitting; she spent most of the time talking to her girlfriends on the phone.

118/ "After getting the all-clear signal, Garcia returned to her real desk on the ninth floor. The analysts had no clue they’d been hoodwinked.

"EES executives reasoned that this deception wasn’t a problem. Eventually, EES really would use all that space." (p. 277)

"EES executives reasoned that this deception wasn’t a problem. Eventually, EES really would use all that space." (p. 277)

119/ "The EES originators—they eventually totaled 170—got huge bonuses not on the basis of how a deal worked out over time but on how profitable it appeared on the day the contract was signed.

"They used the standard Enron tricks to make their deals look better than they were.

"They used the standard Enron tricks to make their deals look better than they were.

120/ "Even though state deregulation was stalled, they priced contracts as if it were inevitable. They signed 15-year contracts that even they acknowledged would lose money for the first ten years but included a wildly optimistic price curve that showed steep profits at the end.

121/ "They underestimated the cost of and overestimated savings from efficiency improvements. They stomped all over Rick Buy’s risk assessors.

"Different parts of Enron made different long-term pricing assumptions, then booked MTM profits based on incompatible guesses." (p. 279)

"Different parts of Enron made different long-term pricing assumptions, then booked MTM profits based on incompatible guesses." (p. 279)

122/ "EES would have to pay the cost to fulfill its contracts someday. The sales team, paid up front, wasn’t worried. One senior sales executive joked that he’d close deals, then “throw them over the fence” to let the back-office staff worry about making them work." (p. 280)

123/ "Lacking implementation expertise, Enron acquired energy-management and facilities companies.

"Promised energy-saving projects were never started, unpaid utility bills piled up, and EES tried to wiggle out of agreements that were too difficult or too expensive." (p. 281)

"Promised energy-saving projects were never started, unpaid utility bills piled up, and EES tried to wiggle out of agreements that were too difficult or too expensive." (p. 281)

124/ "To get Enron an Internet-style valuation, Skilling had to convince Wall Street that Enron was becoming an Internet company.

"Enron claimed that its system would transform the Internet by providing bandwidth and switching capacity to distribute TV-quality video.

"Enron claimed that its system would transform the Internet by providing bandwidth and switching capacity to distribute TV-quality video.

125/ "It would create a market in bandwidth trading, then take that market to critical mass in the span of just two years. Enron had a team working to develop content and to figure out how to send high-quality entertainment & other video over the Internet with no delay." (p. 288)

126/ "But in the here and now, EES and broadband had chewed up capital while generating little cash." (p. 289)

"Every high-level Enron executive held options worth millions. There was even a long-term incentive plan to provide yet another payoff built on Enron’s share price.

"Every high-level Enron executive held options worth millions. There was even a long-term incentive plan to provide yet another payoff built on Enron’s share price.

127/ "As Enron’s finance executives realized the company was still short of its earnings targets, it undertook two deals that were egregious even by Enron’s standards. Both involved Merrill Lynch; it wasn’t lost on anyone that Merrill was helping Fastow raise money for LJM2.

128/ "Schuyler Tilney and Rob Furst explained to a firm committee reviewing the deal that it presented no risk to Merrill and that they had extracted the oversize $17 million profit because Enron was desperate to hit its Wall Street targets.

129/ "One Merrill executive, according to a later SEC complaint in the matter, expressed reservations: wasn’t this earnings manipulation? Merrill, responded a senior executive, has “17 million reasons” for doing the deal.

130/ "Ultimately, they agreed to split the difference: in June, Enron paid Merrill $8.5 million for its help in manufacturing earnings. Arthur Andersen never followed through on its threat to force Enron to restate the $50 million if the trades were later unwound." (p. 315)

131/ "Enron’s traders violated trading limits frequently with no meaningful consequences." (p. 331)

"One of Enron’s key advantages was information. Its physical assets provided information, of course. It also employed former CIA agents who could find out anything about anyone.

"One of Enron’s key advantages was information. Its physical assets provided information, of course. It also employed former CIA agents who could find out anything about anyone.

132/ "Instead of tracking the weather on the Weather Channel, the company had a meteorologist on staff. Enron employees paid farmers located near power plants to let them put cameras on fences to monitor activity.

133/ "Once, the company sent an analyst to pose as a porta-potty salesman. His task was to figure out how long a plant was supposed to be under construction so the traders could learn when it might start producing power.

134/ "Enron sent analysts to meetings of the Washington State’s electric commission, where policy makers talked about the level of water in various dams. When the level was high, that meant there was plenty of hydroelectric power, so the traders might short electricity." (p. 333)

135/ "There was one difference between Enron Online and, say, the New York Stock Exchange: the stock exchange wasn’t controlled by one important market participant, like Merrill Lynch or Goldman Sachs. With Enron Online, Enron controlled the energy exchange completely." (p. 334)

136/ "Anyone who used the EOL system could trade only with Enron. It would serve as the counterparty for every single trade: Enron would know what each of its competitors was doing.

"EOL was a brilliant innovation but had a hidden cost. Because Enron was involved in every trade,

"EOL was a brilliant innovation but had a hidden cost. Because Enron was involved in every trade,

137/ "it dramatically increased the capital requirements of the trading business. Just how dangerous this was would become all too apparent—much later. But at the time, because Enron could trumpet EOL as part of its embrace of the Internet, it helped the stock." (p. 336)

138/ "EOL made Enron as close to omniscient as any traders have ever been or ever will be again.

"Competitors worried that Enron could effectively determine prices for certain energy contracts, especially those that were thinly traded." (p. 337)

"Competitors worried that Enron could effectively determine prices for certain energy contracts, especially those that were thinly traded." (p. 337)

139/ "Even though trading was enormously volatile, Skilling expected the traders to generate steadily increasing earnings every year. Vince Kaminski, Enron’s probability guru, used to warn Skilling that in any given year, profits were as likely to go down as to go up." (p. 343)

140/ "At the tail end of a bull market that had run for a decade, any company with a flashy stock chart and an eye-popping P/E ratio took on an aura of invincibility. “Enron is literally unbeatable at what they do,” raved David Fleischer, a securities analyst at Goldman Sachs.

141/ " “The industry standard for excellence,” chimed in Deutsche Bank’s Edward Tirello. “Enron is the one to emulate,” wrote the Financial Times. Any remaining vestiges of skepticism were washed away in the torrent of praise that showered over the company and its top executives.

142/ "Enron’s nearly incomprehensible financial statements? Nobody worried about them. The related-party transactions buried in the footnotes? Who bothered with footnotes? That Skilling sometimes seemed unable to give a coherent explanation of Enron’s business bothered no one.

143/ "All that mattered was that the stock was going up. Because the stock was rising, Enron’s executives were seen as brilliant.

"Because the market rewarded every new move they made, Enron’s employees started to think they couldn’t make mistakes.

"Because the market rewarded every new move they made, Enron’s employees started to think they couldn’t make mistakes.

144/ "Enron was hardly the only company to see its stock ascend on a cloud of hype as the 1990s came to a close. But it was different in one critical way: the circle of people who should have known that Enron’s glittering surface masked a different reality was surprisingly large.

145/ "Much of what Enron did—e.g., generating billions in off-balance-sheet debt—was in the open. Analysts knew the company’s earnings far outstripped cash coming in. Investment bankers, who worked for the same firms as the analysts, understood; they made Fastow’s deals possible.

146/ "The credit-rating agencies knew a lot. The business press, which could have looked more closely at Enron’s financial statements, couldn’t be bothered; the media was utterly captivated by the company’s transformation from stodgy pipeline to new economy powerhouse." (p. 346)

147/ "Analysts got to be rich and famous only if they were bullish. That’s what got them appearances on CNBC.

"As the market rocketed upward, bearish analysts put their jobs in jeopardy. In Internet chat rooms, investors flamed analysts who downgraded their favorite stocks.

"As the market rocketed upward, bearish analysts put their jobs in jeopardy. In Internet chat rooms, investors flamed analysts who downgraded their favorite stocks.

148/ "Even sophisticated institutional investors—the analysts’ primary clients—often became angry at research analysts who turned bearish on stocks they held. It didn’t matter if the analyst was correct or perceptive; all that mattered was that he or she had hurt the stock.

149/ "In truth, many Wall Street researchers had largely stopped doing anything that resembled serious securities analysis.

"The modern analyst was more a marketer than a researcher and was consumed by short-term considerations. Above all else, analysts focused on earnings.

"The modern analyst was more a marketer than a researcher and was consumed by short-term considerations. Above all else, analysts focused on earnings.

150/ "They regularly consulted with the company’s investor relations executives for earnings guidance.

"So long as a company met or beat its EPS estimate, nothing else mattered. Cash didn’t matter. Off-balance-sheet debt didn’t matter. Even on-balance-sheet debt didn’t matter.

"So long as a company met or beat its EPS estimate, nothing else mattered. Cash didn’t matter. Off-balance-sheet debt didn’t matter. Even on-balance-sheet debt didn’t matter.

151/ "In the bull market, no analyst was going to spoil the party by asking tough questions about how it had pulled this off.

"Launer was a longtime, well-respected natural-gas analyst. But by the late 1990s, his career became an example of rewards that came with the new rules.

"Launer was a longtime, well-respected natural-gas analyst. But by the late 1990s, his career became an example of rewards that came with the new rules.

152/ "In his reports, he didn’t seem to have particularly deep insights. Some at the company didn’t think much of him. “He loved going to lunch with Skilling & Lay. He was never into the numbers. He didn’t understand the trading business even after we spent years explaining it.”

153/ "But he pounded the table for a soaring stock. In both 1998 and 1999, Launer was named Institutional Investor magazine’s #1–rated natural-gas analyst, largely on the strength of his “longstanding buy signal on Enron.” #1 analysts tended to make $1 million a year or more.

154/ "Momentum investors don’t stick around. Just as they can help drive a stock higher, they can also accelerate a downward push. But convinced that Enron’s stock would never go down, neither Skilling nor Lay was worried about the influx of momentum players." (p. 350)

155/ "The Enron story, when Skilling told it, sounded so good; otherwise intelligent people were reduced to nodding their heads in agreement. Skilling listened to what the market wanted and sold Enron that way.

156/ "There was simply too much investment-banking business at stake not to have a screaming buy on the stock. The more banking business a company did, the more leverage it had over the analysts who covered it." (p. 351)

157/ "Because a downgrade can have such dire consequences, the credit rating agencies are often slow to act, critics say; many times, the market passes judgment long before the rating agencies do.

"Enron's credit rating was the lifeblood of its trading business.

"Enron's credit rating was the lifeblood of its trading business.

158/ "All counterparties were, in effect, accepting Enron's credit. If you enter into a ten-year swap, you want to know that company is going to be around. It is impossible to operate a trading business without an investment-grade credit due to collateral requirements." (p. 355)

159/ "Even as Enron’s debt ballooned, as the related-party disclosures in its financial statements grew longer and more incomprehensible, as the numbers got bigger, as more and more profits came from the inherently volatile trading operation, the agencies didn’t sound the alarm.

160/ "While the credit analysts saw many of the pieces that made up Enron’s convoluted financing, they never added them all up and never realized how precarious it was. Instead of acting as the ultimate watchdog, the credit analysts unwittingly provided false sense of security.

161/ "Stock analysts and investors alike took solace in the fact that the credit analysts gave Enron an investment-grade rating. After all, credit analysts had access to more information than equity analysts, so surely there was nothing to worry about." (p. 358)

162/ "Like most Wall Street frenzies, the international development craze was wildly overhyped. In the wake of the Asian crisis of 1998 and the resulting economic meltdown in emerging markets, the values of virtually all energy assets collapsed—it didn’t matter who owned them.

163/ "Even so, some of Enron International’s assets were comically awful. A power plant it built in China was never commercially operated. The Dominican Republic plant was padlocked for a time. The plant in Cuiabá, Brazil, was hundreds of millions of dollars over budget.

164/ "In Poland, there were difficulties getting the government to pay Enron for a plant it had built. A planned pipeline in Mozambique never happened, nor did a $500M plant in Indonesia or a $200M plant in Croatia. The $3B Dabhol project remains shuttered to this day." (p. 386)

165/ "Whalley’s position was that it wasn’t Enron that was at fault; the problem was the foolishness of the rules, which were so easy to take advantage of.

"It seems that Enron traders simply didn’t believe any outsider would ever be smart enough to connect the dots." (p. 402)

"It seems that Enron traders simply didn’t believe any outsider would ever be smart enough to connect the dots." (p. 402)

166/ "The FERC estimated that Enron earned a mere $60 million from “congestion revenues” and that it was “highly unlikely” that the impact of Belden’s strategies on spot prices “accounted for a substantial portion of Enron’s total revenues.”

167/ "But, the ISO noted, it is impossible to gauge the “indirect impact on overall market outcomes.”

"But the company was making a fortune in its long position. Enron executives, knowing how poorly that would play, were desperate to avoid disclosing the figures." (p. 407)

"But the company was making a fortune in its long position. Enron executives, knowing how poorly that would play, were desperate to avoid disclosing the figures." (p. 407)

168/ "After Enron collapsed, the FERC, while still blaming a “supply shortfall and a fatally flawed market design,” also agreed with many of California’s allegations, arguing that there was “evidence of market manipulation” on the part of many of the big energy traders." (p. 414)

169/ "Enron couldn’t back away from Skilling’s profit predictions without causing the stock to crater. So the broadband executives would have to build a new industry from scratch in a short time. In the meantime, they'd create a portrait of a reality that didn’t exist." (p. 422)

170/ "The Enron network couldn’t provide bandwidth-on-demand and never would. The switching capability was still under development, as were other advanced features of Enron’s system. Yet Enron continued to portray most of its key components as present-day reality.

171/ "During 2000, top broadband executives regularly discussed among themselves the Enron network’s inability to do much of what the company claimed. Still, Enron kept issuing fresh press releases boasting about network capabilities that didn’t exist." (p. 423)

172/ "Enron was hardly the only company trying to build a huge network of high-speed fiber-optic cable. During the Internet bubble, dozens of start-ups had sprung to life with this goal, and well-established companies had committed their own billions to building such networks.

173/ "As a result, there was a tremendous glut of fiber capacity, far outstripping the meager demand. Once the Internet bubble popped in the spring of 2000, prices plummeted. Soon enough, the entire telecom industry was in meltdown." (p. 426)

174/ "Skeptical voices that had been ignored during the great bull run were getting a hearing. And companies that hit or beat their earnings target could no longer be assured of a rising stock price. Investors were newly curious about how companies had arrived at those earnings.

175/ "They were digging deeper and asking questions. In the bull market, investors always saw the glass as half full; now, for the first time in years, they were seeing it as half empty. For all his brilliance, Skilling never seemed to understand this new dynamic.

176/ "He kept thinking that as long as Enron made its numbers, the stock would start climbing again. But he was wrong. It was short sellers who first asked tough questions about Enron. It was also triggered by Enron's use of mark-to-market accounting." (p. 467)

177/ "Jim Chanos's life changed forever when he began looking into a company called Baldwin United. Baldwin, which had been formed from the merger of a piano maker and an insurance company that sold annuities, was one of the hottest stocks of that era.

178/ "Chanos realized Baldwin was a giant Ponzi scheme that raised money secretly through subsidiaries, turned the money over to the parent to support enormous capital consumption, & used aggressive MTM assumptions on its portfolio of annuities to create fabulous earnings growth.

179/ "When it comes to stock-market frauds, history does repeat itself. In August 1982, the 24-year-old Chanos put out a sell report on Baldwin United. The report was extremely controversial, for Baldwin, just like Enron, had wide and vocal support among the analysts.

180/ "Merrill Lynch and many of the other firms made hefty commissions pushing Baldwin’s annuities on its retail customers. Chanos’s work was denounced up and down Wall Street. But by the fall of 1983, Baldwin had filed for bankruptcy." (p. 469)

181/ "The more Chanos poked around, the more he felt that the Enron story didn’t make sense. Chanos had made a fortune researching—then shorting—telecom stocks. He knew how much trouble they were in. How could Enron’s broad-band unit be doing so well?

182/ "Enron’s return on invested capital was abysmally low at 7%—and that figure didn’t even include the billions upon billions of off-balance-sheet debt.

"He was struck by a three-paragraph disclosure in Enron’s third-quarter 2000 filing about its dealings with a related party.

"He was struck by a three-paragraph disclosure in Enron’s third-quarter 2000 filing about its dealings with a related party.

183/ "No matter how many times he read it, he still couldn’t understand what it said. He showed it to derivatives specialists, corporate lawyers, and other experts; they couldn’t figure it out either.

"And then there were the insider sales by Lay and Skilling.

"And then there were the insider sales by Lay and Skilling.

184/ "Chanos and the others who shorted Enron’s stock didn’t have any special information that wasn’t available to the bulls. At first, “We didn’t think it was some great hidden fraud. We just thought it was a bad business.”

185/ "Enron was a speculative trading shop, which meant that, at an absolute minimum, its outsize P/E multiple made no sense. “You don’t give this a 50 multiple even if it’s the Goldman Sachs of the energy business.”

"While Enron’s reported earnings were growing smoothly,

"While Enron’s reported earnings were growing smoothly,

186/ "the business didn’t seem to be generating much cash—and you can’t run a business without cash. In fact, Enron had negative cash from its operations in the first nine months of 2000.

"There were other warning signs.

"There were other warning signs.

187/ "Enron’s debt was climbing—$3.9 billion added on the balance sheet in the first nine months of 2000 alone—which didn’t make sense if the business was as profitable as it claimed. It was also clear that Enron was selling assets and booking the proceeds as recurring earnings.

188/ "There was growing skepticism toward Enron in the investment community, though few were willing to express it on the record." (p.471)

"Investors complained to Enron’s investor-relations department that they didn’t want to hear excuses if they couldn’t see evidence." (p.479)

"Investors complained to Enron’s investor-relations department that they didn’t want to hear excuses if they couldn’t see evidence." (p.479)

189/ "In private deliberations in sequestered boardrooms, major institutions were reevaluating their positions on Enron. Unlike the public buy recommendations from the equity analysts, though, these private decisions never came to the attention of the small investor." (p. 496)

190/ "Lay’s finances were built around the belief that Enron’s stock would never go down. During most of the 1990s, Lay had most of his net worth in Enron stock. In 1999, his advisers began pestering him to diversify. But he did so in a manner that doubled his bet on the stock.

191/ "Lay pledged almost all of his portfolio of liquid assets—primarily Enron stock—as collateral for bank and brokerage loans.

"By early January 2001, Lay owed $95 million to creditors. Lay then used the money he had borrowed to make other investments.

"By early January 2001, Lay owed $95 million to creditors. Lay then used the money he had borrowed to make other investments.

192/ "Because so many of his investments—including three multimillion-dollar homes—were illiquid, Enron stock was the primary means to support his loans.

"In 2001, as Enron stock hit the $80 trigger & then the $60 trigger, Lay, just like his company, became desperate." (p. 501)

"In 2001, as Enron stock hit the $80 trigger & then the $60 trigger, Lay, just like his company, became desperate." (p. 501)

193/ "One of the subjects the board talked about were four new disaster scenarios Rick Buy and his risk-assessment group had put together at Skilling’s request. One scenario begins with the announcement that Enron would miss its earnings target, triggering a massive sell-off.

194/ "This leads to the collapse of the balance sheet because it forces the unwinding of all the off-balance-sheet vehicles that were capitalized with Enron stock, which prompts downgrades in credit ratings, which trigger the material adverse change clauses in trading contracts,

195/ "which cause its trading partners to start demanding that Enron post collateral. This wipes out Enron’s liquidity. But Skilling and Glisan dismissed the odds of this ever happening. Enron, the executives noted, had plenty of committed sources of emergency cash." (p. 505)

196/ "Enron’s “perception” problem evolved into a cash crisis. With Enron’s stock continuing to sink, panic took hold. The immediate problem was that Enron had been unable to roll its commercial paper—unsecured short-term loans that all big companies use to fund day-to-day needs.

197/ "Renewing such debt was normally routine. Though the amounts were huge (for Enron, $2 billion), the exposure was so brief (as little as 24 hours) that it was really nothing to worry about—unless lenders had reason to wonder if Enron would survive long enough to pay it back.

198/ "Enron needed money fast, before word trickled out & a rush of panicked creditors shut the company down.

"On Thursday, the company drew down the $3 billion in backup credit lines to its commercial paper. To Wall Street, this was instant confirmation of Enron’s desperation.

"On Thursday, the company drew down the $3 billion in backup credit lines to its commercial paper. To Wall Street, this was instant confirmation of Enron’s desperation.

199/ "Enron tried to cast this act of desperation as a strategic move, one intended “to dispel uncertainty in the financial community.” It was supposed to offer proof that the banks (which actually had no choice in the matter) were standing squarely behind the company." (p. 549)

200/ "With all the off-balance-sheet machinations, no one could immediately tell McMahon how much money Enron owed.

"Several of the deals had triggers requiring the immediate payback of debt if Enron’s share price fell below certain floors and its credit rating dropped too low.

"Several of the deals had triggers requiring the immediate payback of debt if Enron’s share price fell below certain floors and its credit rating dropped too low.

201/ "The stock price had already crashed through the floors; the challenge was to keep the credit ratings from dropping. After learning that Enron was drawing down credit lines, S&P changed Enron’s credit outlook—an interim step toward a ratings change—from stable to negative.

202/ "Fitch had already done the same. Moody’s had Enron’s rating under review. There was another frightening problem taking hold. A giant trading operation depends on credit to survive. This was especially true of Enron because of the giant cash needs of Enron Online.

203/ "Rating-agency downgrades—even just shattered confidence—would prompt trading partners to start demanding cash collateral, producing a run.

"As one Enron executive later put it: “Trading companies fall quickly—like a helicopter running out of fuel.” " (p. 550)

"As one Enron executive later put it: “Trading companies fall quickly—like a helicopter running out of fuel.” " (p. 550)

204/ "This time, Andersen resolved: no more games. Enron would need to restate its earnings all the way back to 1997, adding debt to its teetering balance sheet and wiping out a big chunk of its reported profits. This was horrible news for both Arthur Andersen and Enron." (p.556)

205/ "Despite all of Lay’s presumed clout, no one did anything meaningful to intervene. It seemed as though everyone was turning on Enron, even those that the company had always been able to manage—first Wall Street, then the media, now Washington." (p. 558)

206/ "In the thick of Enron’s crisis, some bankers were finally in the driver’s seat. They’d consider lending Enron money, but now it would be on their terms. At first, Enron didn’t fully appreciate how much things had changed.

207/ "Immediately after drawing down its backup credit lines, the company informed the banks it needed an extra $2 billion cash, at least. Enron executives still thought they could borrow the money unsecured as they always had. The banks flatly turned the company down.

208/ "J. P. Morgan Chase and Citi agreed to talk about lending an extra $1 billion, though Enron clearly needed much more. But now, they were demanding the only real collateral the company had left, the Transwestern and Northern Natural pipeline systems.

209/ "For years, Enron’s natural-gas pipelines had been an afterthought. Now they were the company’s lifeline. J. P. Morgan Chase and Citi also extracted commitments that Enron would use them exclusively for all its investment-banking work for the next 18 months." (p. 559)

210/ "No longer willing to trust Enron’s credit, more and more of the company’s trading counterparties were demanding cash collateral. Money was rushing out the door faster than Enron could raise it." (p. 565)

211/ "In its accounting work for Enron, Andersen had been sloppy and weak. But that’s how Enron had always wanted it. In truth, even as they angrily pointed fingers, the two deserved each other." (p. 569)

212/ "Enron announced its restatement, consolidating the troubled partnerships and rewriting more than four years of its accounting history. About $586 million in profits—20 percent of Enron’s previously reported net income dating back to 1997—was simply erased." (p. 569)

213/ "The list of those suing the company grew to include Enron’s own employees, who had seen much of their retirement-plan savings disappear. They claimed Enron’s top executives had misled them about the riskiness of Enron shares

214/ "and locked them into their plummeting holdings for a month while the company changed plan administrators. Between the company’s savings and stock-ownership plans—60% of the total assets in both consisted of Enron stock." (p. 579)

215/ "S&P downgraded Enron two notches, deep into junk-company territory, citing its “loss of confidence that the Dynegy merger will be consummated.” Moody’s and Fitch soon followed. The downgrades immediately triggered $3.9 billion in Enron debt." (p. 582)

216/ "December 2, was the day it finally happened. At 2 A. M., Enron’s lawyers filed the largest bankruptcy case in U.S. history. Just days before, everyone was focused on the Dynegy deal. Once that collapsed, bankruptcy was really Enron’s only alternative." (p. 585)

217/ "The analysts who had covered Enron—many of whom had buy recommendations on the stock right up until the end—claimed Enron had lied to them.

"The analysts for S&P and Moody’s insisted that the information they were given justified Enron’s investment-grade ratings.

"The analysts for S&P and Moody’s insisted that the information they were given justified Enron’s investment-grade ratings.

218/ "To be sure, Enron, with Andersen’s assistance, did everything it could to camouflage the truth, but there was more than enough on the public record to raise the hairs on the neck of any self-respecting analyst.

219/ "Analysts are supposed to dive into financial documents, pore over footnotes, get past management’s assurances & accounting obfuscations. If the analysts covering Enron had done that, how could they not have seen a very different story? The short sellers surely did." (p.588)

220/ "No matter whom you asked, it was always somebody else’s fault." (p. 589)

"After more than a decade, Enron’s thousands of unsecured creditors eventually received 53 cents on the dollar." (p. 591)

"After more than a decade, Enron’s thousands of unsecured creditors eventually received 53 cents on the dollar." (p. 591)

221/ "In the end, the Enron story will always be relevant: It’s a tale of human nature. Still, it’s hard not to wish for that naïve time when we really, truly thought that the act of putting Jeff Skilling and Ken Lay behind bars would solve everything." (p. 620)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh