Now that my monograph that I've worked on for the past years is finally out (and free for anyone to download!: brill.com/view/title/615…). I thought it would be nice to do a series of threads, writing accessible summaries on what my book is actually about. Today Chapter 1! 🧵

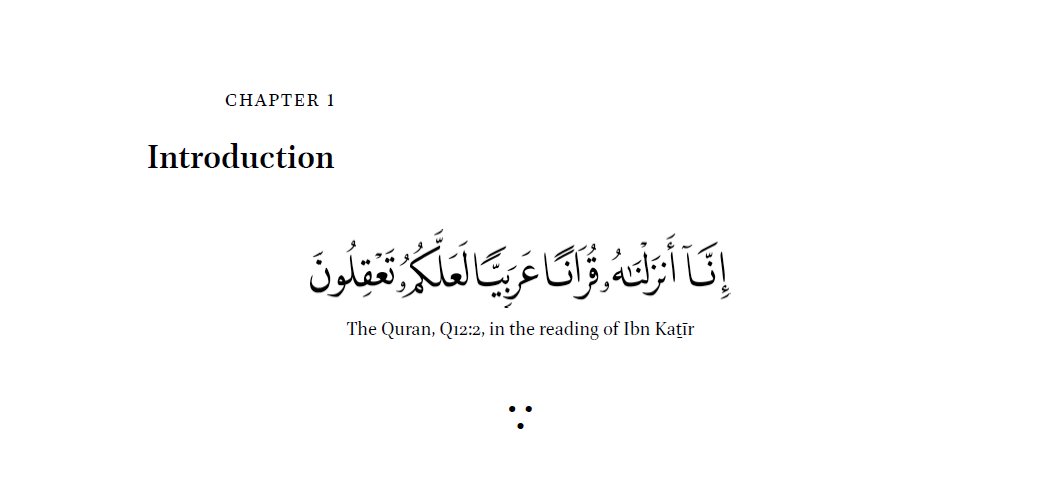

So the main question my book sets out to answer is: "What is the language of the Quran?"

There's an easy but unhelpful answer: "the language that you find in the Quran."

But what kind of language is that? Obviously Arabic. What kind of Arabic? What were its linguistic features?

There's an easy but unhelpful answer: "the language that you find in the Quran."

But what kind of language is that? Obviously Arabic. What kind of Arabic? What were its linguistic features?

As I set out to answer this question, I became more and more amazed by the fact that, somehow, this question hardly ever has gotten asked in scholarship. And the answer has typically been: "It's Classical Arabic".

And then nobody went on to define "Classical Arabic".

And then nobody went on to define "Classical Arabic".

Occasionally scholars would claim, but not defend in any way shape or form, that the language of the Quran was "identical" to the language of poetry (which was in turn sometimes identified as "Classical Arabic"). The earliest explicit reference I could find is by Schwally in 1919

Note here that Schwally first rejects the mere notion that the Quran could have been composed on the local vernacular (Hijazi or Qurashi Arabic), likewise within argument, and then calls it identical to the language of poetry -- a pan-Arabian literary koinē.

I think we can glean from the quote that even by his time this view had already made it into the "Zeitgeist". He takes it for granted, and doesn't explain it further, and none of the authors after him seem to really mount a defense for their assertion.

This would be fine, if the language of the Quran being identical to the language of poetry was so self-evident that it didn't need defense. But that strikes me as wrong. It is easy to find examples where the Quran noticeably opts for different options than the poets.

A striking example is found in the deictic system. The Quran uses: ḏālika "that (masculine), and hāḏihī "this (feminine)" and hunālika "there" consistently. Poetry uses this too, but frequently opts for ḏāka, hāḏī and hunāka.

Such forms are not even used once in the Quran.

Such forms are not even used once in the Quran.

The notion of a "poetic koine" is already problematic in itself. The suggestion that the poetry is linguistically homogenous is clearly problematic and has not been sufficiently demonstrated.

But, I show that later on "poetic koine" starts to be conflated with "classical Arabic".

But, I show that later on "poetic koine" starts to be conflated with "classical Arabic".

And "Classical Arabic" comes to be understood as the strict set of of linguistics norms that come to be associated with the standard literary language, but which, as we will see in chapter 2 were still very much being negotiated in early Islam.

As a result, I bring up a number authors who take for granted that the language of the Quran is identical to this literary standard; and make assertions about it that simply, in no way are true for the Quran. People who opine about its language, don't actually seem to check.

Thus, Hans Wehr, despite its orthography, takes for granted that Quranic Arabic (like "Classical Arabic") retained the hamzah in all places, citing biʾr, muʾmin and nāʾim -- apparently under the impression that those are not pronounced as bīr, mūmin and nāyim in the Quran.

Anyone who has ever opened up a Quran in the Maghreb would know that those examples are rather... let's say typical. Warš ʿan Nāfiʿ, the dominant reading traditions in that part of the world reads bīr and mūmin!

So is Warš suddenly not Quran? Have millions of Muslims been duped?

So is Warš suddenly not Quran? Have millions of Muslims been duped?

Of course not, rather there is a pervasive myth that because the Quran is "Classical Arabic" and it has been widely accepted as fact that "Classical Arabic" is whatever modern western textbooks like Wright or Fischer say it is, the language of the Quran must have these features.

This kind of implicit unexamined assumption that the Quran agrees with the modern norms are not just a thing of the past. See this recent claim claim that final ā written with ʾalif and yāʾ are pronounced identically in tajwīd.

Not even quite true for the dominant Ḥafṣ reading!

Not even quite true for the dominant Ḥafṣ reading!

Zwettler calls nabīʾ (نبيء) for nabiyy 'prophet' "a peculiarly Ḥijāzī pseudo-correction and a feature neither of the ʿarabiyya [= Classical Arabic] nor of the other dialects."

This, while Zwettler, proudly claims the Quran = ʿArabiyyah. Apparently Warš once again isn't Quran.

This, while Zwettler, proudly claims the Quran = ʿArabiyyah. Apparently Warš once again isn't Quran.

The meme that the Quran was Classical Arabic, and Classical Arabic is completely identical with the modern standards, has been accepted so utterly, that it appears questions about the language of the Quran have gone essentially unexamined for well over a century.

Lots of opining about the language of the Quran without actually looking at it. The last real challenge to this view was by Karl Vollers in 1906. He argued the Quran had been composed in the local vernacular and had later been "classicized" by the Arab grammarians.

Vollers was essentially shouted down by his colleagues at the time. And there is plenty of things to criticize about his book, but the core question: what is the language of the Quran, AND HOW DO WE KNOW? Has, in the frenzy to discredit Vollers, been entirely ignored.

One of the reasons why we know so little about the Quran, is partially the discomfort of scholars to take the written text seriously. Can we trust the standard text as we have it today? Is it really from the 650s as the tradition would have it? The answer to this question is yes.

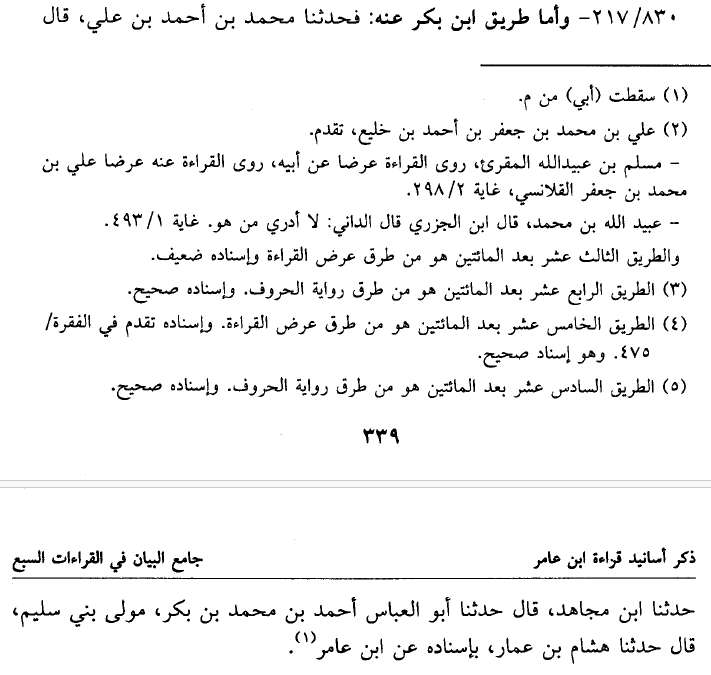

In recent years, with more access to early manuscripts, that have moreover been carbon dated, we can be confident that the standard text of the Quran was composed no more than two decades after the prophet's lifetime.

It's rasm (consonantal text) is ancient and can be studied.

It's rasm (consonantal text) is ancient and can be studied.

In the study of the language of the Hebrew bible, it has long been understood that the consonantal skeleton is ultimately the guide to the actual original language of composition, not its reading tradition. This has simply never even been entertained for the Quran.

The Quran has never been allowed to tell its own story about what its language is; instead, convoluted arguments have been developed why we should not use the Quranic text as our guide, all the while uncritically accepted Ḥafṣ and ONLY Ḥafṣ as the "true" language of the Quran

Before we can continue with our examination of the language of the Quran, we first must address the elephant in the room: "Classical Arabic/the ʿarabiyyah/the poetic koine". What is it? And how do we know? That is what chapter 2 focuses on, which we'll discuss in the next thread!

If you enjoyed this thread, and would like to support me and get exclusive access to my work-in-progress critical edition of the Quran, consider becoming a patron on patreon.com/PhDniX/!

You can also always buy me a coffee as a token of appreciation.

ko-fi.com/phdnix

You can also always buy me a coffee as a token of appreciation.

ko-fi.com/phdnix

Here's the thread summarizing chapter 2:

https://twitter.com/PhDniX/status/1495859227495174144

The thread summarizing chapter 3:

https://twitter.com/PhDniX/status/1497310468301627396

The threas summarizing chapter 4:

https://twitter.com/PhDniX/status/1498392856213573639

The thread summarizing chapter 5:

https://twitter.com/PhDniX/status/1499173480822157313

The thread summarizing chapter 6:

https://twitter.com/PhDniX/status/1500107127301492739

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh