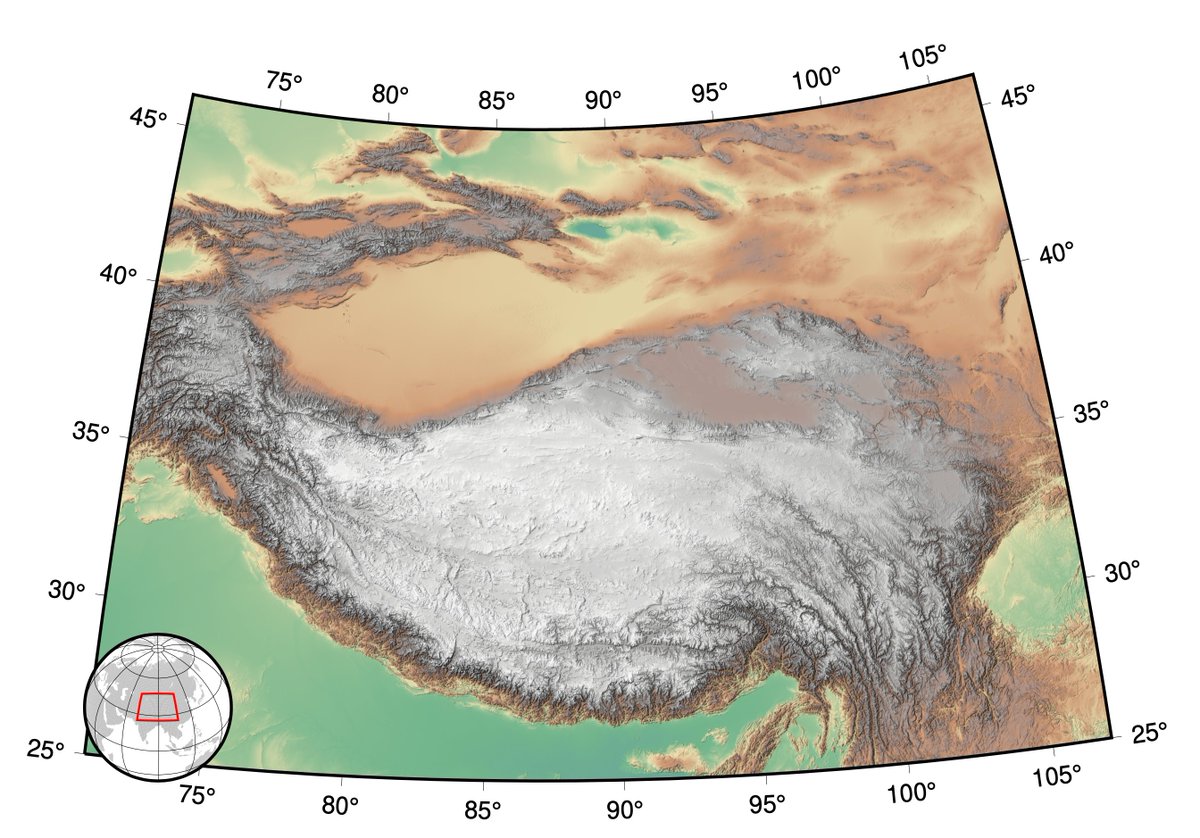

People sometimes talk about how the seafloor is one of the great unexplored mysteries - and it's true - but there's a vast region of land that also qualifies: the Tibetan Plateau. 🧵 1/

Standing at ~4.8 km above sea level (15,700 ft), the Plateau is extremely inhospitable to humans: oxygen is almost halved compared to sea level. Operating at this altitude is difficult: movement is exhausting, thinking is hard. 2/

theconversation.com/how-does-altit…

theconversation.com/how-does-altit…

For comparison: the highest peak in the continental US is Mt. Whitney, at 14,494 feet (4418 m).

That's lower than the AVERAGE elevation of the Tibetan Plateau - a region 2000 km x 1000 km! 3/

That's lower than the AVERAGE elevation of the Tibetan Plateau - a region 2000 km x 1000 km! 3/

The Tibetan Plateau covers 2.5 million square km. That's equivalent to California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, AND Texas combined.

That's 60% of the area of the EU, or 78% the area of India. 4/

That's 60% of the area of the EU, or 78% the area of India. 4/

Tibetans, who have lived at these altitudes for generations, actually have a genetic adaptation that modifies their red blood cells, allowing them to cope with low oxygen levels. (This gene matches 41,000 yr old DNA from a group of extinct humans!) 5/

bbc.com/news/science-e…

bbc.com/news/science-e…

So: the Tibetan Plateau is huge and high. But although you might usually think of mountains as rugged, the plateau is also SUPER FLAT. (The borders of the plateau stand taller - most impressively to the south: the Himalaya with Mt. Everest at 8849 m). 6/

So, WHY?

Why is the plateau so high?

Why is it so big?

Why is it so flat?

The answer lies in geology and plate tectonics. 7/

Why is the plateau so high?

Why is it so big?

Why is it so flat?

The answer lies in geology and plate tectonics. 7/

Earth's continents go through "supercontinent cycles": the continents collide, stick, and then break apart.

The last supercontinent was Pangaea. It started to break up about 225 million years ago - not long after early dinosaurs started to appear in the fossil record. 8/

The last supercontinent was Pangaea. It started to break up about 225 million years ago - not long after early dinosaurs started to appear in the fossil record. 8/

Pangaea broke into two parts, basically representing today's northern & southern continents.

But ~120 million years ago, India split off of the southern half and started to move north. 9/

xkcd.com/1449/

But ~120 million years ago, India split off of the southern half and started to move north. 9/

xkcd.com/1449/

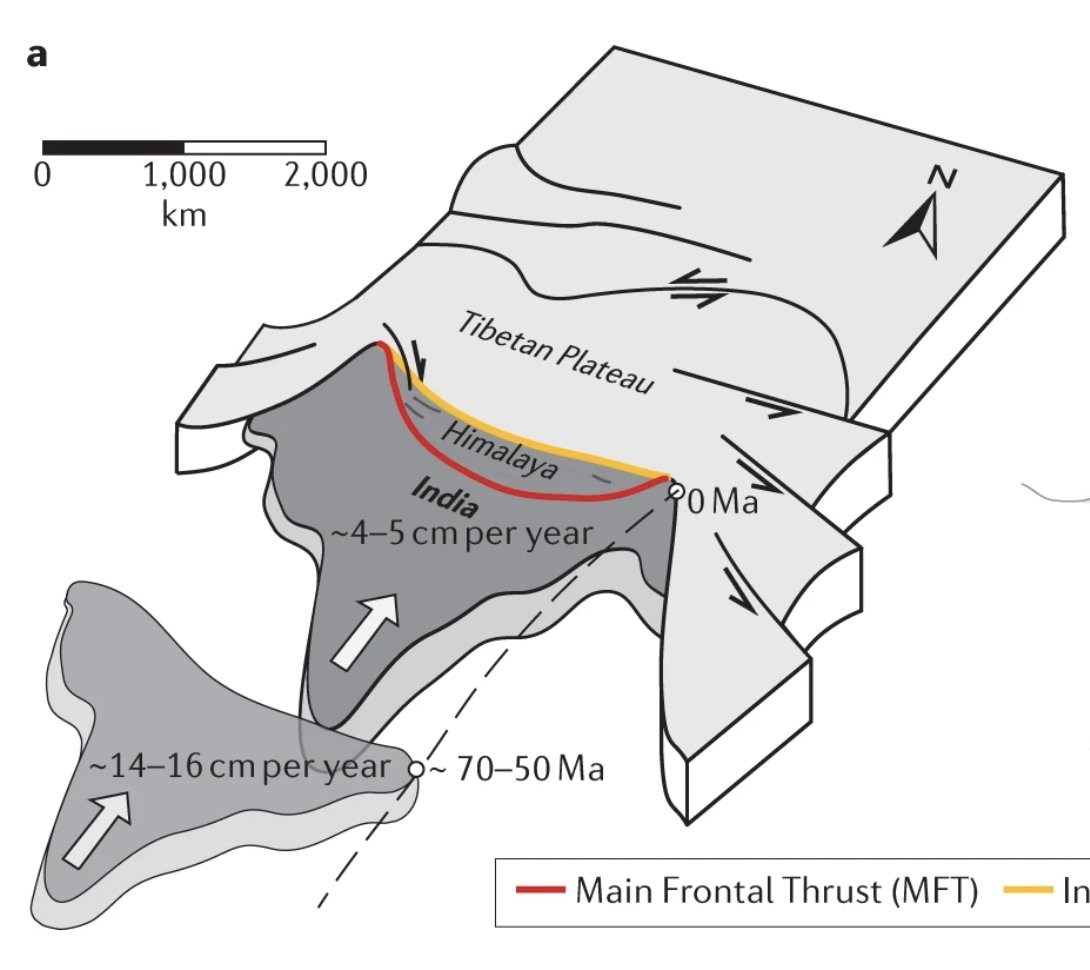

What was driving this? Like most plate movements, subduction of oceanic crust in between. Oceanic crust is made of mantle material. As it cools, it becomes denser than the mantle below. If it gets the chance, it sinks, pulling continents along behind. 10/

researchgate.net/figure/Tectoni…

researchgate.net/figure/Tectoni…

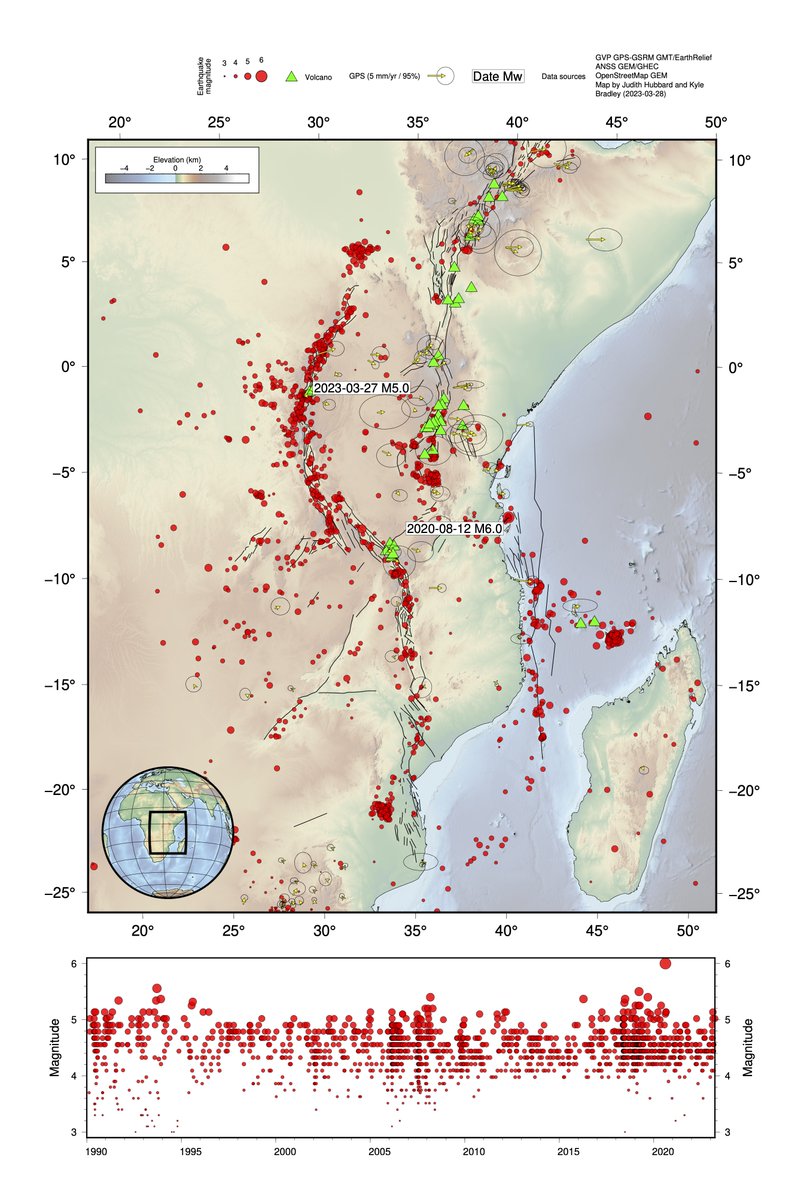

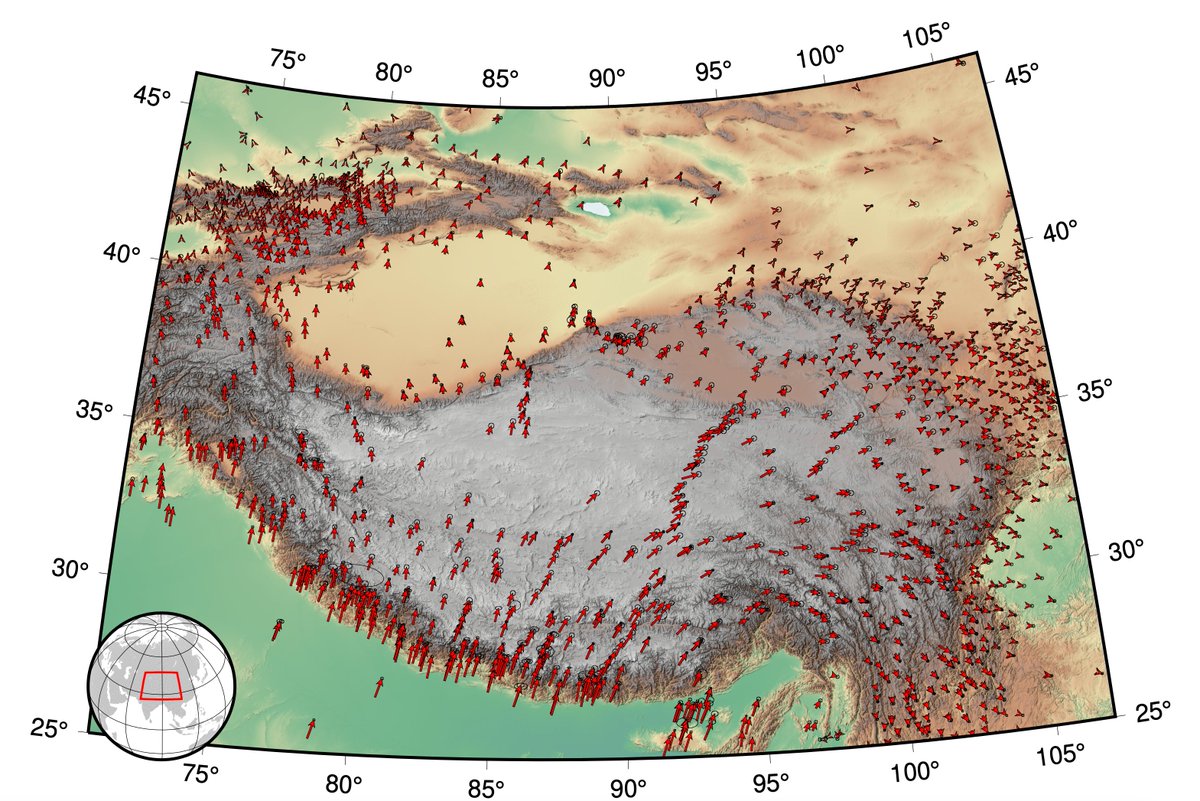

There's no ocean between India and Eurasia today, of course - because ~50 million years ago, the oceanic crust finally subducted away, and the two blocks collided. The plateau has been growing ever since.

Here's how the plates are moving today. 11/

Here's how the plates are moving today. 11/

More than 1,400 km of shortening has occurred across the Plateau. All that material had to go somewhere! A lot of it went into thickening the crust: it doubled to ~60-70 km thick. A lot got squeezed to the sides - that's why the Plateau is so wide. 12/

doi.org/10.1038/s43017…

doi.org/10.1038/s43017…

That extra-thick crust supports the high elevations of the Plateau ("isostasy"). Because continental crust is less dense than the mantle, these low-density roots balance the extra mass above. (Just like icebergs!) 13/

doi.org/10.1038/417911a

doi.org/10.1038/417911a

Why is the Plateau flat? This may partly be because many rivers drain inward, so mountains erode and fill nearby valleys. It's also possible that the deep crust moves and deforms in response to gravitational forces, "levelling" the surface. 14/

But the question of how exactly the crust got thick remains debated. One plate slid under another? Giant thrust faults progressively active from south to north? Flow of deep material?

The plateau makes answering these questions hard, because... 15/

DOI: 10.1126/science.105978

The plateau makes answering these questions hard, because... 15/

DOI: 10.1126/science.105978

...it's so hard to work there! Understanding the subsurface is ALWAYS hard but geoscientists have ways to image it. Those methods involve deploying instruments - to listen to earthquakes, listen to echoes of our own signals, record magnetic field and gravity variations. 16/

We've done some of this in the Plateau, but it's HARD. High altitude, only occasional roads, limited facilities.

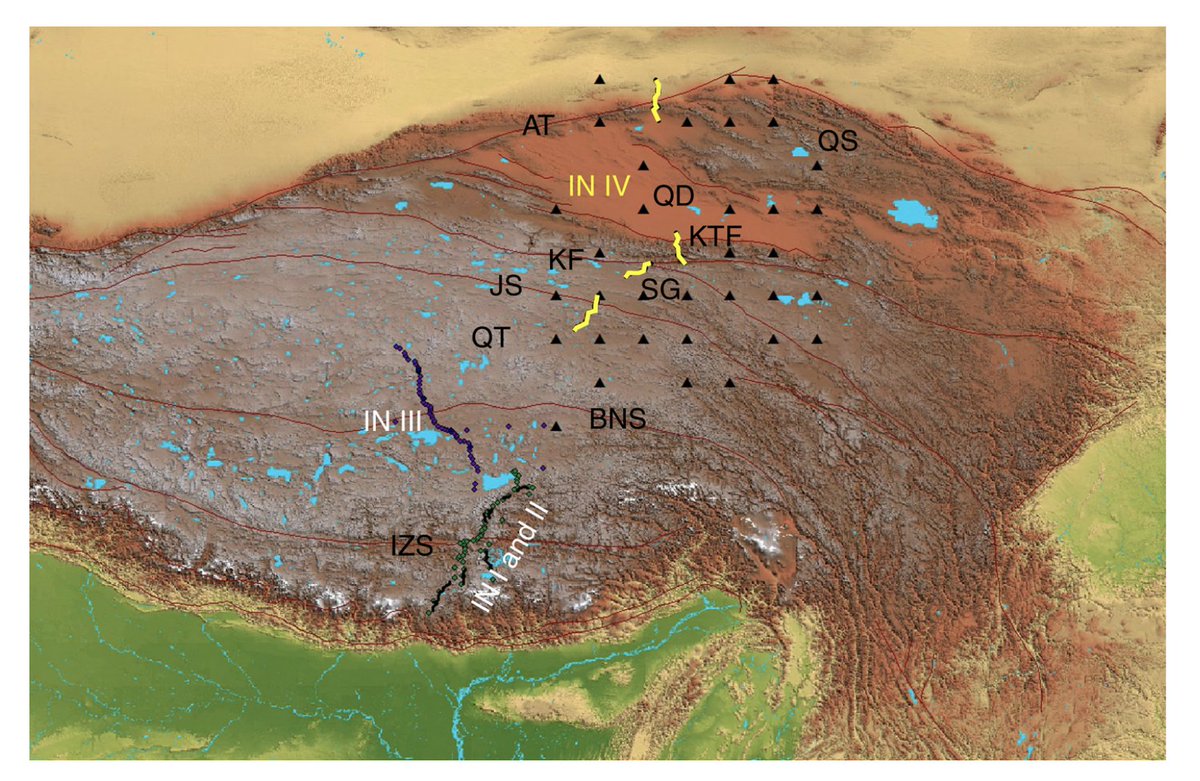

For example, here are the locations of the INDEPTH experiments (started 1992). Sparse, largely following roads. 17/

geo.cornell.edu/geology/brown/…

For example, here are the locations of the INDEPTH experiments (started 1992). Sparse, largely following roads. 17/

geo.cornell.edu/geology/brown/…

Of course, even perfect images of the subsurface today wouldn't tell us how the Plateau grew over 50 million years. We have to piece that together from clues - leaf fossils, fragments of volcanic rock, bits of limestone. 18/

doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nw…

doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nw…

But you need a LOT of clues to build a story that spans 2.5 million square km & 50 million yrs.

And each clue requires traveling to high altitude, mapping the rocks to understand the context, and careful lab work to date the samples. 19/

Photo from: lh5.googleusercontent.com/p/AF1QipOAAIC7…

And each clue requires traveling to high altitude, mapping the rocks to understand the context, and careful lab work to date the samples. 19/

Photo from: lh5.googleusercontent.com/p/AF1QipOAAIC7…

Incongruously, despite its inaccessibility, the Plateau has been imaged in detail by satellites - little atmospheric distortion to get in the way! These reveal a stark but beautiful landscape, dotted with icy lakes. 20/

#GoogleEarth

#GoogleEarth

The occasional village is terraced into the sides of valleys, proof that the region CAN support life, at least in some places. 21/

#GoogleEarth

#GoogleEarth

Folded and faulted rocks hint at the millions of years of tectonic convergence, but most of that record lies beneath the surface. 22/

#GoogleEarth

#GoogleEarth

And in some regions, sands eroded from the growing Plateau drift in dunes across the rocks, obscuring even those geological hints. 23/23

#GoogleEarth

#GoogleEarth

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh