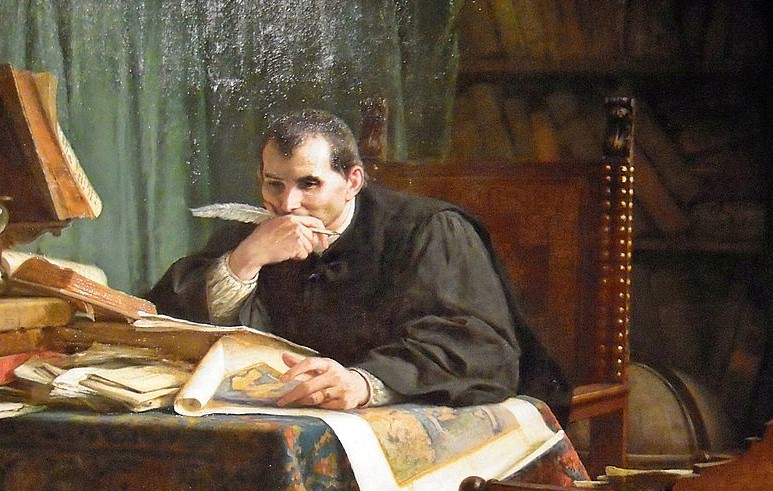

Machiavelli is definitely an interesting character, but his opinions are accepted too uncritically in the modern age and he is in this regard somewhat overrated.

Machiavelli was definitely completely wrong with his negative opinions about the mercenaries and I'll explain why.

Machiavelli was definitely completely wrong with his negative opinions about the mercenaries and I'll explain why.

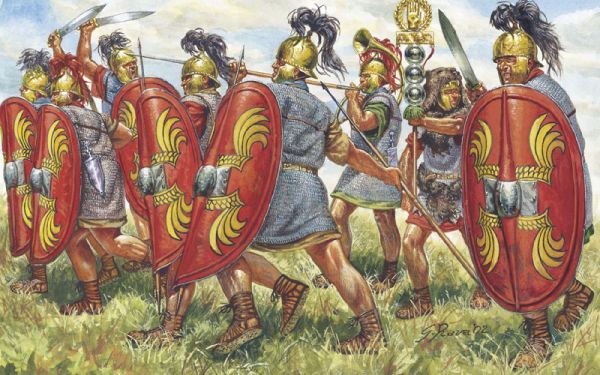

Machiavelli hated the mercenaries and wanted to recruit some sort of citizen army for which he gave historic examples of Rome and Sparta, claiming that such army would be more loyal and just overall superior to mercenary armies of the time.

In his opinion mercenaries were not just disloyal but he even described them as cowardly, undisciplined, useless.

He was wrong on that alone as anyone who studied the legendary medieval mercenaries like Varangians or the Swiss can confirm.

But he was wrong on more than that.

He was wrong on that alone as anyone who studied the legendary medieval mercenaries like Varangians or the Swiss can confirm.

But he was wrong on more than that.

Machiavelli's idea was that by training citizens he could have them reach the level of mercenaries and then surpass it through some patriotic pathos and loyalty.

This opinion was widely popularized by modern nationalism which loathed mercenaries for the same reason.

This opinion was widely popularized by modern nationalism which loathed mercenaries for the same reason.

Now you can argue that what Machiavelli said could be true for modern times, but the reality of the time of which Machiavelli wrote was vastly different. His opinion distorted the image of renaissance and medieval mercenaries to some extent, and this has to be refuted.

Machiavelli criticized the French King for employing Swiss mercenaries and that by contributing to their reputation he demoralized his own troops by making them think they were inferior to Swiss.

He thought it would be better had the French focused solely on training their own.

He thought it would be better had the French focused solely on training their own.

But the fact was that the Swiss were superior. Now obviously the French had their own elite troops in French knights, but their infantry was lacking. However the French historically did try to to train their own infantry, but failed badly, something Machiavelli doesn't cover.

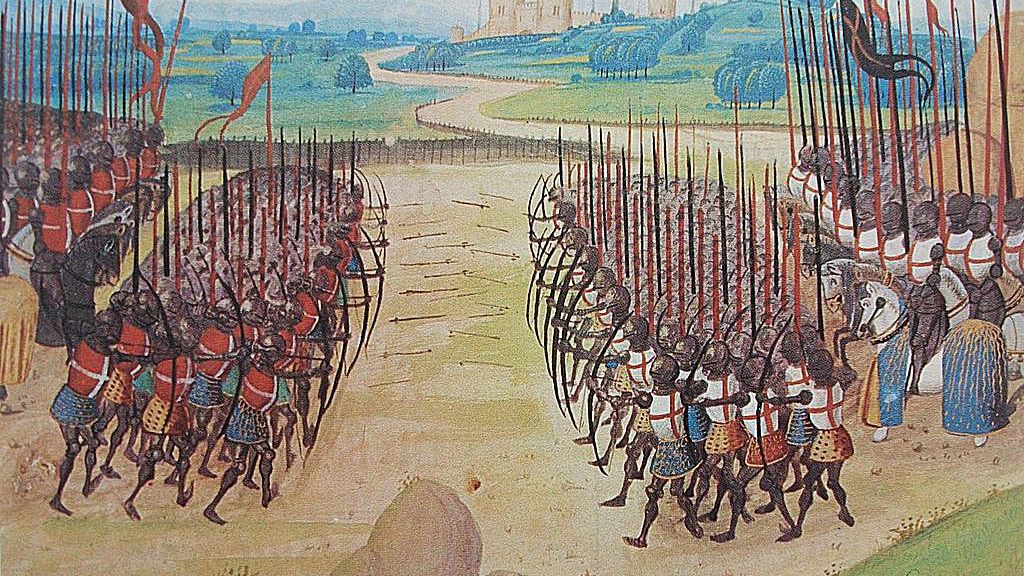

After seeing the effectiveness of English longbowmen tactics, the French tried something similar on their own by training the so-called Franc-archers (free archers) from their own citizens. But these Franc-archers fared very poorly and were disbanded in 1480.

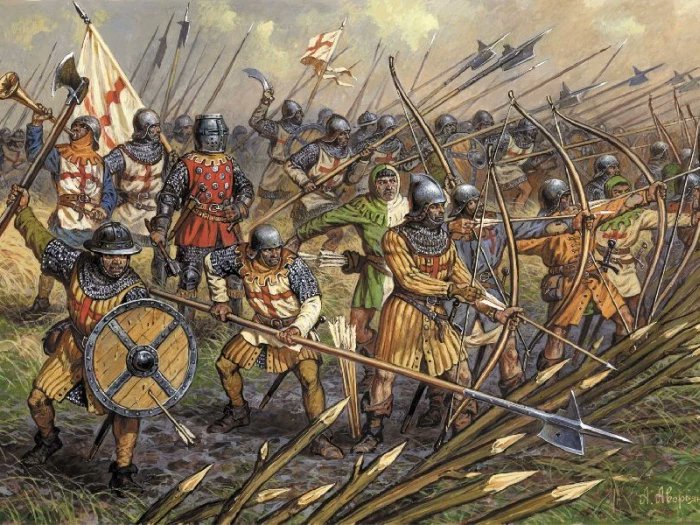

Medieval warfare required a lot of skill and warrior spirit and it was simply not possible to just train a group of peasants or burghers and expect them to match the elite mercenaries and knights over night. The French learned this and employed the Swiss mercenaries.

This lesson was overlooked by Machiavelli and is still overlooked today.

This is largely due to myth of a medieval "military revolution" which asserts that knights were losing their military superiority due to advance of certain weapons and tactics that nullified heavy cavalry.

This is largely due to myth of a medieval "military revolution" which asserts that knights were losing their military superiority due to advance of certain weapons and tactics that nullified heavy cavalry.

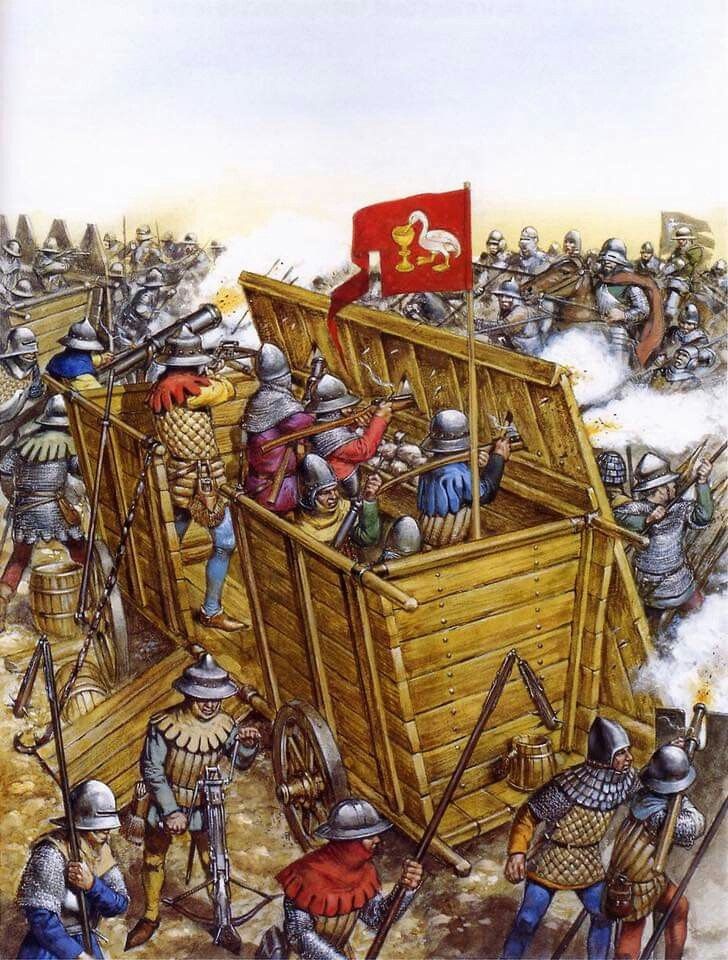

While there were certain types of infantry tactics that could be successful against heavy cavalry like longbowmen (+ dismounted knights), Hussite war wagons and pike squares, these tactics relied on skills and ethos of the men who executed them. And these men were very rare.

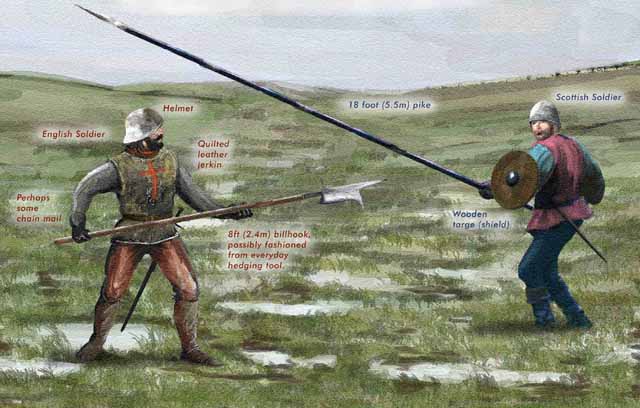

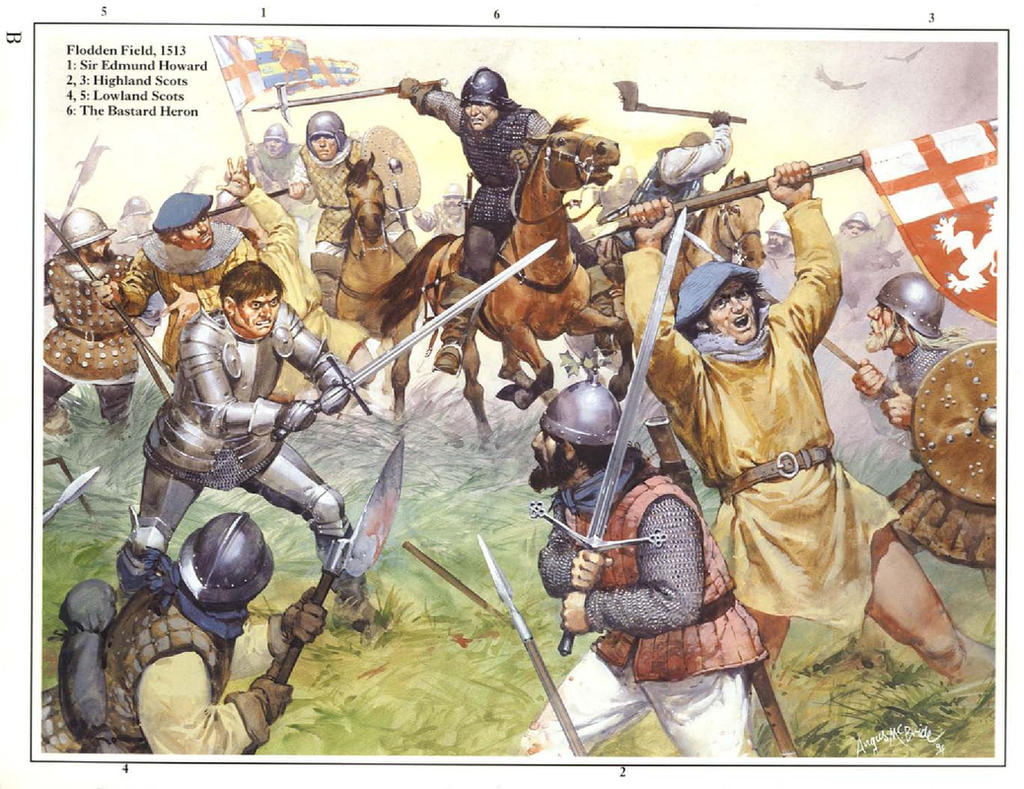

You could not just give longbows, pikes or other types of otherwise great weapons to regular people and expect them to be good at it, even after training. This was proved many times, for example at Flodden in 1513 where Scots were given pikes but couldn't use them effectively.

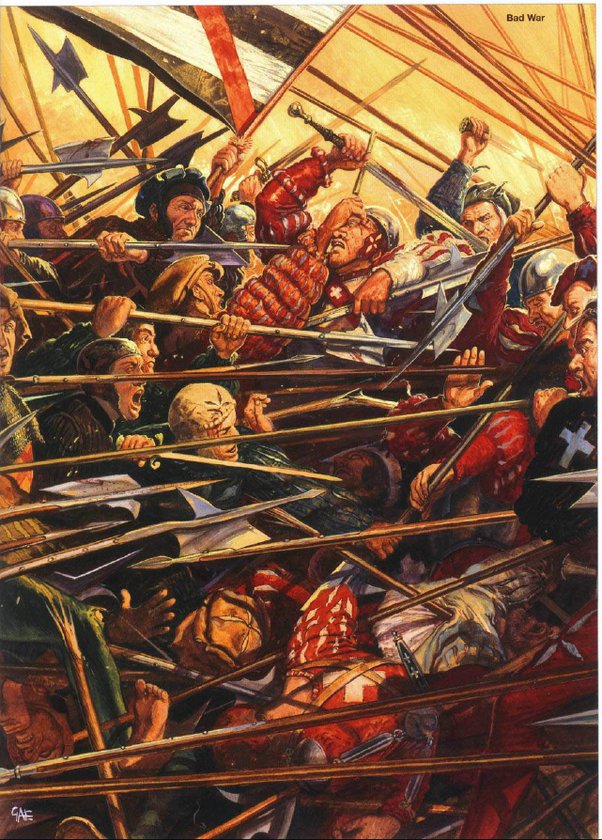

There's a reason why only three types of pikemen distinguished themselves above others historically, the Swiss, the Landsknechts and the Tercios. Even though everyone used pikes, elite pikemen units were rare. It was just a brutal type of warfare and not everyone was up for it.

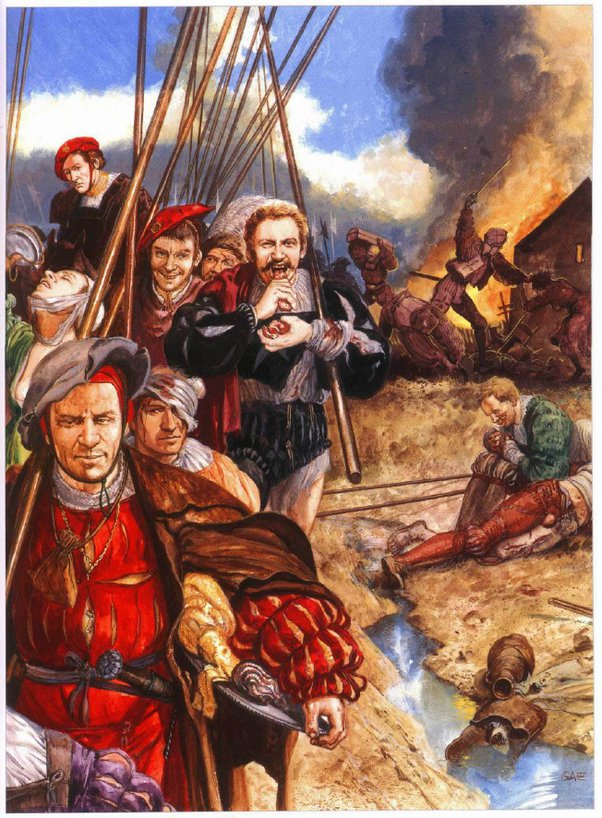

And we see the effectiveness of the Swiss compared to local French pikemen even much later. At the Battle of Dreux in 1562 during French wars of religion, the Swiss mercenaries were the only pikemen infantry who did not fall apart and were crucial for the Catholic victory.

This is despite the local pikemen infantry on both sides being motivated by religious fanaticism, but this helped little when they engaged in serious brutal warfare for which the Swiss were better suited due to their warrior culture. The others fell apart while the Swiss held on.

It's also wrong to assume the likes of Swiss mercenaries were unmotivated or disloyal because they fought for money. They also fought for their own reputation as mercenaries and warriors. Honor culture was a big part of being a medieval or renaissance mercenary.

It's ironic that Machiavelli actually lists the Swiss Confederacy as one of his preferred examples of a state that can be defended by its citizens, when this Swiss state was defended by the fierce reputation of its mercenaries for which no one dared to attack it, for good reason.

The other two examples he gives of Rome and Sparta were simply in a different era. The military prowess of Roman and Spartan armies took time to develop. It was a vastly different case than Machiavelli suggesting to train troops that could face the elite of his time over night.

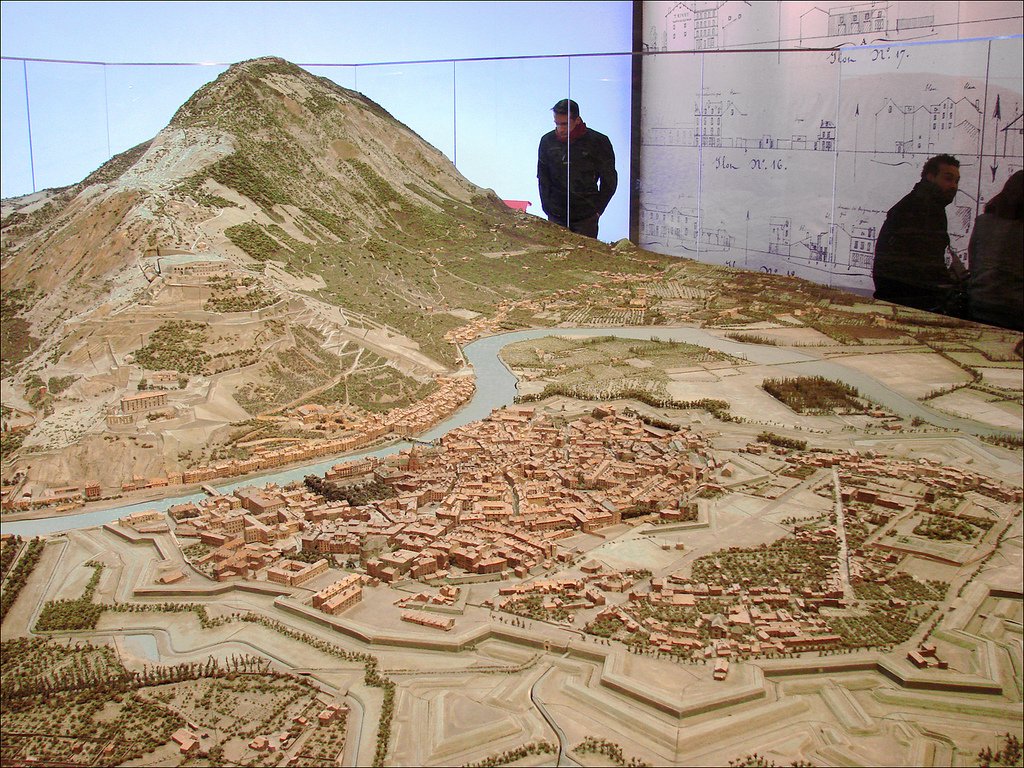

Why did Machiavelli not see that? Well coming from Florence, he was essentially engaging in what today would be called "cope". The importance of this historically great city-republic was fading in the face of mighty and imposing mercenary armies of France and Holy Roman Empire.

Italian city-states could not afford to upkeep large mercenary armies, especially not the costly mercenaries like the Swiss. This made them open for invasion by these large emerging centralized superpowers like France who could assemble big armies and just devastate them at will.

Machiavelli basically tried to convince himself and his state that by training a local force out of citizens and peasantry they would be able to sustain the pressure from strong foreign empires and pursue independent politics, and forging a superior army this way.

A lot of motivation for Machiavelli's negative views of mercenaries was also political. In republic of Florence he had trained citizen militia until the Medici took over with mercenary troops in 1512, abolished the republic and banished Machiavelli as a suspect republican.

This was also the end of Machiavelli's political life. Nevertheless he tried to win favors with the new Medici establishment. In this context, playing up the success of his idea of a citizen militia was one ways of trying to show his capabilities and a vision for Florence.

Ultimately nothing came out of that and the mercenary armies continued to dominate and ravaged and pillaged Italy as much as they wanted, and the only effective Italian troops were mercenary condottieri themselves like the Black Bands.

Interestingly, Machiavelli died just a month after the famous Sack of Rome in 1527 where the Swiss mercenaries performed a heroic last stand to defend the Pope, showcasing their loyalty and value, immortalizing themselves in history, proving Machiavelli wrong.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh