The single most undervalued fact of linear algebra: matrices are graphs, and graphs are matrices.

Encoding matrices as graphs is a cheat code, making complex behavior simple to study.

Let me show you how!

Encoding matrices as graphs is a cheat code, making complex behavior simple to study.

Let me show you how!

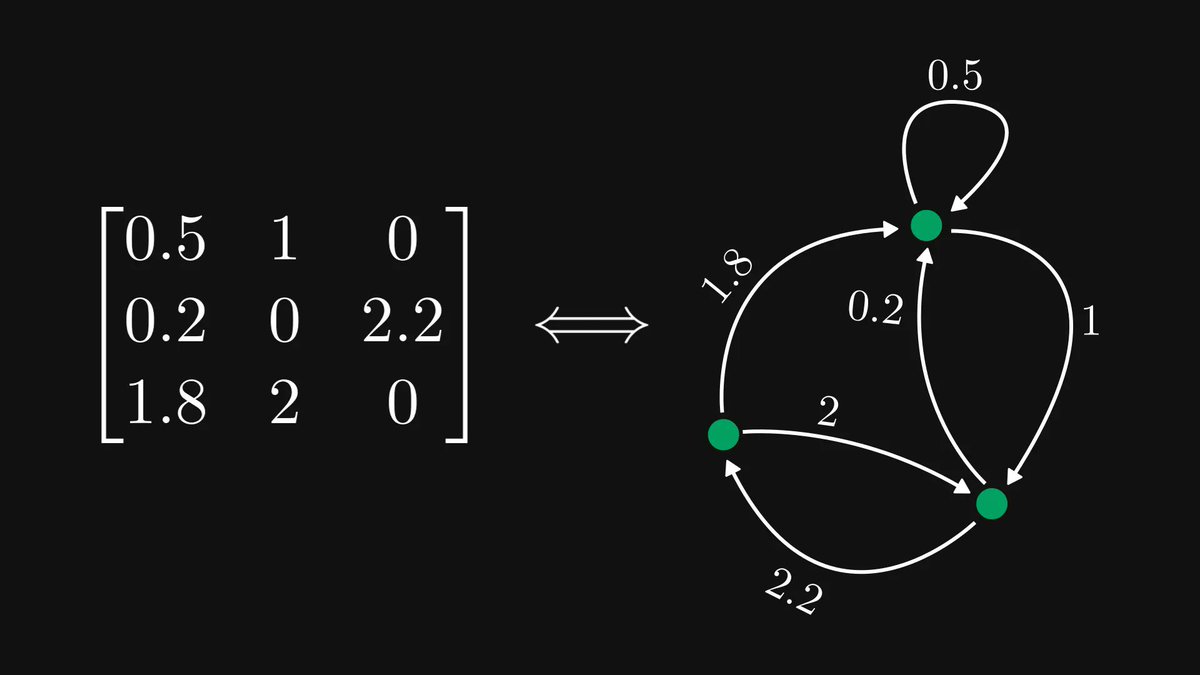

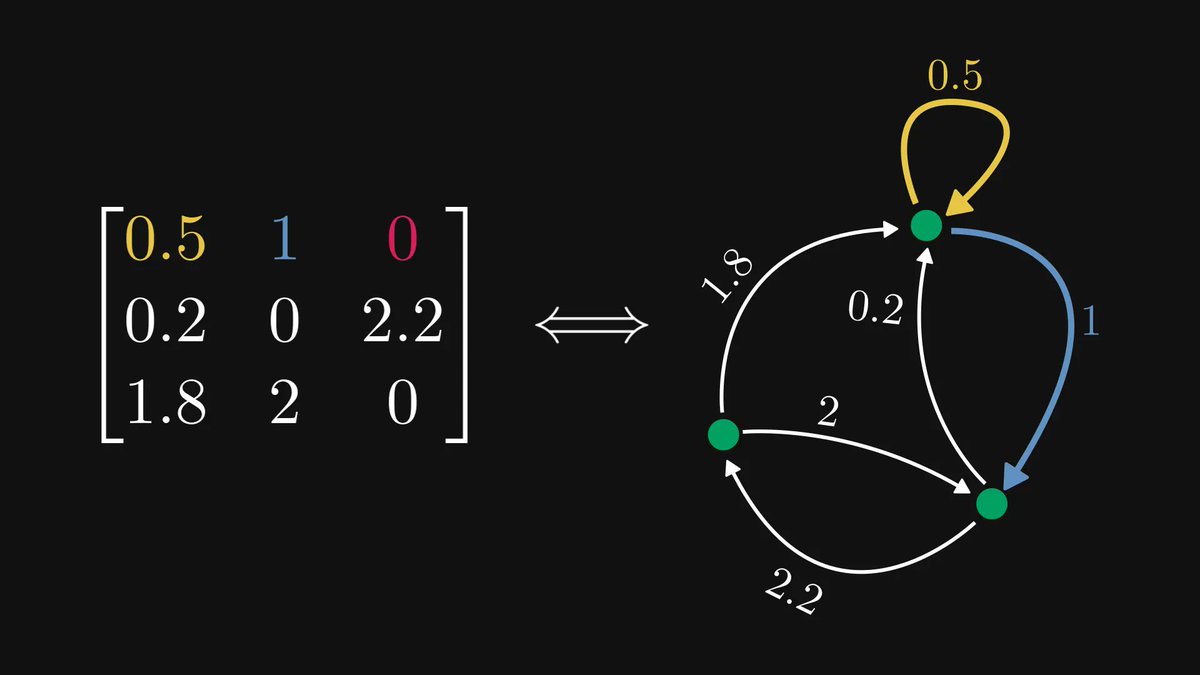

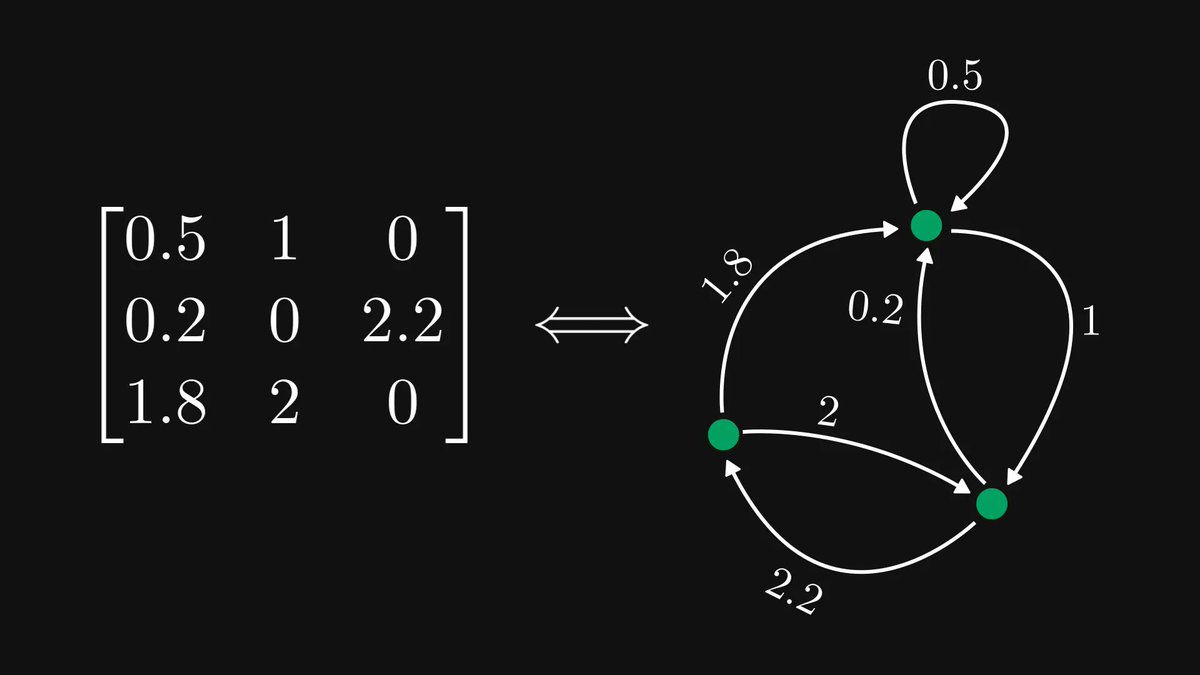

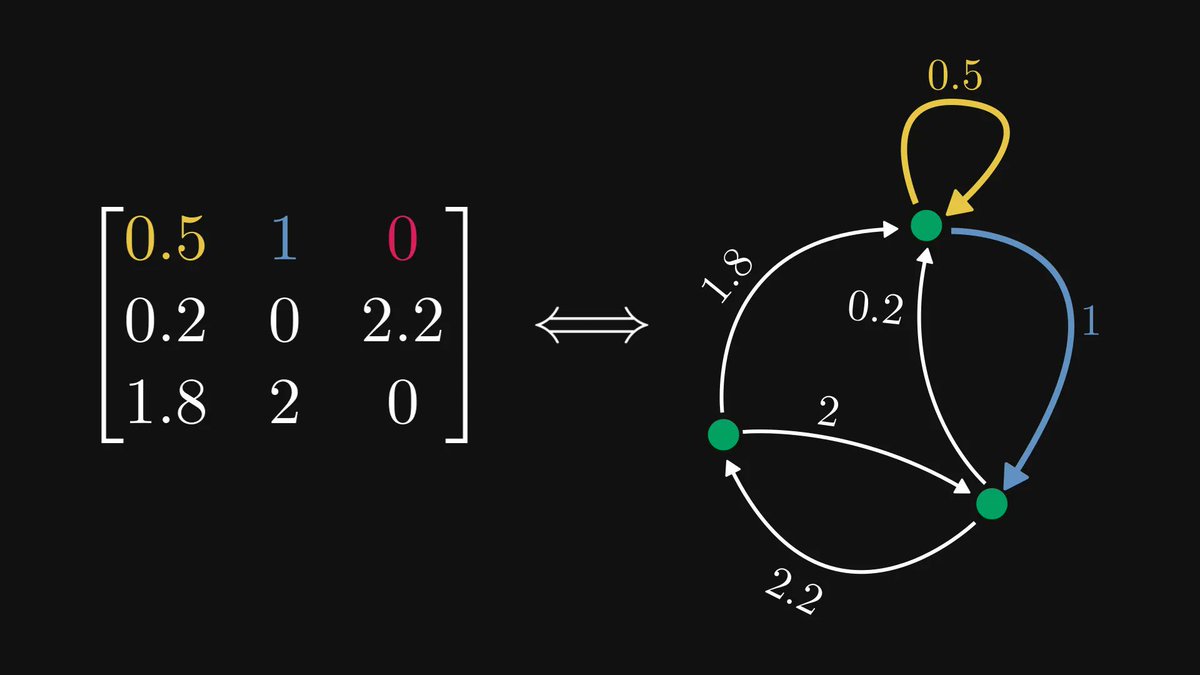

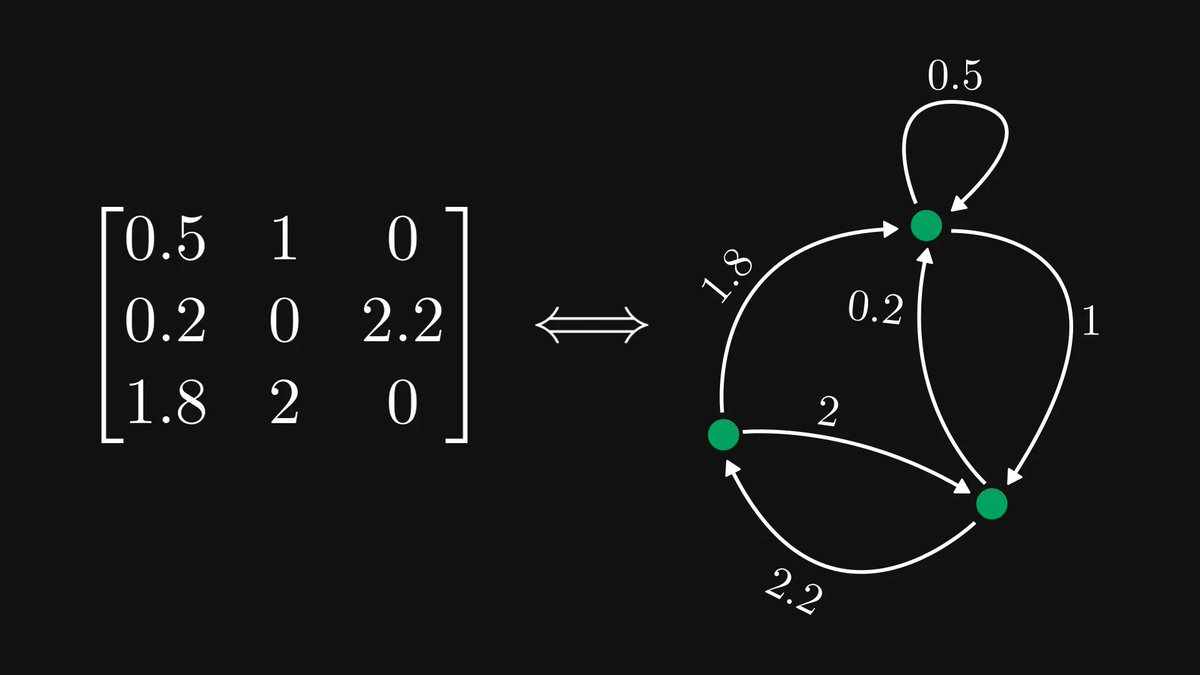

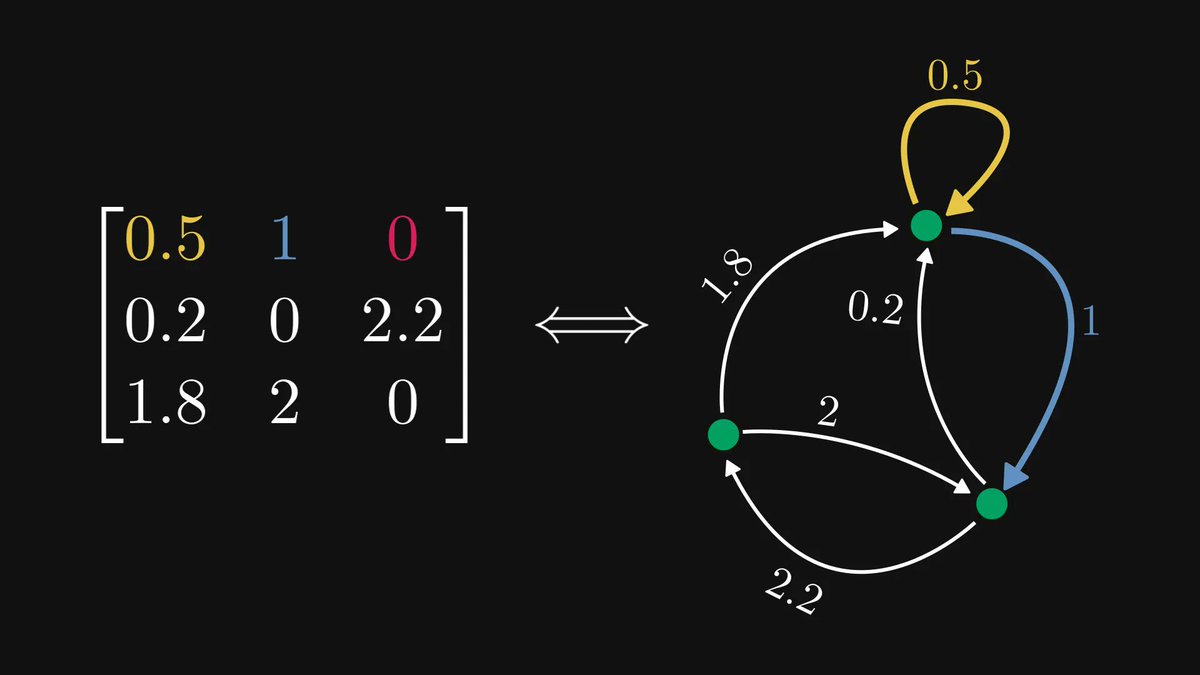

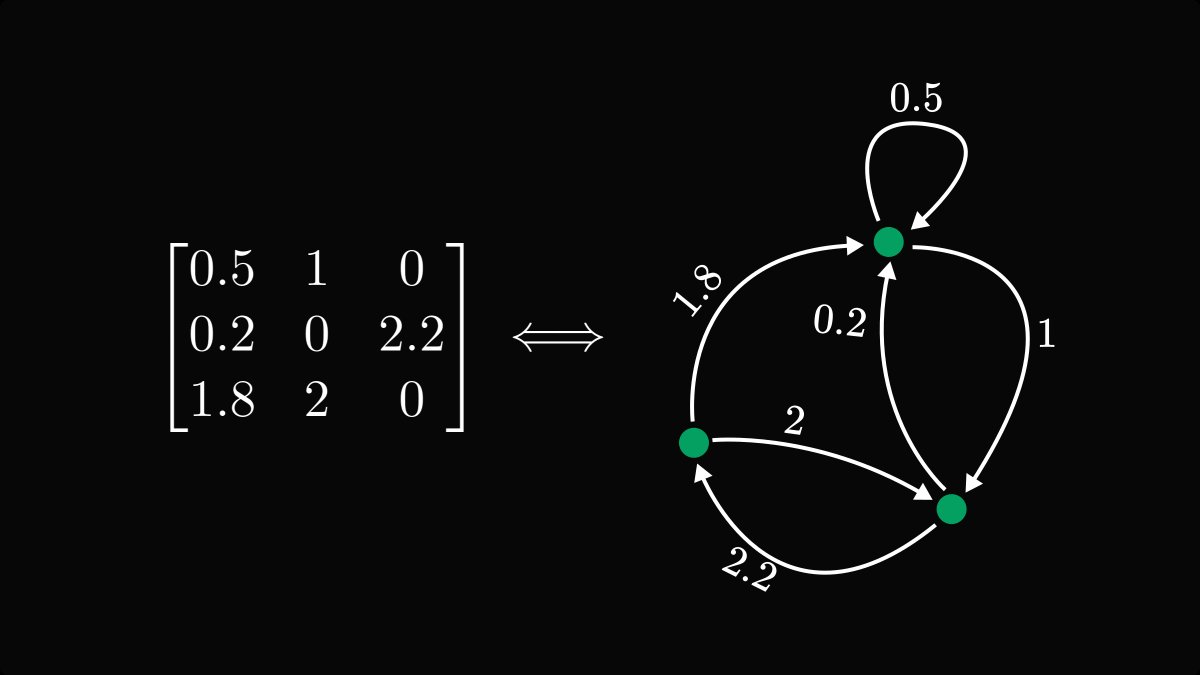

If you looked at the example above, you probably figured out the rule.

Each row is a node, and each element represents a directed and weighted edge.

The element in the 𝑖-th row and 𝑗-th column corresponds to an edge going from 𝑖 to 𝑗.

Each row is a node, and each element represents a directed and weighted edge.

The element in the 𝑖-th row and 𝑗-th column corresponds to an edge going from 𝑖 to 𝑗.

Why is the directed graph representation beneficial for us?

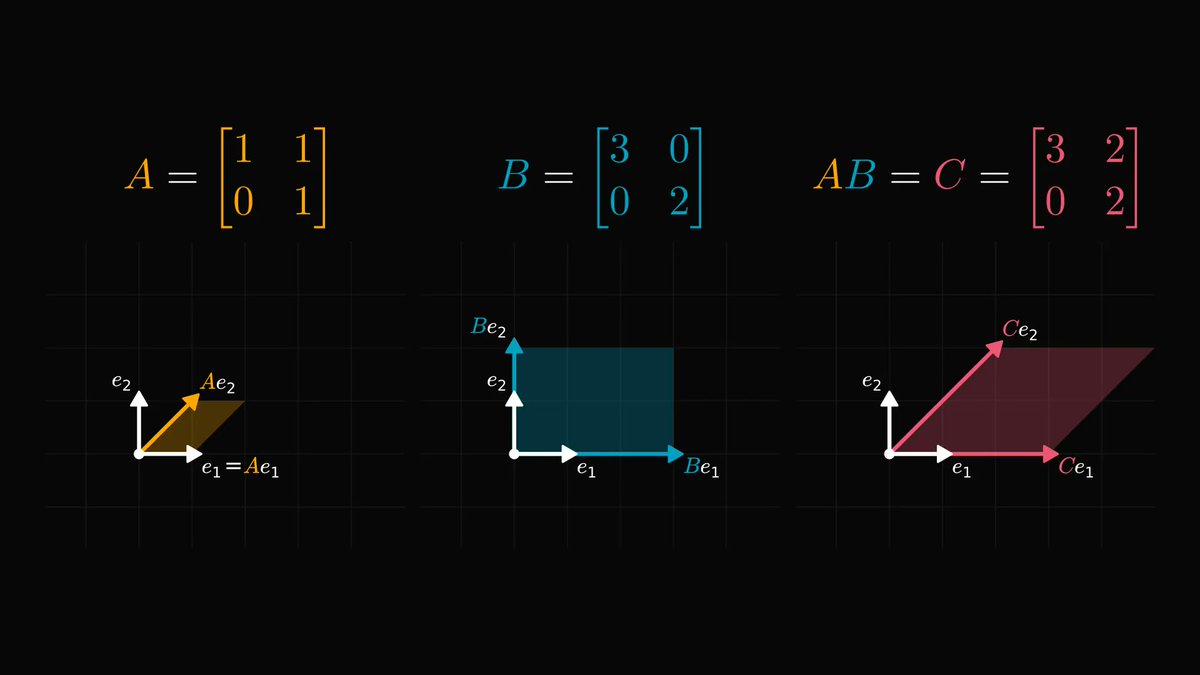

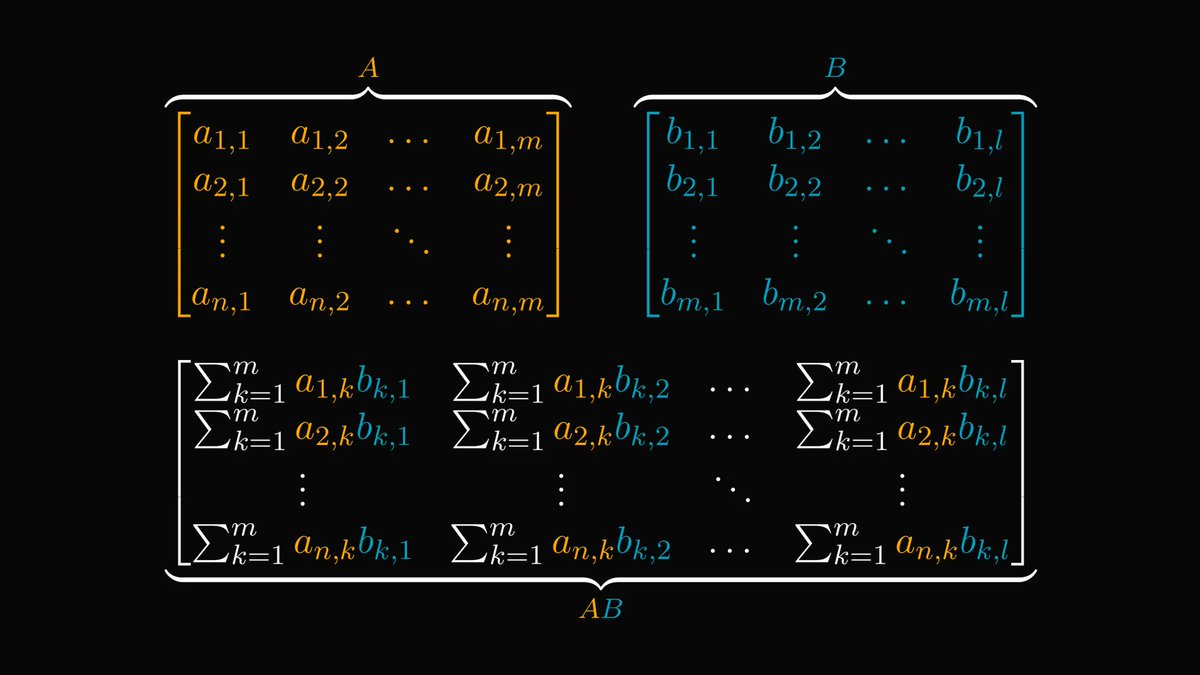

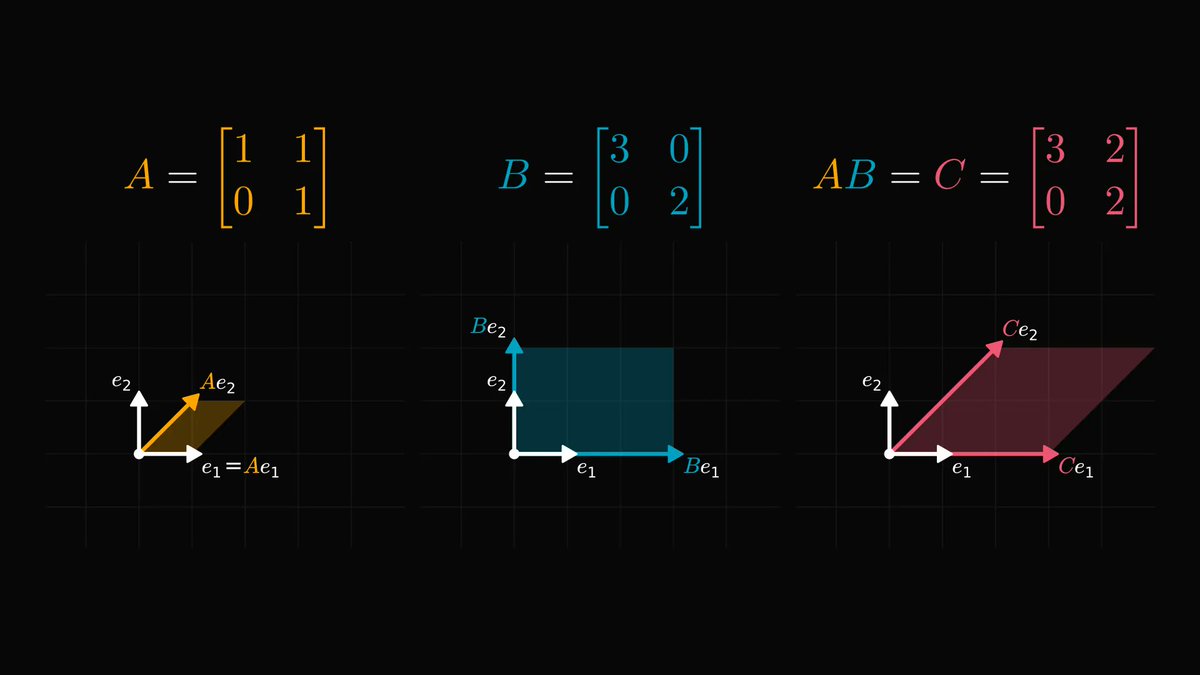

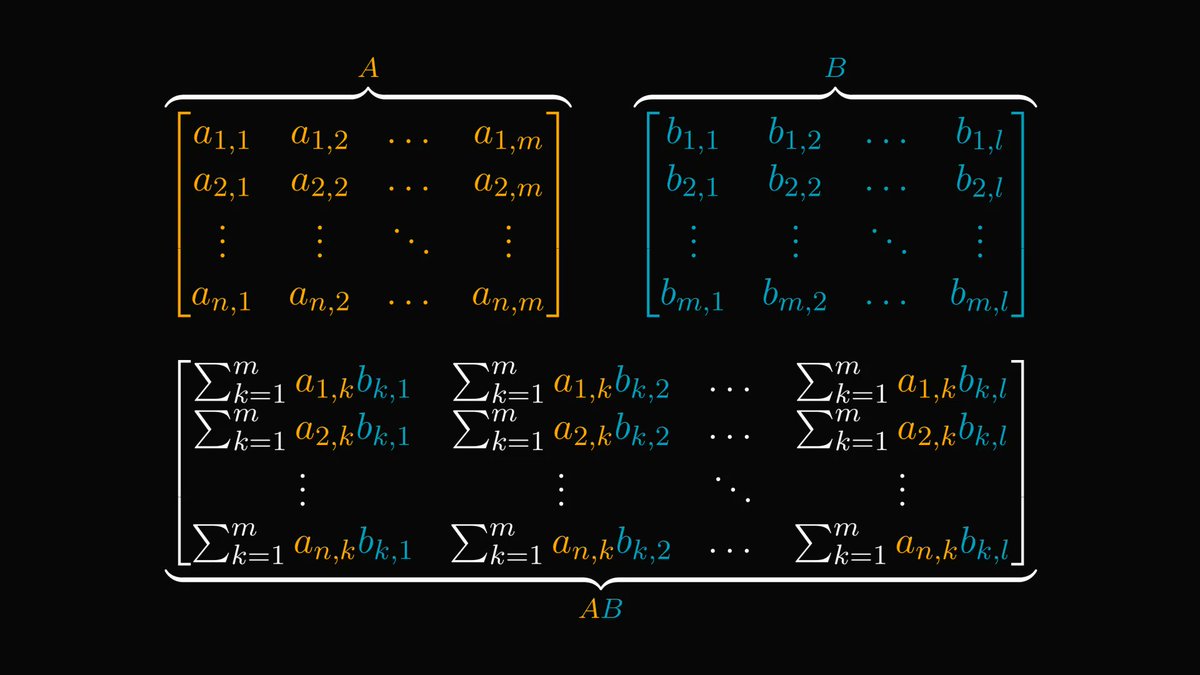

For one, the powers of the matrix correspond to walks in the graph.

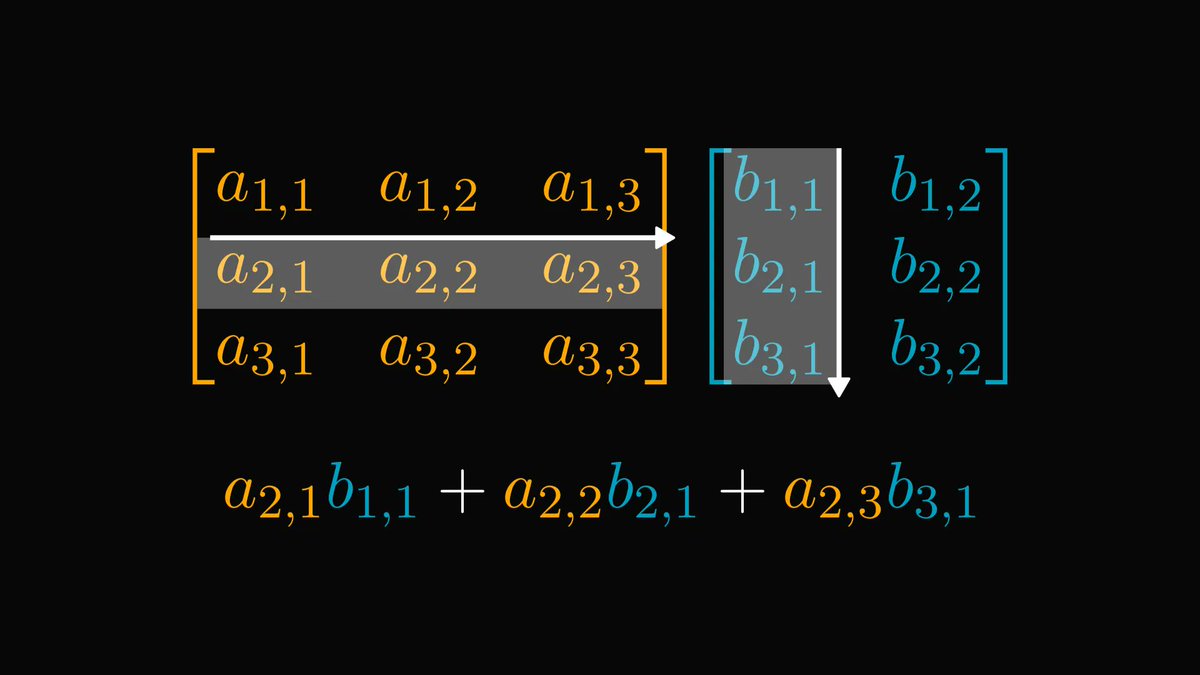

Take a look at the elements of the square matrix. All possible 2-step walks are accounted for in the sum defining the elements of A².

For one, the powers of the matrix correspond to walks in the graph.

Take a look at the elements of the square matrix. All possible 2-step walks are accounted for in the sum defining the elements of A².

If the directed graph represents the states of a Markov chain, the square of its transition probability matrix essentially shows the probability of the chain having some state after two steps.

There is much more to this connection.

For instance, it gives us a deep insight into the structure of nonnegative matrices.

To see what graphs show about matrices, let's talk about the concept of strongly connected components.

For instance, it gives us a deep insight into the structure of nonnegative matrices.

To see what graphs show about matrices, let's talk about the concept of strongly connected components.

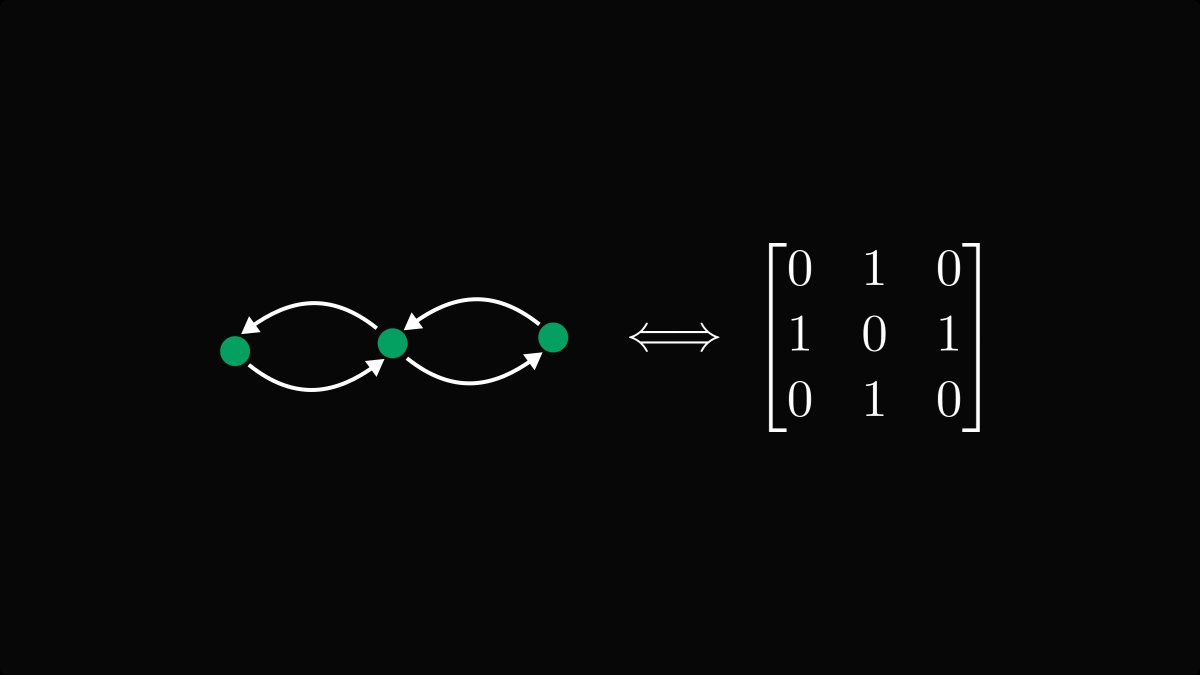

A directed graph is strongly connected if every node can be reached from every other node.

Below, you can see two examples where this holds and doesn't hold.

Below, you can see two examples where this holds and doesn't hold.

Matrices that correspond to strongly connected graphs are called irreducible. All other nonnegative matrices are called reducible. Soon, we'll see why.

(For simplicity, I assumed each edge to have unit weight, but each weight can be an arbitrary nonnegative number.)

(For simplicity, I assumed each edge to have unit weight, but each weight can be an arbitrary nonnegative number.)

Back to the general case!

Even though not all directed graphs are strongly connected, we can partition the nodes into strongly connected components.

Even though not all directed graphs are strongly connected, we can partition the nodes into strongly connected components.

Let's label the nodes of this graph and construct the corresponding matrix!

(For simplicity, assume that all edges have unit weight.)

Do you notice a pattern?

(For simplicity, assume that all edges have unit weight.)

Do you notice a pattern?

The corresponding matrix of our graph can be reduced to a simpler form.

Its diagonal comprises blocks whose graphs are strongly connected. (That is, the blocks are irreducible.) Furthermore, the block below the diagonal is zero.

Its diagonal comprises blocks whose graphs are strongly connected. (That is, the blocks are irreducible.) Furthermore, the block below the diagonal is zero.

Let's reverse the question: can we transform an arbitrary nonnegative matrix into the Frobenius normal form?

Yes, and with the help of directed graphs, this is much easier to show than purely using algebra.

Yes, and with the help of directed graphs, this is much easier to show than purely using algebra.

We have already seen the proof:

1. construct the corresponding directed graph,

2. find its strongly connected components,

3. and renumber its nodes such that the components' nodes form blocks among the integers.

1. construct the corresponding directed graph,

2. find its strongly connected components,

3. and renumber its nodes such that the components' nodes form blocks among the integers.

Without going into the details, renumbering the nodes is equivalent to reordering the rows and the columns of our original matrix, resulting in the Frobenius normal form.

This is just the tip of the iceberg. For example, with the help of matrices, we can define the eigenvalues of graphs!

Utilizing the relation between matrices and graphs has been extremely profitable for both graph theory and linear algebra.

Utilizing the relation between matrices and graphs has been extremely profitable for both graph theory and linear algebra.

If you have enjoyed this thread, share it with your friends and follow me!

I regularly post deep-dive explanations about seemingly complex concepts from mathematics and machine learning.

Understanding math will make you a better engineer, and I want to show you how.

I regularly post deep-dive explanations about seemingly complex concepts from mathematics and machine learning.

Understanding math will make you a better engineer, and I want to show you how.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh