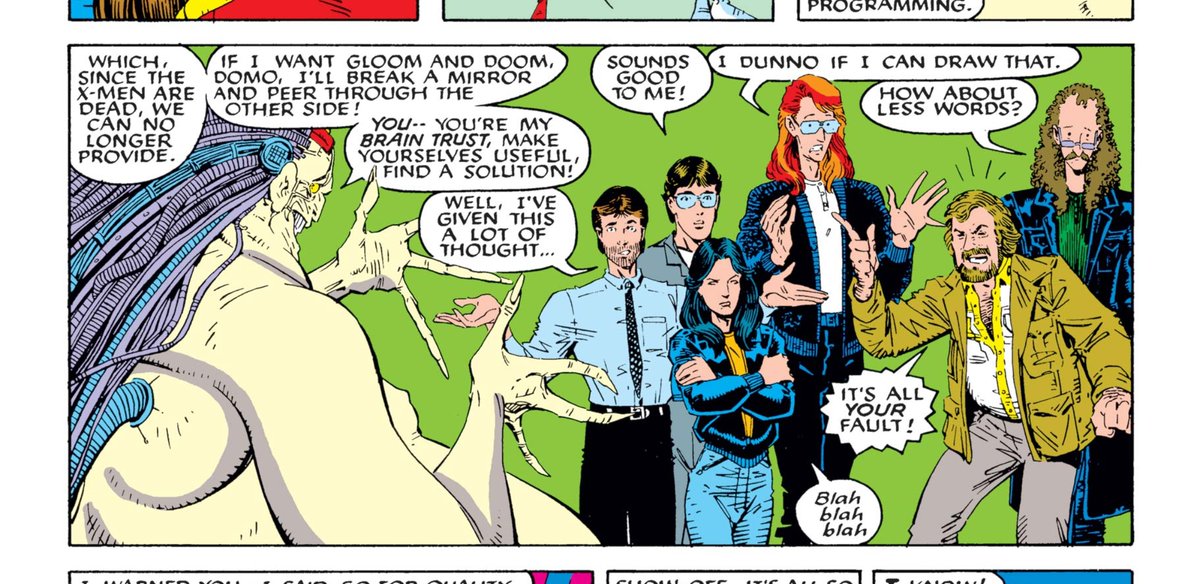

In a selected chapter for “Comics Studies: A Guidebook,” covering the very broad subject of “Superheroes,” scholar Marc Singer provides an account for the secret of Claremont’s success as writer of X-Men comics: representational metaphor. #xmen 1/6

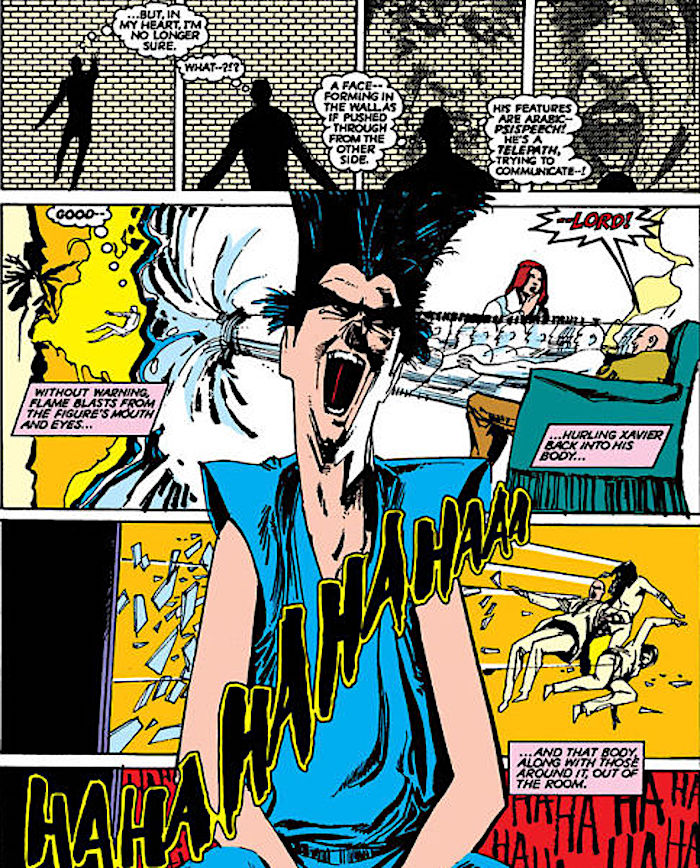

“The X-Men were depicted as objects of fear, prejudice, and oppression, leading readers to interpret them as free-floating metaphors for African American, gays, Jews, and other marginalized groups – not to mention adolescents, particularly those outcasts who read comic books” 2/6

“Turning his mutant heroes into a malleable allegory, Claremont created a powerful vehicle for reader identification by conflating a conditional social ostracism with systematic and institutional oppression.” 3/6

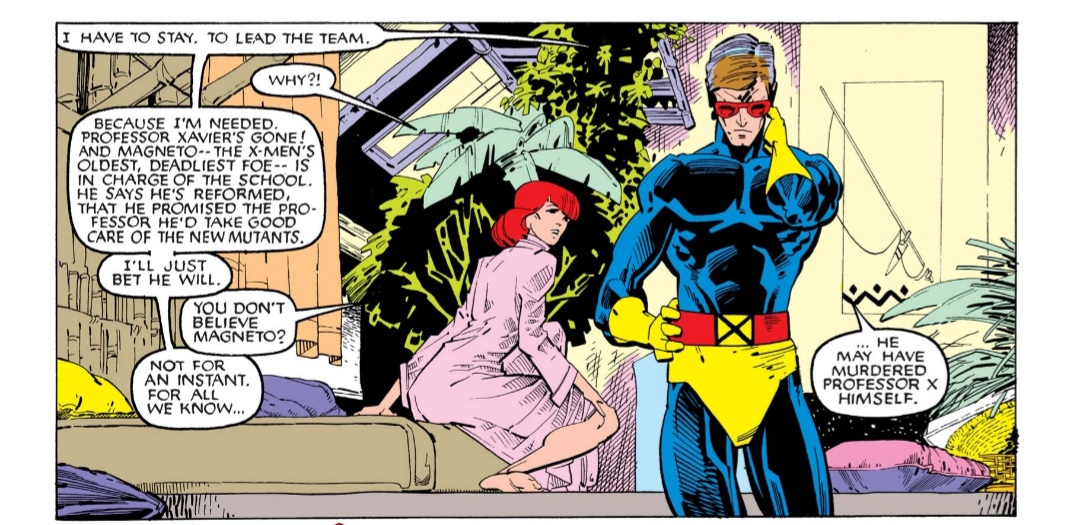

This argument has been made before, and has some traction, but the extent to which it accounts for the success of Claremont’s X-Men is debatable, especially given the broader tradition of similar conflation throughout Marvel comics in the 1960s in general, including X-Men. 4/6

Indeed, conflating social ostracism with systematic and institutional oppression can be seen as part of the Marvel method, given the extent to which Stan Lee and co. utilized this tactic to permeate campus culture in the 1960s (described in Sean Howe's book on Marvel). 5/6

Still, given the numerous representational milestones of the Claremont run, combined with the scale and diversity of the audience who followed (or follow) it, the mutant metaphor is indeed worth exploring as a major point of appeal. 6/6

For more on the book in question: goodreads.com/en/book/show/5…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh