I've been digging into the digitised holdings of the National Archives of Singapore to find posters of the Speak Mandarin Campaign which decimated "#dialect" use in favour of Mandarin. Launched in 1979, here is one of the earliest posters from the same year: (1/16)

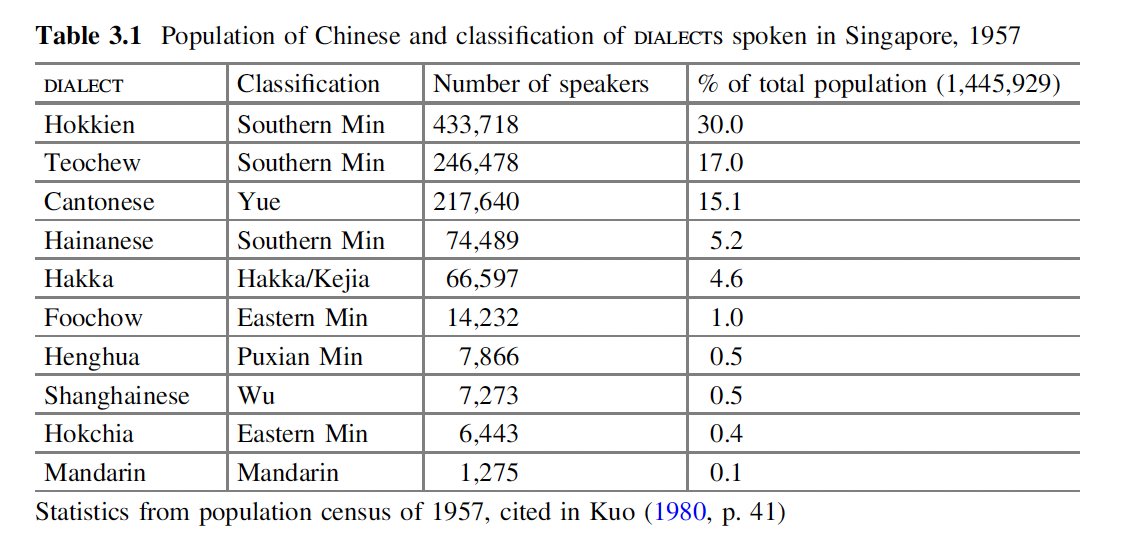

The Speak Mandarin Campaign is the society level expansion of a bilingual education policy that tried to unify a polyphonic Chinese-language soundscape. Dialect broadcasts were banned, for example. You get a sense of this polyphony from this 1957 census (Ding 2016): (2/16)

I wish I had a clearer image of this, but here is a poster from the Ministry of Culture (1981) detailing the Standard Mandarin names of common fish found in wet markets, coupled with English names and pinyin. (Anyone recognise the fish here?) (3/16)

Clearly, there was a targeted campaign against dialect use in markets: here are two similar posters for condiments and fruits. (Till this day, my paternal grandma who can otherwise use Mandarin to communicate will know only the Hokkien/Cantonese words for food items.) (4/16)

This other 1981 poster, I find rather funny and ironic: the fruit store sign reads 每粒八角, using the counter "粒" for fruit—which, as far as I know, is an influence from the Hokkien "liap"—instead of the standard Mandarin "个". (Need people to verify!) (5/16)

Two years later, the campaign slogan for 1983 "华人讲华语,合情又合理"—"Mandarin's In, Dialect's Out" in the campaign's official English slogan—but more literally it translates to: "It is harmonious and reasonable for the Chinese to speak the Mandarin Chinese language". (6/16)

But it is the 1985 slogan that perhaps most explicitly attempts to conflate Chinese ethnicity (华人) with Chinese language (华语), to de-emphasise dialect group identities in favour of the aspirational homogeneity of Chinese-ness across generations. (7/16)

Is this poster from 1986 adopting a Mandarin *first* not *only* approach? Checks out with Lee Kuan Yew's acknowledgement in 1984 that "we do well to recognise that Chinese still have deep emotional ties to dialects", that they "hinder our complete acceptance of Mandarin". (8/16)

With the slogan from 1988—"多讲华语,亲切便利" (Speak More Mandarin, It's Intimate and Convenient)—I wonder how the rhetoric that Chinese is an intimate language was received? I suspect this intimacy is reserved for business Chinese abroad? (9/16)

In any case, composed for the 1988's campaign, this kitschy song urging listeners to use Chinese at the bank, shops, and for business is not going to convince me of the language's intimate value:

"在银行 讲华语

在商店 讲华语

谈生意 讲华语"

(10/16)

"在银行 讲华语

在商店 讲华语

谈生意 讲华语"

(10/16)

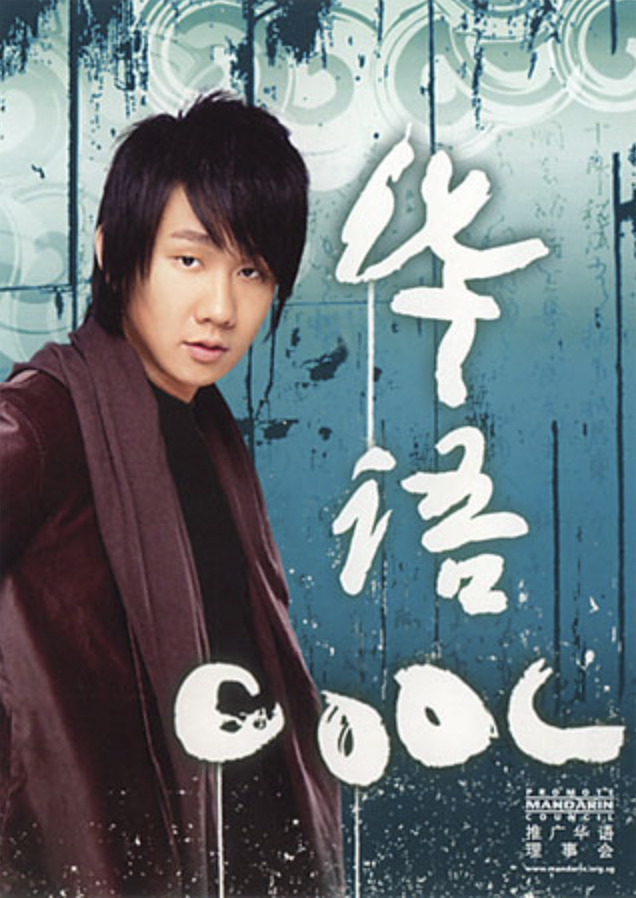

From the 1990s onwards, references to "dialect" begin to disappear from slogans and posters, reflecting possibly the new "threat" of English.

L-R: Speak Mandarin, It's An Asset (1998/9); 华语 COOL! with Mandpop singer JJ Lin (2006); Who's Afraid of Mandarin? (2009/10). (11/16)

L-R: Speak Mandarin, It's An Asset (1998/9); 华语 COOL! with Mandpop singer JJ Lin (2006); Who's Afraid of Mandarin? (2009/10). (11/16)

Yet, recent government public communications in the 2010s has realised the importance of dialects in reaching the elderly. Not since the 1970s, I think, has a whole TV show in dialect been broadcast. Pictured: the show titled "Eat Already?" (2016). (12/16)

And here's my maternal grandma speaking on TV in Hokkien urging seniors to vaccinate against COVID-19. There are videos in Cantonese and Teochew as well. (This has precedence too from the SARS era — bit.ly/3LuZSna)

(13/16)

(13/16)

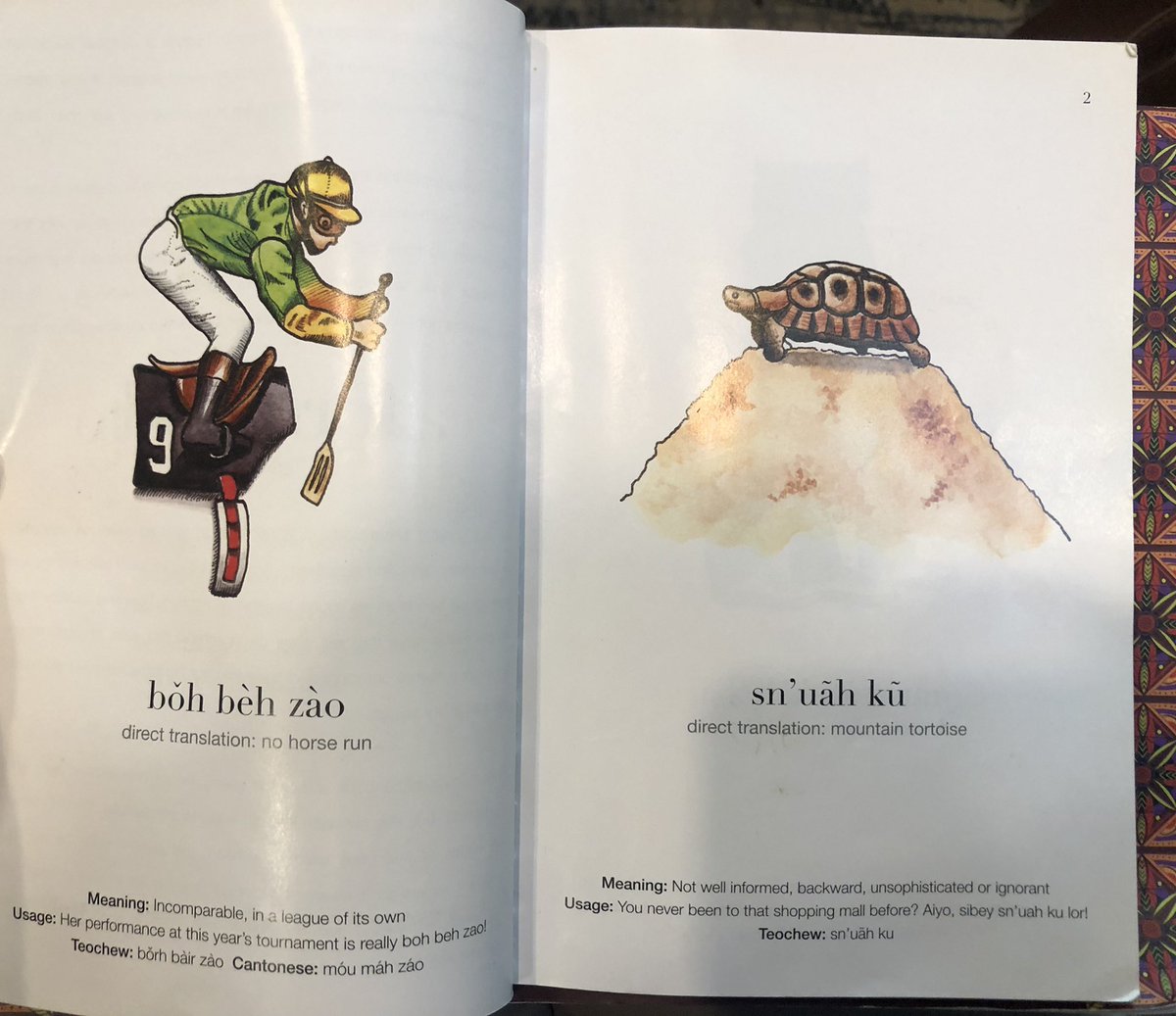

But perhaps we can be heartened that grassroots initiatives like @learndialect, Dialect Classrooms (dialectclassrooms.com), My Father Tongue, etc. have been on the rise recently? (14/16)

Hopefully. Otherwise, to take Hokkien as an example (Ding 2016): "With the current trend of language shift in Singapore, within two generations or so (50–60 years) it will be hardly possible to start conversation in Hokkien with a stranger in public." (15/16)

Back to these posters, I imagine a decade of Singapore plastered with these visual exhortations and feel sad. I couldn't find a 1984 poster but it would have read:

"请讲华语,儿女的前途,操在您手里"

"Speak Mandarin. Your Children's Future Depends on Your Effort Today" (16/16)

"请讲华语,儿女的前途,操在您手里"

"Speak Mandarin. Your Children's Future Depends on Your Effort Today" (16/16)

(Since this thread is taking off, here's a tongue-in-cheek poem I wrote based on something my paternal grandma told me in Hokkien: bit.ly/3uRwMYr. Appears in my upcoming @DiodeEditions chapbook, OF THE FLORIDS, sign up for pre-order updates: bit.ly/3K6flK8)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh