A handful of commodities (🐮🌴🍫☕️) cause a third of all #deforestation, harming millions of forest-dependent people, the climate & biodiversity

A few commodity traders (Cargill, Wilmar, Olam, etc) handle this trade

Here’s what you need to know about their sourcing practices 🧵

A few commodity traders (Cargill, Wilmar, Olam, etc) handle this trade

Here’s what you need to know about their sourcing practices 🧵

The supply chains which move commodities around the world are oft described as an hourglass.

Thousands of farmers supply a handful of commodity traders who in turn supply millions of downstream customers.

Thousands of farmers supply a handful of commodity traders who in turn supply millions of downstream customers.

When downstream companies (manufacturers, retailers) make sustainability commitments, they rely on the traders who supply them to implement these commitments.

Ditto new #DueDiligence legislation which bans the import of products linked to deforestation or human rights abuses.

Ditto new #DueDiligence legislation which bans the import of products linked to deforestation or human rights abuses.

But how much visibility do traders actually have over where their supplies come from?

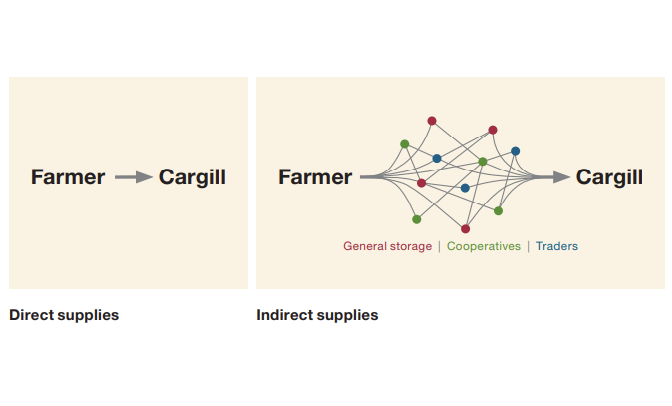

In a new study in @ScienceAdvances, we checked how often traders buy directly from farmers vs how often do they buy *indirectly* from other kinds of middlemen – local traders, aggregators, & cooperatives.

This distinction (direct/indirect) matters, because it’s inevitably harder to identify the source of products (& check for deforestation or forced labor) when your suppliers are removed from the product’s origin.

We used customs records, corporate disclosures, animal movements, farm production data to estimate direct/indirect volumes for 4 commodities where deforestation is a big issue: soy from South America, cocoa from Côte d’Ivoire, palm oil from Indonesia & cattle exports from Brazil

We have three main insights

1. Indirect sourcing via local intermediaries is fundamental to commodity trading, making up 12-44% for soy, 15-90% of palm oil, 94-99% of live cattle and essentially 100% of cocoa.

Commodities often change hands several times before traders take ownership of them.

Commodities often change hands several times before traders take ownership of them.

Indirect sourcing is not something sinister. Commodity trading is mostly dictated by costs and logistics, & historically hasn’t worried about where products came from & how they’re produced.

By definition, commodies are ‘interchangeable with other products of the same type’

By definition, commodies are ‘interchangeable with other products of the same type’

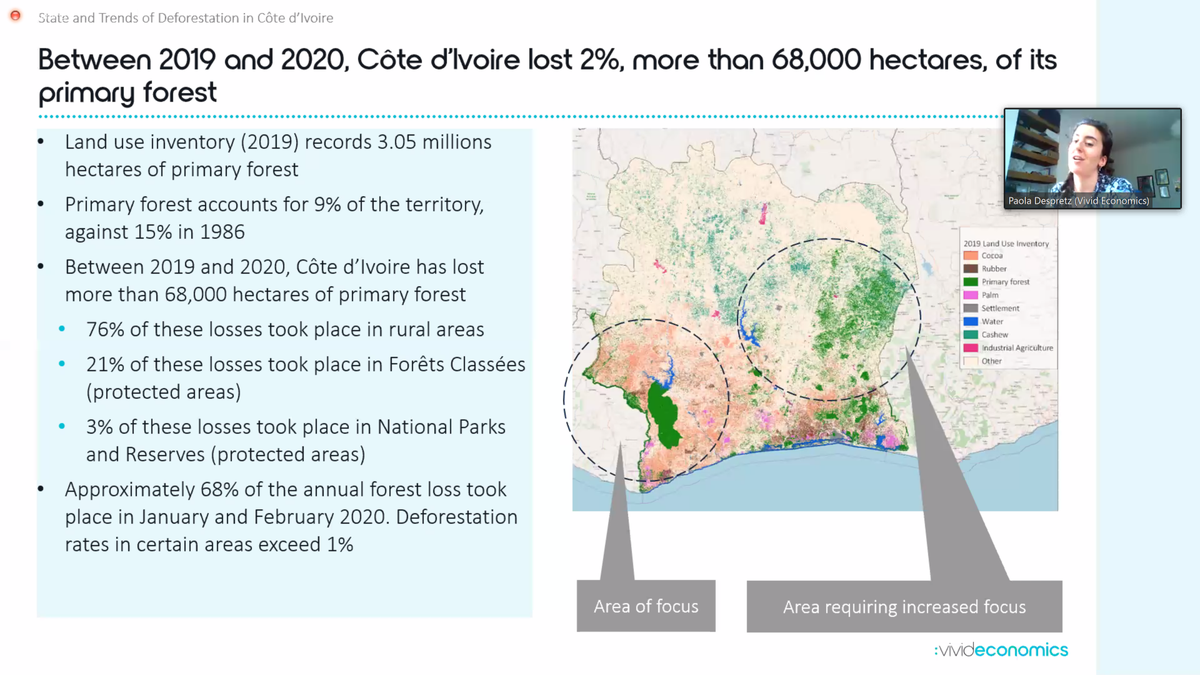

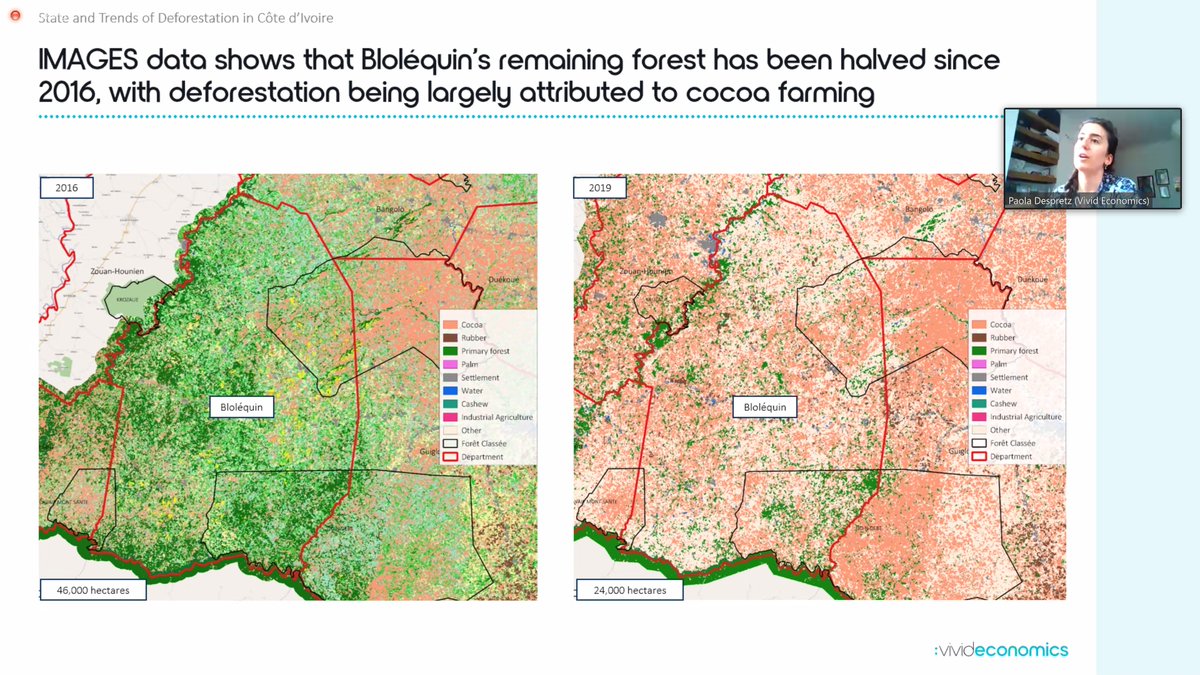

2. Lots of sustainability risks arise among indirect suppliers.

Indirect sourcing poses substantial deforestation risk across all commodities, if nothing else because of its position of low oversight (compared with direct sourcing) & the sheer volumes sourced indirectly.

Indirect sourcing poses substantial deforestation risk across all commodities, if nothing else because of its position of low oversight (compared with direct sourcing) & the sheer volumes sourced indirectly.

Deforestation & other reputational risks are often higher in precisely those parts of the supply chain over which companies have the least visibility.

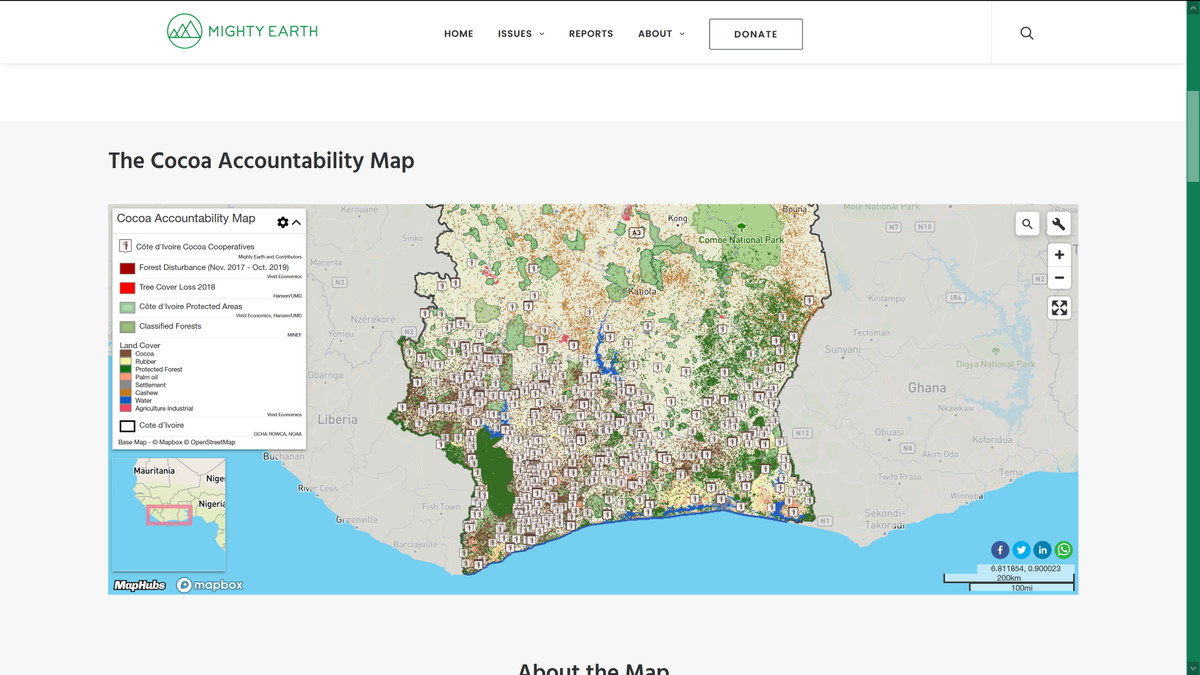

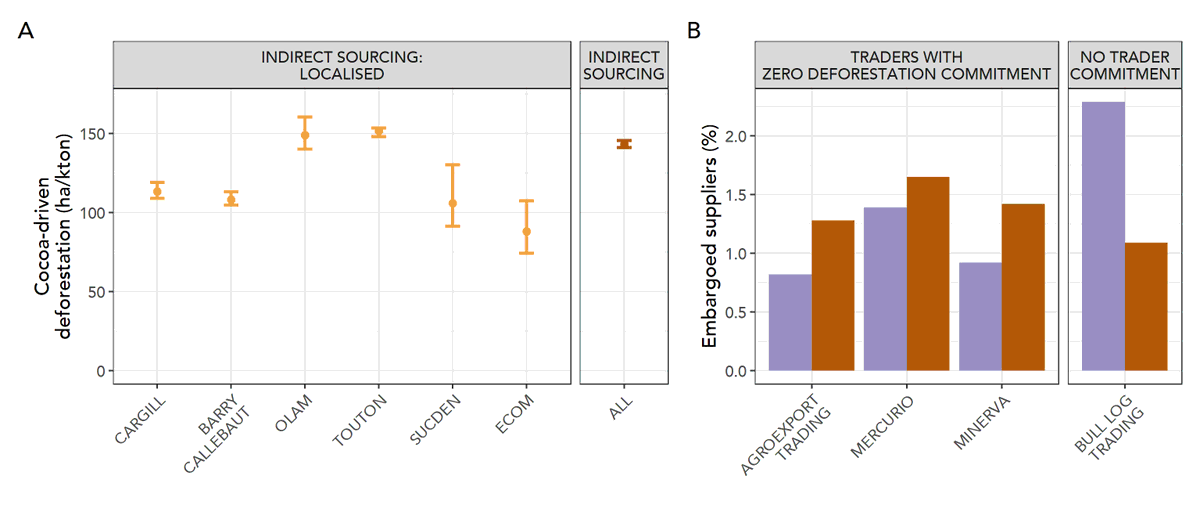

Pulling together the data/evidence is demanding, but we show this using new data for cocoa and cattle supply chains.

Pulling together the data/evidence is demanding, but we show this using new data for cocoa and cattle supply chains.

3.Indirect sourcing is a major blind spot for sustainable procurement efforts

Companies are waking up to the challenge of monitoring indirect suppliers (e.g. they were included in commitments made at the COP), but progress is far from certain! ukcop26.org/agricultural-c…

Companies are waking up to the challenge of monitoring indirect suppliers (e.g. they were included in commitments made at the COP), but progress is far from certain! ukcop26.org/agricultural-c…

In the soy sector, Bunge currently monitors only 30% of its indirect sourcing (vs 100% for direct).

In the cattle sector, meatpackers promise to monitor indirects in 2025 or 2030, but plans are still fuzzy.

In the cattle sector, meatpackers promise to monitor indirects in 2025 or 2030, but plans are still fuzzy.

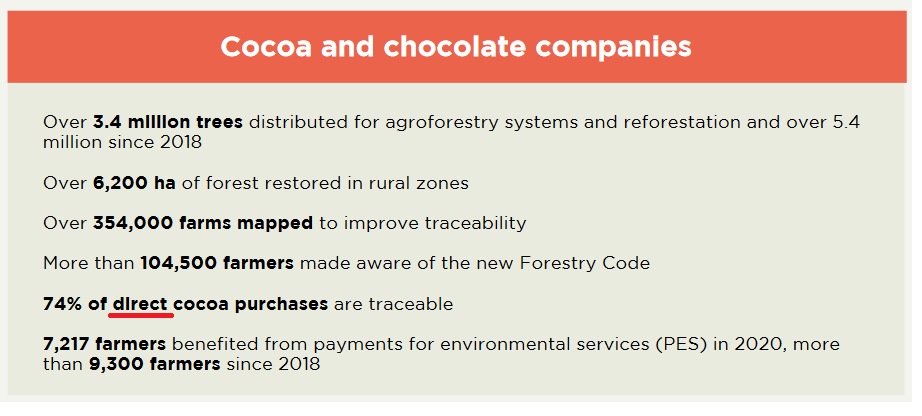

The main sustainability initiative for cocoa, the Cocoa & Forests Initiative, sets targets for traceability of cocoa sourced via cooperatives (which they call ‘direct sourcing’), but is completely silent about other indirect sourcing, though its up to 70% each trader’s sourcing.

Their latest report mentions direct sourcing ca. 20 times, but doesn't mention indirect sourcing even once.

idhsustainabletrade.com/uploaded/2021/…

idhsustainabletrade.com/uploaded/2021/…

On an unrelated note, a textbook definition of greenwashing is where companies place emphasis on ‘observable aspects and negligence of the unobservable aspects’. pubsonline.informs.org/doi/10.1287/mn…

I’ll do a more detailed thread on solutions later this week, but 3 implications are:

1. Producer governments need to promote transparency, publishing key data on supply chains

2. Trading companies must think beyond their own direct supply chains, engaging at landscape-level

1. Producer governments need to promote transparency, publishing key data on supply chains

2. Trading companies must think beyond their own direct supply chains, engaging at landscape-level

3. Sustainability initiatives, such as the CFI, Amazon Soy Moratorium, & Cattle Agreements, need to acknowledge, monitor, and report on indirect sourcing - and ultimately ensure it doesn´t remain a barrier to delivering on sustainability goals

Sharing results with industry & civil society I’ve had two main reactions: our findings are either obvious or enlightening…

Whatever your take, I thank my classy collaborators (@PMeyfroidt, @econ_servation, @vivihrbr, @tobyagardner, @MaironGBL, @HBellfield, @TiagoRe76762750 & co), who helped draw lessons across commodities, something we should perhaps do more of!

Link to the paper here: science.org/doi/10.1126/sc…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh