Happy #JobsDay. Hope you’re staying healthy.

At 8:30 am ET @BLS_gov delivers the most-important signals abt how economy is changing.

Forecasts’ center:

+400K jobs

3.5% unemployment rate, would = pre-pandemic low back to 1969.

At 8:30 am ET @BLS_gov delivers the most-important signals abt how economy is changing.

Forecasts’ center:

+400K jobs

3.5% unemployment rate, would = pre-pandemic low back to 1969.

Biggest question in the economy:

How quickly can we raise supply? Bring more labor & capital to production & boost productivity.

Success means more consumption & lower prices.

Failure means more-painful demand reductions.

How quickly can we raise supply? Bring more labor & capital to production & boost productivity.

Success means more consumption & lower prices.

Failure means more-painful demand reductions.

Will we keep/get COVID under control in US/abroad?

Will employers increase supply by improving job offers fast enough to attract the people they say they want to hire, bring people off sidelines & compensate them for risks/hassles?

Will employers increase supply by improving job offers fast enough to attract the people they say they want to hire, bring people off sidelines & compensate them for risks/hassles?

Relative to pre-pandemic, corporate profits (& margins) have grown at a much faster rate than consumer prices or hourly labor costs.

Many corporations have resources to improve job quality but holding back🧵

Many corporations have resources to improve job quality but holding back🧵

https://twitter.com/aaronsojourner/status/1518618151562395648

The Employment Situation report will be here

bls.gov/news.release/e…

bls.gov/news.release/e…

428K jobs gained last month (mid-Mar to mid-Apr), which coincidentally exactly equals March's revised growth.

-39K jobs in revisions of last 2 months

-39K jobs in revisions of last 2 months

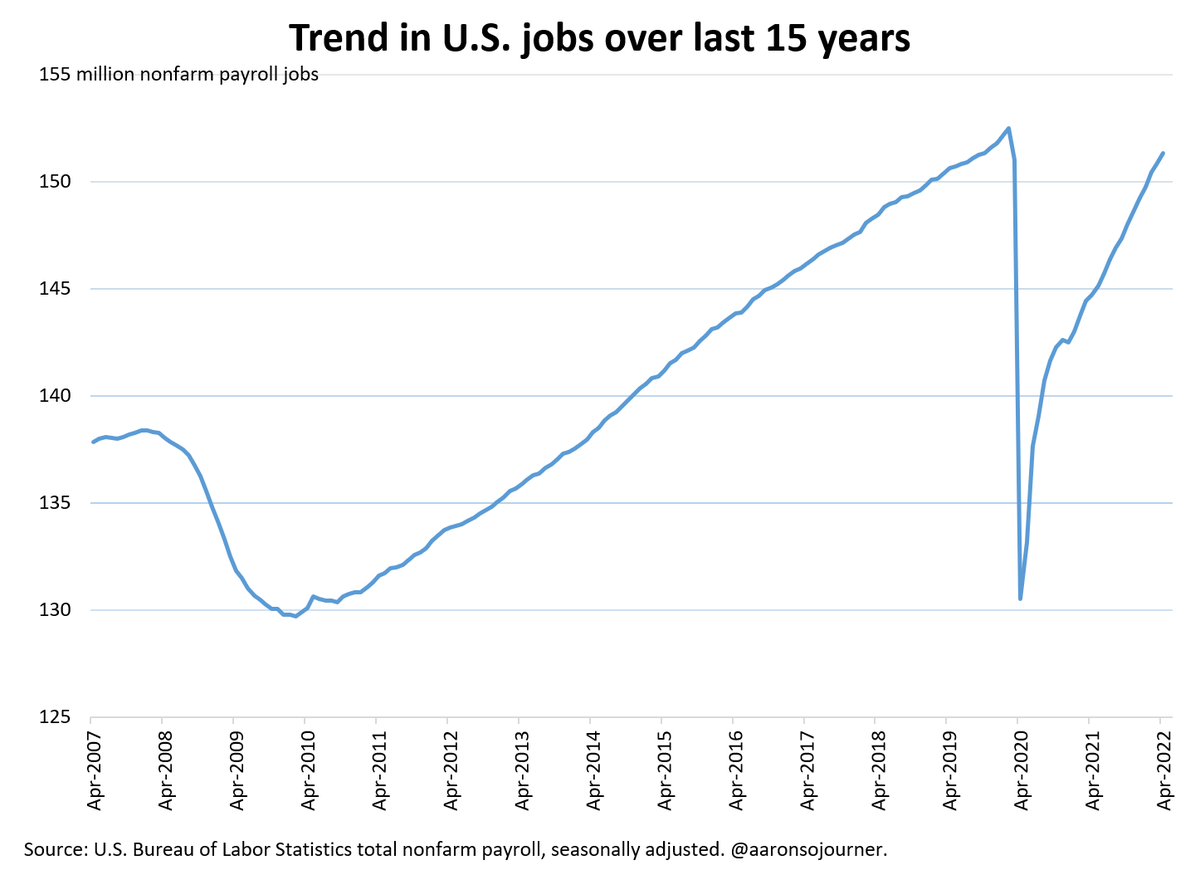

The trend in the number of U.S. jobs over the last 15 years shows that we remain just shy of pre-pandemic levels.

We have had fast, steady growth since Jan 2021, after weakness in late 2020 & job loss in Dec 2020.

We have had fast, steady growth since Jan 2021, after weakness in late 2020 & job loss in Dec 2020.

The trend in over-the-year job growth shows how much faster our recent job growth has been than during the post-Great Recession recovery.

Job growth has decelerated a smidge:

552K/mo over most-recent 12 months

552K/mo over most-recent 6 months

523K/mo over most-recent 3 months

428K this past month

552K/mo over most-recent 12 months

552K/mo over most-recent 6 months

523K/mo over most-recent 3 months

428K this past month

Fiscal policy at all gov't levels slowed economic growth by 2.96 pp in annualized terms in 2022Q1, @BrookingsInst.

Anyone talking about expansionary tax & spending policy has it backwards. We’ve had contractionary fiscal policy for 4 quarters.

Monetary policy shifted down too

Anyone talking about expansionary tax & spending policy has it backwards. We’ve had contractionary fiscal policy for 4 quarters.

Monetary policy shifted down too

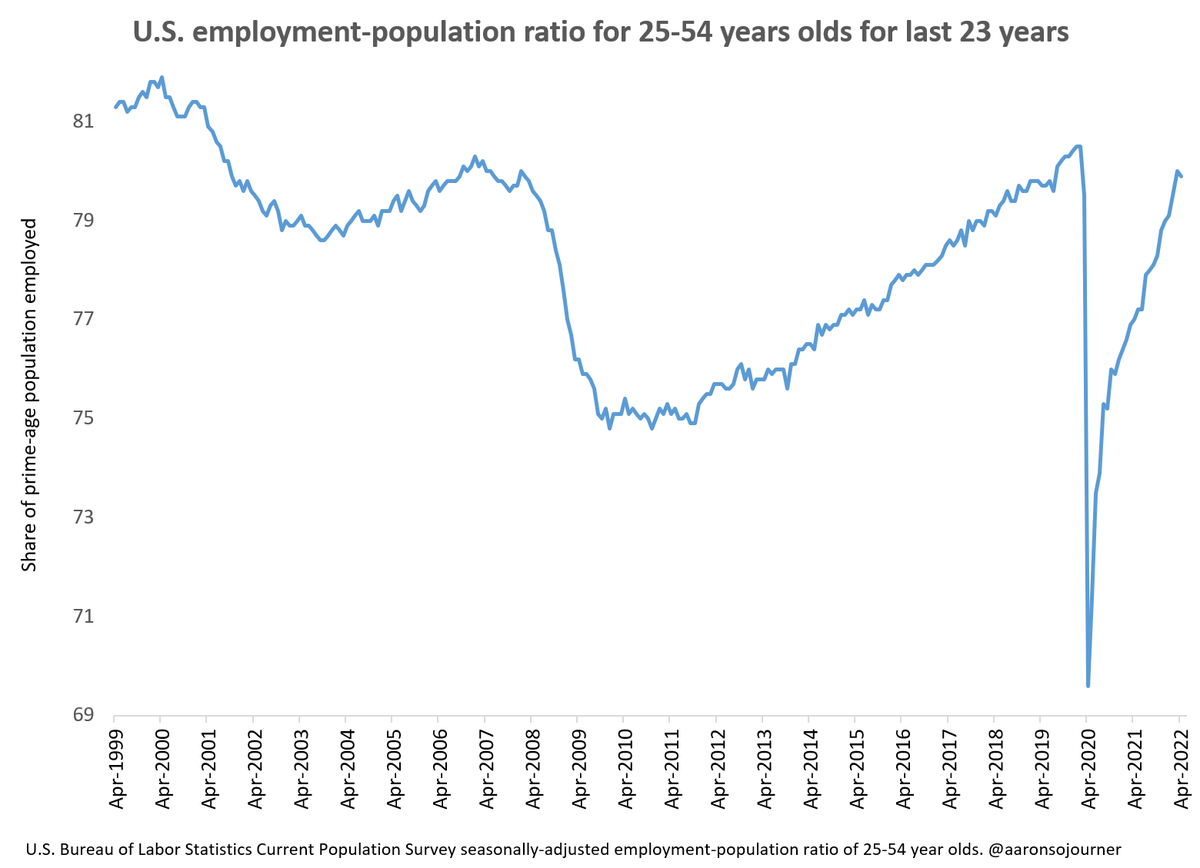

Both the labor force participation rate (LFPR), at 62.2%, and the employment-population ratio (EPOP), at 60.0%, were little changed over the month.

These measures are each 1.2 percentage points (pp) below their February 2020 values.

These measures are each 1.2 percentage points (pp) below their February 2020 values.

Prime age (25-54 years old) employment to population ratio is an important measure of core labor market strength, omits people on the fringes of work.

It ticked down 0.1 pp to 79.9%, 0.6 pp below its pre-pandemic level. There's still room to improve here.

It ticked down 0.1 pp to 79.9%, 0.6 pp below its pre-pandemic level. There's still room to improve here.

The missing employment is no longer following clear patterns by race-ethnicity and gender.

Black men are estimated to be employed at greater rates than pre-pandemic but these estimates are somewhat noisy and a big population adjustment using 2020 Decennial shift lots in Jan.

Black men are estimated to be employed at greater rates than pre-pandemic but these estimates are somewhat noisy and a big population adjustment using 2020 Decennial shift lots in Jan.

What ages account for +2.4 million out of labor force & not wanting a job now?

Increase in the number of older Americans (55+) in this group accounts for 90% of its rise. Early retirements? COVID concern? Grandkid care?

Number of young folks in the group actually -110K.

Increase in the number of older Americans (55+) in this group accounts for 90% of its rise. Early retirements? COVID concern? Grandkid care?

Number of young folks in the group actually -110K.

That’s the extensive quantity (Q) margin. Intensive Q margin is average hours.

Average workweek hours for private sector steady at 34.6 hours. Has started normalizing after brutal pandemic plateau.

Average workweek hours for private sector steady at 34.6 hours. Has started normalizing after brutal pandemic plateau.

Because the temporary-help industry is the leading edge of flexibility in jobs, change in its employment level can give a leading sense of changes in broader market. It tends to go negative before recessions (and other times).

It's down near 0 for 2 months, suggesting softening.

It's down near 0 for 2 months, suggesting softening.

In sum, looks like fast demand growth that we've seen is slowing due to brakes from fiscal & monetary policy, energy prices, & supply chains.

Still some slack but not easy to employ, relying on unretirements & demand for those with less formal educ (yay, Infrastructure Law!)

Still some slack but not easy to employ, relying on unretirements & demand for those with less formal educ (yay, Infrastructure Law!)

Gotta go downtown. Annual @SOLE_Labor_Econ meetings in Mpls this year. Hope to meet you if you're here.

https://twitter.com/aaronsojourner/status/1522434872647823360

Last thing. @BLS_gov does amazing work to create timely, accurate info about America's working families, a huge public good.

They are there for us & we need to show up for them. If you are a labor economist or care about workers & employment, follow & join @Friends_of_BLS.

They are there for us & we need to show up for them. If you are a labor economist or care about workers & employment, follow & join @Friends_of_BLS.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh