Thread: How Russia Defeated Napoleon

Napoleon's doomed invasion of Russia in 1812 is an iconic moment in world history. Most people know the general premise, that Napoleon's army was forced to flee the Russian winter. But why did this campaign doom Napoleon? (1)

Napoleon's doomed invasion of Russia in 1812 is an iconic moment in world history. Most people know the general premise, that Napoleon's army was forced to flee the Russian winter. But why did this campaign doom Napoleon? (1)

There's no doubt that Russia's strategy, orchestrated by War Minister Barclay de Tolly, was ideal. The Russian army retreated deep into the interior, forcing Napoleon to chase them hundreds of miles before they finally offered him battle at Borodino, near Moscow. (2)

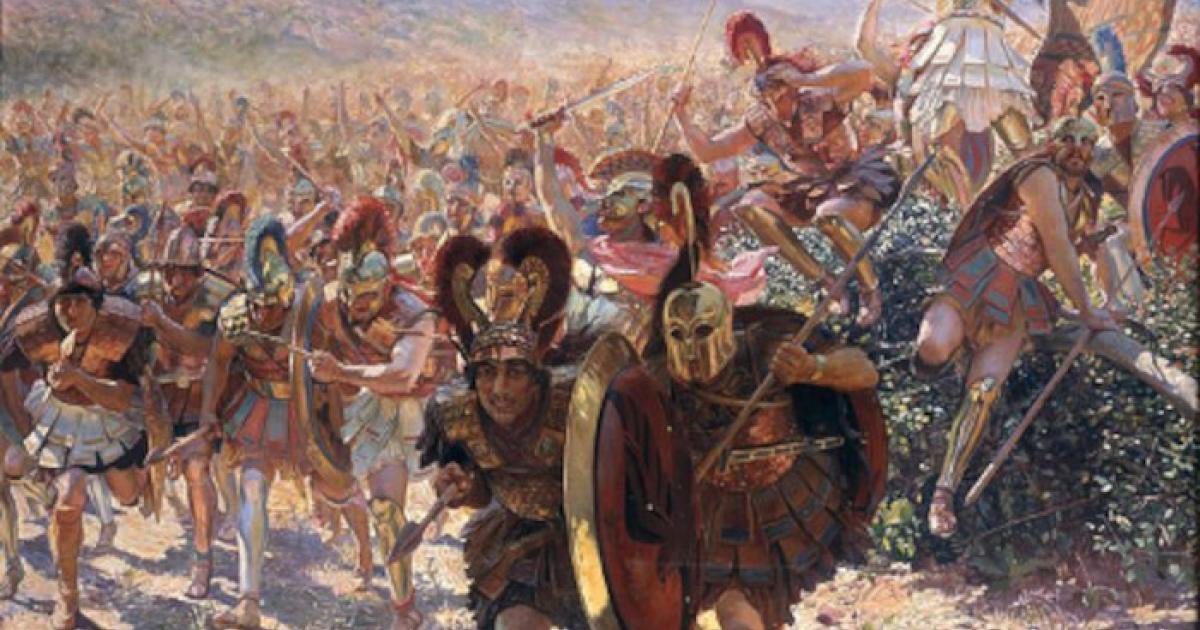

Borodino was a colossal battle - the single bloodiest day of battle in Europe's history, until the First World War. However, it ended with a stalemate and the Russian army was able to retire bloodied but intact. Napoleon was now unable to achieve any major strategic aims. (3)

The Russians abandoned Moscow, and it was soon torched. With the Russian army intact and Tsar Alexander I refusing to negotiate, Napoleon faced the prospect of wintering deep in the hostile Russian heartland, far away from his own capital. So, he bailed. (4)

Napoleon's army frantically retreated from Russia along a barren, freezing path, crumbling from hunger, sickness, wounds, desertion, and Russian cavalry hounding the flanks. In the end, Napoleon lost in excess of 400,000 men in Russia.

But this isn't the important part! (5)

But this isn't the important part! (5)

Napoleon's invasion force was surprisingly light on French soldiers. He mustered over 600,000 men, but less than half were actually French. The rest were drawn from various satellite and client states around Europe, including a huge number of Poles. (6)

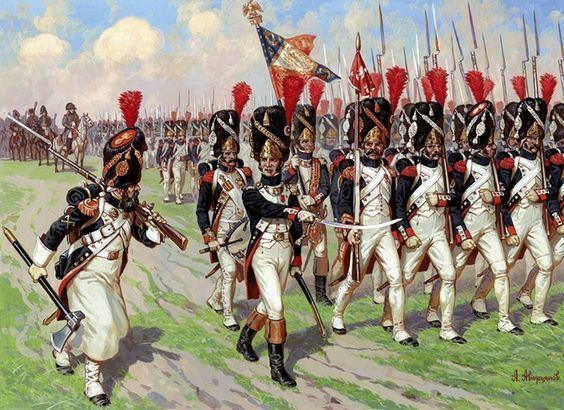

Furthermore, Napoleon's Imperial Guards - the best infantry units in Europe at the time - were withheld from battle at Borodino. Napoleon commented that he did not want to have them "blown up" thousands of miles from Paris. This proved very important. (7)

Due to the multinational composition of his invasion force, and the decision to keep the Imperial Guards in reserve, Napoleon was far from a dead man walking in 1813. By the spring, he already had a fresh force of over 200,000 men active in Germany. (8)

So, why was the Russian invasion so catastrophic for Napoleon? After all, the total number of French casualties in the campaign was lower than the losses they inflicted on the Russians - they too were badly chewed up. So what was the difference maker?

Horses. (9)

Horses. (9)

Napoleon's army lost an enormous number of horses in Russia, some in battle, but largely to hunger, as they were unable to provide feed for them. Cavalry were notoriously difficult and expensive to replace, and after 1812 Napoleon was never able to replenish his cavalry arm. (10)

So by the middle of 1813, Napoleon had actually replaced French manpower losses and was fielding perfectly adequate infantry forces, but his cavalry remained permanently weak. Twice, this would prove absolutely decisive. (11)

Cavalry was critical in Napoleonic warfare as the weapon of exploitation - used as the hammer to inflict huge casualties after the enemy's formations were wrecked, and to block retreats. Napoleon now lacked the ability to consolidate and exploit victories. (12)

In May 1813, Napoleon fought two battles against combined Prussian-Russian armies - one at Bautzen and one at Lutzen - and won them both. However, his lack of cavalry prevented him from pursuing and trapping the allied armies, and twice they escaped with modest casualties. (13)

Insufficient cavalry prevented Napoleon from destroying these allied forces in May, and allowed them to remain intact and regroup with the Austrians for the Battle of Leipzig - which finally ended Napoleon's control of Central Europe and set the stage for his final fall. (14)

The lesson we draw from this is about the synergistic use of arms, and the deceptive nature of numbers in war. Napoleon's ability to regenerate his infantry ultimate meant nothing in the absence of adequate cavalry forces. (15)

We saw something similar happen to Germany in World War Two. By 1944, the German forces on the Eastern Front were numerically quite close to those that they brought 1941, but they were materially far weaker due to insufficient air, armor, and artillery. (16)

Of course, Napoleon made a brief resurgence in 1815 before being defeated for good at Waterloo. This has led "Waterloo" to become a figure of speech for someone's downfall. The irony in this is that Waterloo was not Napoleon's Waterloo.

His Waterloo was Borodino. (17)

His Waterloo was Borodino. (17)

Bonus: A portrait of Tsar-Saint Alexander I

He was an excellent wartime leader for Russia, kept his head during Napoleon's invasion, and singlehandedly created the coalition that defeated him. He was also a sensitive and soft hearted man.

He was an excellent wartime leader for Russia, kept his head during Napoleon's invasion, and singlehandedly created the coalition that defeated him. He was also a sensitive and soft hearted man.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh