Teutonic Knights are known as fierce crusaders who fought against the pagans in the Baltics.

But in 1312 they were under a serious investigation by the Pope for allegedly practicing paganism themselves!

How did this happen and was there some truth to it?

Let's explore!

THREAD

But in 1312 they were under a serious investigation by the Pope for allegedly practicing paganism themselves!

How did this happen and was there some truth to it?

Let's explore!

THREAD

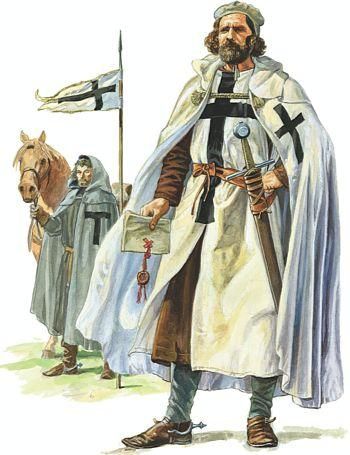

Teutonic Knights were one of the monastic military orders that emerged from the crusades. They combined monastic religious vows of poverty, chastity and obedience with military service, serving as a brotherhood of warrior monks. At the time they presented an ideal of Christendom.

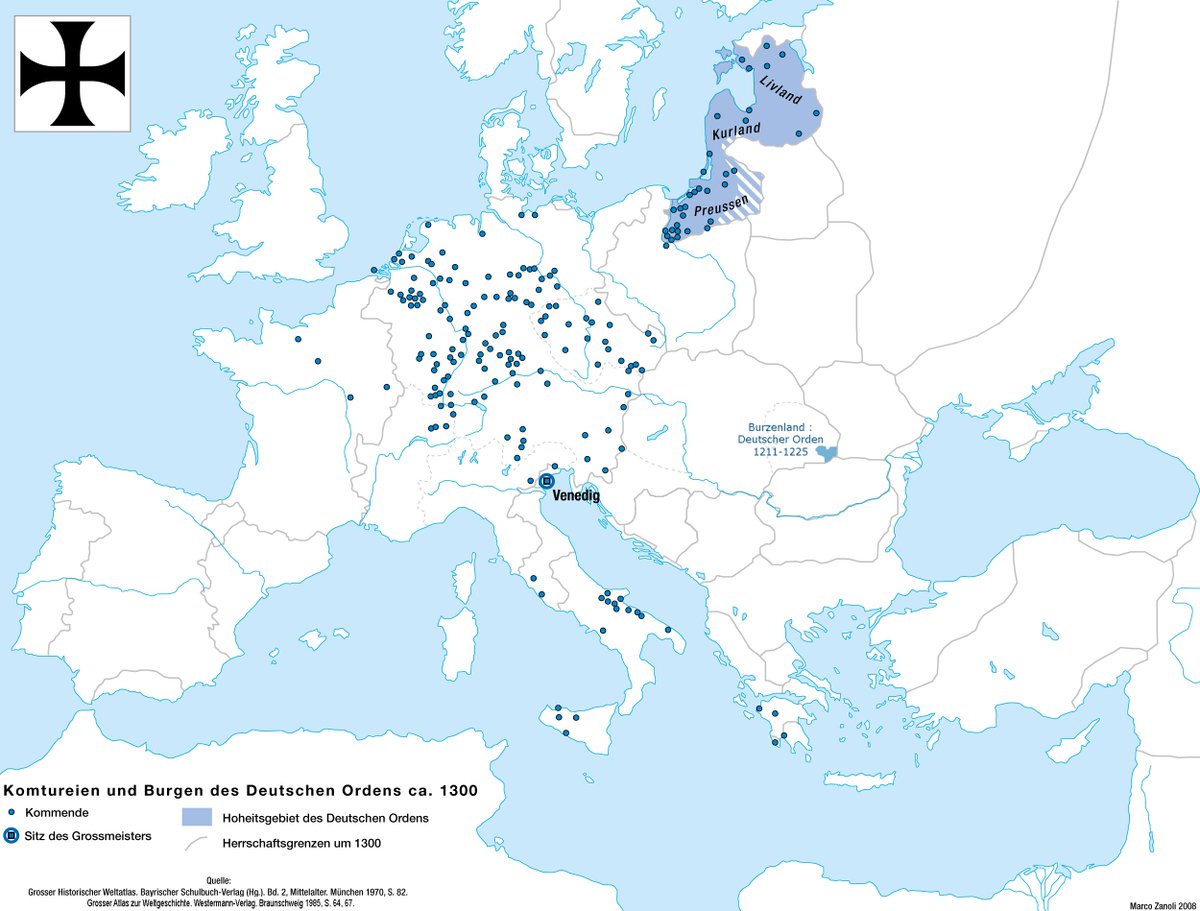

Such monastic military orders developed spontaneously during the crusades in the Holy Land where religious orders had to assume a militaristic role to help defend themselves and fellow Christians. They would eventually grow into big institutions with chapters all over Europe.

Compared to the other two major monastic military orders, the famous Templars and the Hospitallers, the Teutonic Knights originated a bit later in late 12th century. They were created out of a practical necessity to have an order for German-speaking knights specifically.

The Teutonic Order had humble beginnings in the shadow of the bigger orders of Templars and Hospitallers. It would be only under the rule of Grandmaster Hermann von Salza from 1210 to 1239 that the order would become significant and was granted equal status as the other two.

The social background of Hermann von Salza was typical of that of a Teutonic Knight, originating from the lower nobility of Thuringia of the ministerialis class raised up from serfdom. In the future most Teutonic Knights would be ministeriales, commonly from Thuringia and Saxony.

The fact that someone of such lowly origins could rise to such prominent position was a specific characteristic of these religious military orders noticed by st. Bernard, "There is no distinction of persons among them, and deference is shown to merit rather than to noble blood."

Hermann von Salza would enjoy great prestige in Europe as he became a friend and personal councilor of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II while also having a great relationship with his rival Pope Honorius III. This enabled him to serve as a mediator between the two of them.

It was through Hermann von Salza and his influence in the Holy Roman Empire that Teutonic Order would become more involved in Europe. In 1211 King of Hungary Andrew II requested the Teutonic Knights to come to Transylvania to help defend it against the incursions of pagan Cumans.

The Teutonic Order obliged and fought against Cumans in Transylvania with great success. This was in line with crusader ideology as crusades were not just overseas expeditions to the Holy Land but also involved organizing the defense and expansion of borderlands of Christendom.

Meanwhile the Teutonic Order still continued to have a significant presence in its birthplace, the Holy Land, and its knights participated in all the major battles against the Muslims there in the 13th century. This was crucial for the order's prestige and reputation.

But it was the success of Teutonic Order in Transylvania which showed that at the time, the monastic military orders represented the very elite of European warriors. Though few in numbers, they were highly skilled, dedicated and fought together cohesively as a brotherhood.

Furthermore they possessed resources, powerful horses and weapons and built strong fortifications. In Eastern Europe they were still way above the local military organization. But this was also a problem and the local nobility of Hungary saw them as rivals and complained.

In 1225 the Teutonic Order had to leave Hungary after complaints from nobility. However a new request would soon come from Poland. Konrad I of Masovia requested the Teutonic Order to fight against the pagan Prussians who were pestering Catholic Polish lands.

This time the Teutonic Knights didn't want a repeat of the Hungarian situation and wanted a guarantee that whatever they would conquer from the pagans would remain their property. The Papal bulls confirmed that and they set out to successfully conquer pagan Prussia.

This was a perfect situation for the Teutonic Order. They had a blessing for their expansion by both the Emperor and the Pope and the Baltics were close to their recruitment base in German-speaking lands. They could create their own crusader state in the Baltics.

However the conquest of Prussia was tough. The old Prussians were a warrior race of Baltic language speaking pagans and even after Teutonic Knights had initially conquered them, they staged several bloody uprisings. The Teutonic Knights conquered these lands after hard struggle.

But at the same time this only meant more prestige for the Teutonic Order. These Prussians had troubled neighboring Christians for a long time and it was only through Teutonic Knights that these ferocious pagans had been tamed. Their crusade was hailed as a great success.

Furthermore there were other pagans left that Teutonic Knights had to fight against, the pagan Lithunians who were carving out a powerful state of their own. The border between them and the Teutonic Knights would witness constant brutal war for more than a century.

The military might of Teutonic Knights also opened up way for German merchants and settlers. They founded cities and increased trade with wealthy Hanseatic cities. The State of the Teutonic Order was becoming powerful. It would soon become a rival to its Christians neighbors.

Teutonic Knights would end up fighting not only against pagans but also against other Christians. This led to them being connected to German expansionism by modern nationalist propaganda. But this overlooks an important fact. One of their big conflicts was with other Germans.

The conflict that significantly damaged the reputation of the Teutonic Knights and led to them being accused of paganism in 1305 and then investigated in 1312 was with German burghers of Riga and their Archbishop. From 1297 to 1330 Teutonic Knights were in open war with Riga.

To understand this conflict we need to go further back because the Teutonic Knights were actually not the first Germans to crusade in these lands. The German Bishops of Riga had already been to the Baltic before them. Decades earlier they led the Livonian crusades.

North to the lands controlled by Teutonic Knights an ecclesiastical state called Terra Mariana had already been established in 1207 by Bishop of Riga Albert on the territory of modern day Latvia and Estonia and subjected to the Holy See. These lands were also known as Livonia.

In order to fight the local pagans, Bishop Albert of Riga had already established a monastic military order of his own in 1202. It was known as the Livonian Brothers of the Sword. But they did not have nearly the same prestige as the Teutonic Knights who looked down on them.

These Livonian Brothers of the Sword were supposed to serve the Bishop directly as his vassals. But they started to increasingly ignore him and were doing their own thing. This created a tense situation where Pope himself criticized Brothers of the Sword for their actions.

In 1236, the Livonian Brothers of the Sword suffered a devastating defeat to the pagans at the battle of Saule. What was left of them was incorporated into the Teutonic Order a year later in 1237. They were reduced to being a branch of Teutonic Order called the Livonian Order.

By incorporating the Livonian Order, the Teutonic Order inherited its military structure and domains in Livonia. This meant that they now had a presence there and vastly extended their influence in the region. But they also inherited the conflicting situation with the Bishop.

This created a situation where Teutonic Order was autonomous in Prussia but technically subjected to the Archbishop of Riga in Livonia. Needless to say, just like the Livonian Brothers before them, the Teutonic Knights did not feel like listening to the Bishop too much.

It would take a while for things to escalate to an open war but by the end of the 13th century the burghers of Riga and the Teutonic Order went to war with each other. The Archbishop of Riga supported the burghers even though they allied with the pagan Lithuanians.

In this context the accusations of heresy and practicing paganism made in 1305 by the Archbishop of Riga look like a cynical move in a power struggle. They were in war with the Order so he accused them of being some sort of heretics. But it was more complex than this.

At the time these accusations were made against Teutonic Knights accusations of heresy were also made against Templars. Following the fall of the last crusader stronghold of Acre in 1291, the crusades in the Holy Land failed and monastic military orders were easily scapegoated.

The entire purpose of these religious military orders was put into question. They were also seen as dangerous secret parallel societies that undermined other ruling powers. When you look at this map you can understand why King of France Philip IV destroyed the Templars in 1307.

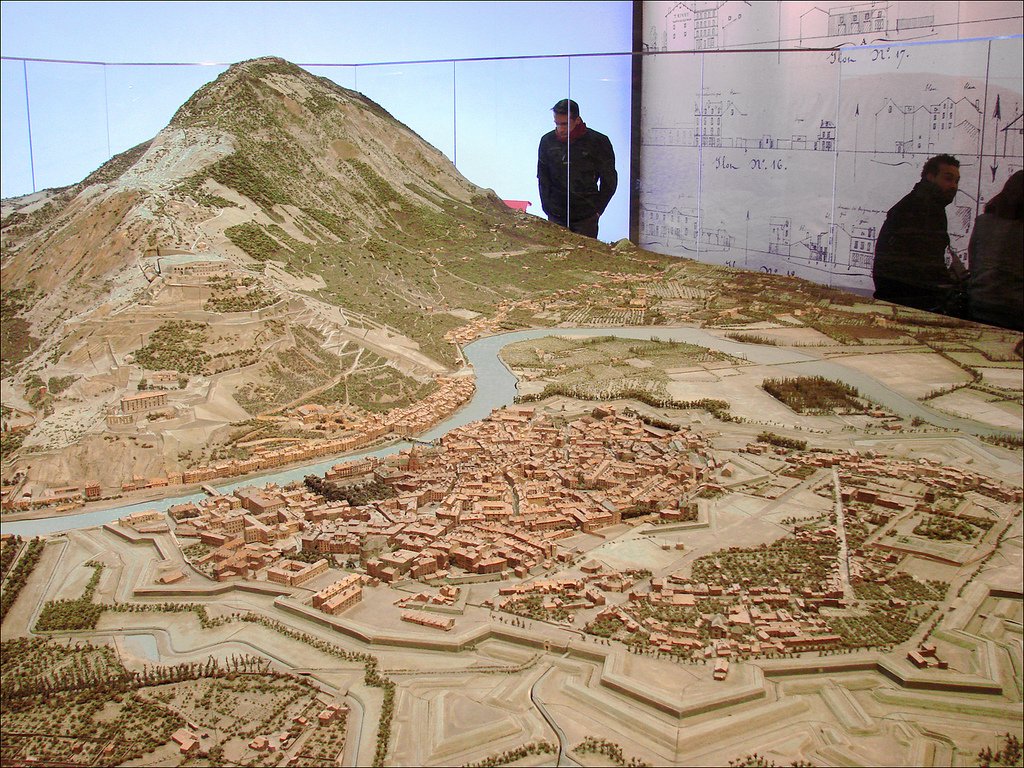

Following the fall of Acre the Teutonic Order transferred the headquarters to Venice hoping for a new overseas crusade. But following what happened to the Templars, they finally moved them to Marienburg in Prussia in 1309. This symbolized the increasing isolation of the Order.

However unlike the Templars the Teutonic Knights were not in danger of being destroyed. They also had a legitimate reason for existence in the eyes of Christendom as fighters against paganism. That's why the accusations of paganism seem absurd at the first glance.

Heresy seems more plausible. The Teutonic Order had to redefine itself and justify the existence of their unusual state. By doing this they started to develop an ideology that increasingly depended more on Biblical justifications and their own interpretation.

The Teutonic Order started developing a very aggressive and warlike interpretation of Christianity based on Old Testament. This required to paint their enemies, the pagans, as the literal devil and their struggle against them as the ultimate struggle of good and evil.

The problem is that too many people including historians take this demonization of pagans literally without understanding the ideological reasons behind it. Teutonic Order had to promote this in order to justify its legitimacy and existence as a peculiar crusader state.

The Teutonic Order was dependent not just on its own German recruits but also on volunteer crusaders from Western Europe who joined specific campaigns. They improved the standing of Teutonic Order in European politics and its prestige while also providing military aid.

So playing up the crusading aspect and vilification of the pagans was a crucial aspect of how Teutonic Order had to sell itself to Christendom. They were offering a safari like experience to prominent French and English nobles who came to the Baltics to hunt pagans.

But the actual military defense of the State of the Teutonic Order was actually dependent on the natives. The war in the Baltics consisted of raids into enemy territory through the wilderness of the no man's land. It was a different type of war than in the West.

In these circumstances, the Teutonic Knights had to rely on their local pagan Baltic auxiliaries who knew the terrain and could defend the frontier as well as conduct raids into enemy territory. Promises of plunder lured many into taking part in campaigns.

In Prussia, the Teutonic Knights had successfully integrated the pagan Prussians into their society despite the uprisings. The Prussian nobility in particular intermarried with Germans and created an upper class. While nominally converted to Christianity, pagan beliefs remained.

In Livonia the Teutonic Knights had control over an impressive defensive wall of castles in Livonia. But they were few in numbers and had to also rely on local Baltic peasants and were closely connected to them. These peasants kept many of their old traditions and pagan beliefs.

Reality paints a different picture from how Teutonic Knights tried to represent itself. They were rather pragmatic when dealing with native population and their pagan beliefs. In some instances they even respected the rights of their subjects to own their own sacred forests.

So the idea that Teutonic Knights picked up some pagan beliefs and practices from their native subjects does not seem so far fetched at all. After all they were in close contact and fought side-by-side and campaigned together. These accusations actually were not without basis.

Historian Kaspars Kļaviņš has actually made great research in his article The Ideology of Christianity and Pagan Practice among the Teutonic Knights where he studied the texts of Teutonic Knights where they themselves write about conducting specific pagan practices.

For example one of the accusations made against Teutonic Knights was that they believed in fortune telling. In the Livonian Rhyme Chronicle, written and read by the Teutonic Knights, there are instances where it seems the knights did indeed practice fortune telling.

In a joint expedition of Knights and the pagans it seems that both were glad with the omens in a pagan way. "Their oracle sticks had fallen propitiously, and their birds had sang favorably, and from all this they had concluded that everything would go well for them."

In the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle credibility is also given to story how a Lithuanian commander rightly predicted events from a shoulder bone. "He looked at a shoulder bone and his heart sank... Now bones have since lied to many a man, but they did not lie to Lengewin."

Another pagan practice that Teutonic Knights themselves wrote about doing was sacrificing animals and weapons to God. They write how after a successful battle with Lithuanians, Teutonic Knights "divided the weapons and horses equally, and a share was set aside for God in heaven."

A similar sacrifice was made by Teutonic Knights after a successful raid into pagan lands. "With the counsel of his brothers, the master gave a part of the booty to our Lord, because he had given them a safe journey. He had earned His share, and they gave Him weapons and horses."

Another accusation of paganism was that the Knights had killed their badly wounded men and burned their bodies. Again the Livonian Chronicle of Herman of Wartberge confirms how the Teutonic Knights burned 25 of their own warriors killed in battle during campaign in Lithuania.

By examining the literature produced by the Teutonic Knights we can see that these accusations of pagan practices actually had a lot of substance. But this does not mean the Teutonic Knights ceased being Catholics. They just started creating their own version of Catholicism.

The Teutonic Knights were ultimately cleared of accusations but damage to their reputation remained. They would win the war against the city of Riga but the internal conflicts in their state remained.

They remained an unusual state with a peculiar interpretation of Christianity.

They remained an unusual state with a peculiar interpretation of Christianity.

In the next thread on Teutonic Knights I will examine more closely just how exactly this specific interpretation of Christianity looked like and what kind of men were attracted to the Order.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh