Q. What links the Scottish industrialist🏴, the Spanish aristocrat 🇪🇸, the sleepy Ayrshire village 🏘️, aviation firsts 🛩️, and this date in history📅❓

A. Let's follow the thread and find out.🧵👇

A. Let's follow the thread and find out.🧵👇

The Scottish industrialist in question is James George Weir, of G. & J. Weir Ltd., that great survivor of Clydeside engineering who built (and still build) pumps for the world. (📷Aeroplane magazine archive)

James George was the son of James Weir snr., who with his brother George had founded the G. & J. Weir business in Liverpool before returning to Glasgow and making their fortune building feedwater pumps for the Clyde shipbuilding industry.

James G. and his older brother William D. Weir inherited the business and took it from strength to strength. William would become a titan of British industry, Viscount Weir, and increasingly a public servant, being made Lloyd George's Director of Munitions in Scotland in 1915.

Weirs - based at the Holm Foundry in Cathcart - turned over their industrial capacity to the war effort, producing munitions and getting into aircraft manufacturing. William joined the Air Board in 1916, was knighted in 1917 and joined the Air Council.

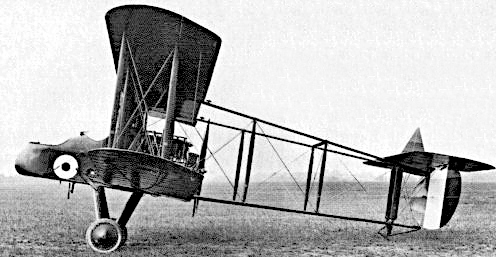

Weirs production included the Royal Aircraft Factory FE.2b fighter. It was William who steered the company at this time, but younger brother James G. was likely an influence - in 1910 he was awarded only the 24th pilot's licence in the UK by the Royal Aero Club.

James G. was already in the army at this point as a volunteer officer in the artillery, and on the outbreak of war in 1914 had himself transferred to the nascent Royal Flying Corps, the fore-runner of the RAF.

For his wartime service, James G. was knighted Order of St. Michael and St. George and made CBE in the UK, Officer of the Order of the Crown by Italy and Officer of the Légion d'Honneur by France.

We turn now to the Spanish aristocrat; Juan de la Cierva y Codorníu, 1st Count of la Cierva. Cierva was the son of the Spanish war minister, and spent his childhood obsessed with building gliders, progressing to an aeroplane built from wreckage and a bar counter.

Cierva took a civil engineering degree and in 1919 he began to seriously experiment with what he would become famous for; rotary wings, specifically the Autogiro. By 1923, Cierva was ready and made the first flight in his "flying windmill" (📷 US Centennial of Flight)

An autogiro looks a bit like a plane and a bit like a helicopter, indeed it's a halfway house between the 2. It uses an engine and propellor to give it forward thrust, and an unpowered rotating wing (driven by the airflow over it) to provide lift.

An autogiro cannot however take off or land vertically, or hover, like a helicopter, but it can safely do all these things very slowly.

Cierva continued to develop and tinker and spent his personal fortune on improving his designs. The C.6 model was funded by the Spanish military, and in 1925 was seen in action by the aviation daft James G. Weir.

Brigadier-General James G. Weir was by then the Director General of the Technical Department of the RAF, as well as a director of the Weir company, and had the foresight to see the promise in the Spanish contraption.

James G. ingratiated himself with Cierva, and with Air Ministry backing and the financial and industrial muscle of G. & J. Weir Ltd., invited the Spaniard to the UK to set up the Cierva Autogyro Co. Ltd. to continue his work.

Weir was a majority shareholder and joint director with Cierva. The new company did not have its own facilities, so subcontracted construction to A. V. Roe & Company Ltd., better known to the world as Avro - of Lancaster bomber fame.

With the backing and encouragement of Weir and access to the support and facilities of the British aviation industry, Cierva lost no time in producing new models, each an incremental improvement on the one before.

The new model was ready as soon as 1926 - the C.8 (based on the C.6 that captivate Weir). With Weir's influence, the first customer was the Air Ministry, and Cierva himself delivered it personally by making the first ever cross-country rotororcraft flight in the UK

Customer number 2 was one Air Commodore James G. Weir. Weir's personal autogyro was registered G-EBYY and can still be seen hanging in the French Air and Space Museum (📷CC By-SA 3.0, Pline)

Weir entered the machine in the 1928 King's Cup air race and used it to make demonstration tours, flying it himself sometimes. It made the first crossing of the English Channel by a rotary winged aircraft on 18th September 1928, which is why it ended up in a French museum.

In 1932 the Cierva company moved to new facilities at the "London Air Park" at Hanworth House, where a flying school for autogyros was established. Avro were still the primary contractor, with only final assembly and flight testing at Hanworth.

James G.'s restless energy was not sated however, and in 1932 he purchased a licence from his partner Cierva to go into the autogyro business for himself, establishing the Weir Aircraft Department at the Argus Foundry, a company facility in Thornliebank.

Weir didn't want to compete with Cierva - he just wanted to put more effort into the rapidly advancing field of rotorcraft and felt he could throw his own engineering skills, and those of his company, behind it too.

But Weirs were heavy engineering concern, primarily supplying the shipbuilding industry, so James G. recruited experts around him - including daredevil motorcycle TT rider and test pilot Cyril G. Pullin and Glaswegian engineering graduate Dr. James A. J. Bennett.

But it wasn't just the family business that Weir got into aviation, his wife also got in on the game. Mora Morton Weir became one of the first (one source says *the* first) woman in the UK to get a pilot's licence.

And the Weir's built their own personal airfield on their Skeldon House estate at Barbieston Holm, outside the sleepy Ayrshire village of Dalrymple. It was rather too small for most aircraft, but perfect for the short take off and landing of the autogiro.

Weir Aircraft used Barbieston as their test airfield and a large hangar was constructed for the purposes. Weir's first aircraft, the W1, was their version of the Cierva C28 and was completed in 1933.

In 1934 they built their own first design The W-2, now in pride of place at the National Museum of Scotland. (📷CC BY-SA 3.0 Ad Meskens)

It is reputed that James G. Weir would sometimes commute to work from his home at Skeldon House to the Weir HQ at Cathcart using this autogiro, landing in the company sports fields behind the Holm Foundry.

Weir and Cierva were two companies, but acted rather like one, sharing information and key staff and incorporating Cierva's latest innovations in successive machines.

The next big innovation was Cierva's "autodynamic rotor" patent , where tilting the rotors controls the direction flight. Prior to this all autogyros required conventional aircraft control surfaces to manoeuvre. The W-3 was built with this rotor, the W-2 got it too (📷Weir Group)

The tiny W-3 was powered by an engine of Weir's own design, and incorporated Cierva's next big advancement, the "jump take-off". (📷Royal Aeronautical Society)

Cierva modified the autodynamic rotor head so that it could be driven by a shaft from the engine via a clutch, and also made innovations in the hinge system so that the rotors caused substantially less drag when they were moving opposite to the direction of flight.

Prior to this, autogyros would spin up their rotor prior to flight using a rope wound around the shaft, but this only shortened take-off. In the jump take-off, the rotor was spun up by the engine, the aircraft would "jump" off the ground...

...and the pilot switched the clutch from the rotor shaft. The propeller would begin to provide forward motion, and the energy stored in the rotor would be sufficient to keep the autogyro off the ground until it had sufficient forward airspeed for flight.

Tragically, Cierva would not live to see the first jump take-off, he died in December 1936 when a KLM airliner he was onboard crashed outside Croydon after take-off. It was Dr. J. A. J. Bennett of Weirs who would finish the work on the system, with the first jump flight in 1938.

Weirs incorporated autodynamic control and jump takeoff into a productionised version of the W-3, the W-4, but this crashed on its first take-off and was written off. Nevertheless, Weirs readied themselves to launch their £500 autogyro on the commercial market.

But the pace of advancement in the field rotorcraft was relentless, and the W-4 was obsolescent before it even got going. At the Air Ministry's request, Weir abandoned autogyros and turned their attention to helicopters.

Why the rush? Because in 1936 German engineers Focke and Achgelis had perfected and flown the first practical helicopter, the Fw61 (itself using Cierva patents under licence). With breakneck speed, Weirs managed to get Focke and Achgelis licences and set about their own version.

Weirs made what was basically a scale copy of the Fw61 using parts leftover from earlier autogyro development. And so it was that, just 2 years behind the Germans, that on this day in 1938 the Weir W5 helicopter took off from a field in Ayrshire (📷Royal Aeronautical Society)

(That last photo is taken in Ayrshire, obviously) The W-5 may have been makeshift and tiny, but it did the trick and it worked. It was the 3rd practical helicopter in the world, the first in the UK, and importantly it got there before the Americans!

The W-5 made over 100 flights by 1939, and work was already underway on a bigger successor, the scaled up W-6, which first flew in 26th October 1939. on 27th, the W-6 became the first helicopter to ever carry a passenger.

The W-6 was built at the Argus Foundry in Thornliebank, and is shown here at the Weir's airfield at Barbieston, with Skeldon House in the background (📷RAF Museum)

Weir's weren't just copying the Germans though, they made advancements of their own. The problem of perfectly balancing weight variations in the rotors for instance was solved by Jack Arnott, G. & J. Weir's Chief Chemist, using a chemical milling process.

The rotors were a metal and plywood composite, and Weir's turned to the expertise in the latter material of legendary furniture makers Morris of Glasgow to build them.

And it was Weirs who advanced and demonstrated the most critical safety technique for helicopter flight - autorotation. If the engine fails, it is declutched from the rotors, and the kinetic energy stored in the latter is used to safely land the aircraft.

The W6 was the first aircraft to demonstrate autorotation, having been built with clutches that allowed the engine to be disconnected from the rotors. Otherwise, the drag of turning the engine over would cause the rotors to rapidly stop turning and the helicopter to crash

Weir kept his friends in high places from his Royal Flying Corps days, he was a personal friend of Hugh Trenchard - "Father of the RAF" and in 1940 gave his old pal Air Vice Marshall Tedder a ride in the W6

Tedder was suitably impressed and Weirs were working on the bigger W7 a 3-seater antisubmarine helicopter to designs of G. G. Pullin, the son of Cyril Pullin, Weir's early test pilot.

But this was 1940 and the Battle of Britain was about to break. In July 1940, the Air Ministry took the fateful, but requisite step, to cancel all helicopter development and focus the entire British aircraft industry on more critical work.

Weirs had at this time what was probably the largest helicopter design team in the world, and at a stroke it was disbanded. Some of the staff were able to find a home in the Cierva company (which was now almost entirely controlled by G. J. Weir anyway).

British work on helicopters continued on paper only, with G. G. Pullin, and Dr J. A. J. Bennett keeping on the Cierva payroll. And then in 1943 everything changed as the Americans got their Sikrorsky R-4 into production and the Air Ministry were panicked into playing catchup.

With the orders from the top to play catch-up again, James G. Weir re-established the Cierva Company as Cierva-Wier and got the old team back around the table.

Cierva-Weir's first aircraft was the W9, arguably a much more advanced machine than the Sikorsky, with automatic "collective control" (which controls lift from the blades) and the worlds first NOTAR (no tail rotor) system, using the engine exhaust for anti-torque control

The W9 first flew in 1945 and was publicly demonstrated in 1946 before being written off in a crash.

But Cierva-Weir weren't going to stop there, and in 1945 started work on the enormous W11 "Air Horse" military airlifter, the first (and I think the only) three-rotor helicopter (📷 IMW ATP 17007D).

The W11 first flew in December 1948, funded by the Colonial Office as a potential crop-sprayer for use in Africa for the "Groundnut Scheme", but was delayed when the subcontractor Cunliffe-Owen decided to exit the aircraft industry.

The W11's construction was transferred to Saunders Roe Aircraft ("Saro") and again it was H. Morris & Co. of Glasgow who provided the composite wooden structure for the rotors.

The promising W11 project came to a tragic end in 1950 when the second prototype G-ALCV crashed killing Weir and Cierva's longtime test pilot Alan Marsh, arguably the most experienced rotorcraft pilot in the world at the time, and 2 other crew.

From the wreckage of the W9 and W11 schemes came the more practical and conventional Cierva-Weir W14 "skeeter", a lightweight helicopter for general transport and aerial observation duties (📷CC By-SA 3.0 RuthAS)

The Skeeter beat a rival design from old Weir and Cierva protégé, Dr. J. A. J. Bennett, the jet-powered Fairey Ultralight, and won British and German military contracts.

Just short of 100 Skeeters were built for the RAF, Royal Navy and German Bundeswehr and it later served wit the Portuguese Air Force.

J. G. Weir sold Weir-Cierva to Saunders Roe, the primary subcontractor, in 1951 after the crash of the W11 and death of his friend Alan Marsh. Skeeters are usually called the Saro Skeeter. Saro continued to develop the design into a larger model, the P351 (📷 CC By-SA 3.0 TSRL)

In 1959, Saro's helicopter interests were bought by the Westland Company, who would mature the P351 into production models that they would build in large quantities as the Westland Wasp (📷CC By-SA 4.0 Mike Freer) and Westland Scout (📷CC By-SA 2.0 Tim Felce).

Weir's contributions to the development of the helicopter were hugely important, and may be largely forgotten to all but aviation buffs, but there's something of this story you may unknowingly already be familiar with...

...familiar, that is, if you're a fan of the work of this man.

Because what is it that chases Robert Donat's Richard Hannay across the moors of Scotland in the 1935 (and best) version of The 39 Steps? None other than a Cierva autogyro.

The aircraft in question is a Cierva C.30, also known as the Avro 671 Rota, (📷CC BY-2.5 Asterion). Legend says it was flown by James G. Weir himself for the film, but it's actually a scale model.

Hitchcock was either acquainted with James G. Weir, or became familiar with the eccentric industrialist's use of his personal autogyro to commute to work, and inserted the footage late on in cutting to add an additional element of something modern and threatening to the chase.

Weir lived to a ripe old age and died at Skeldon House in 1973. Together with Cierva and the team of experts he assembled, his contributions to rotary winged flight include;

✅ Autodynamic control of flight

✅ "Jump start" takeoffs

✅ Autodynamic control of flight

✅ "Jump start" takeoffs

✅ The first cross-channel Autogyro flight

✅ The first British, and world's 3rd, flying helicopter

✅ The first helicopter to land by autorotation

✅ The first "no tail rotor" helicopter

✅ The first triple rotor helicopter

✅ The first British, and world's 3rd, flying helicopter

✅ The first helicopter to land by autorotation

✅ The first "no tail rotor" helicopter

✅ The first triple rotor helicopter

Had things not played out differently, there's every chance that Cathcart or Thornliebank would have become a world centre of helicopter development and production... 🔚

If you want to read more and better detail on the Scottish contribution to rotary winged flight, then there's an excellent paper by Prof. Dugald Cameron and Dr. Douglas Thomson of the University of Glasgow you can download for free here; researchgate.net/publication/29…

Read this thread as a single, unrolled page here; threadreaderapp.com/thread/1534103…

Footnote. One of Cierva's main contemporaries and rivals was the Austrian engineer Raoul Hafner, who opened his business right next to Cierva's at the London Air Park. Hafner was bankrolled by none other than Scottish Industrialist Jack Coats, of J &. P. Coats of Paisley.

Footnote 2. After selling the Weir's Cierva holdings to Saro in 1951, James G. didn't lose interest in rotary winged aircraft entirely. He kept up an association with figures in the industry and continued to develop and test his own ideas.

In 1961, he engaged with, and invested in, engineer J. S. Shapiro and his company Servotec to collaborate on designs for a new lightweight helicopter, and the interests of Weir and Shapiro were merged as Cierva Rotorcraft Co.

The company combined the ideas of Weir and Shapiro into a futuristic looking prototype, the CR Twin, or "Grasshopper". It flew first in 1969 and 3 were built, but Weir's death in 1973 saw funding evaporate and it got no further.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh