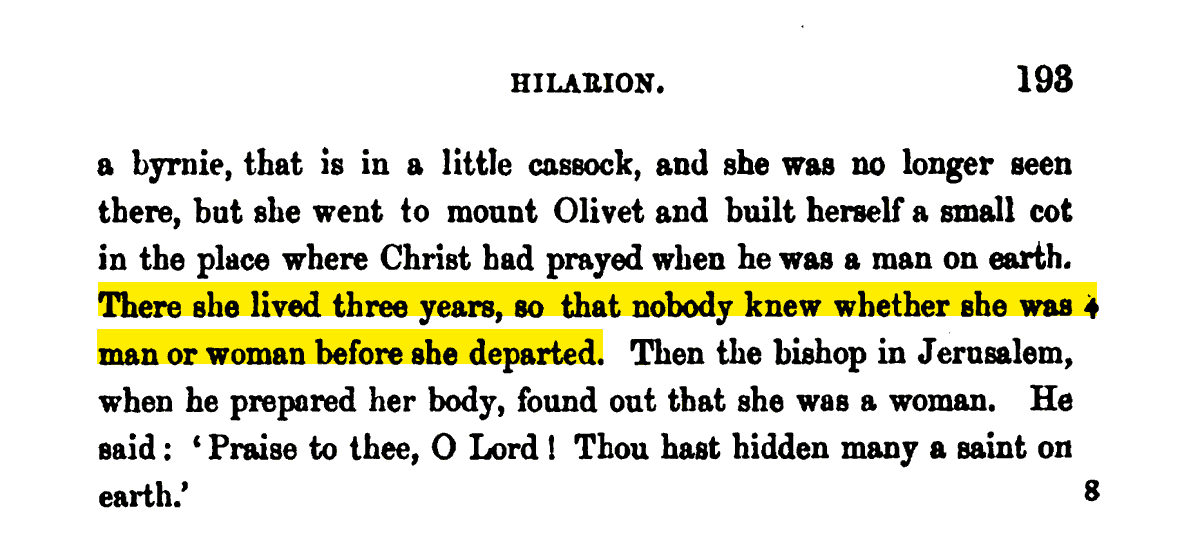

Quick #MedievalTwitter thread about saints in the 9th-century Old English Martyrology that defy the gender binary.

Up first: St. Pelagia, who lived in such a manner that no one knew if Pelagia "was man or woman"

Up first: St. Pelagia, who lived in such a manner that no one knew if Pelagia "was man or woman"

Now, the pronouns there are "she/her". However, if we peak at the Old English original, the spelling shifts slightly during the nonbinary period: "hio" instead of "heo." Remember that difference. We will see it again.

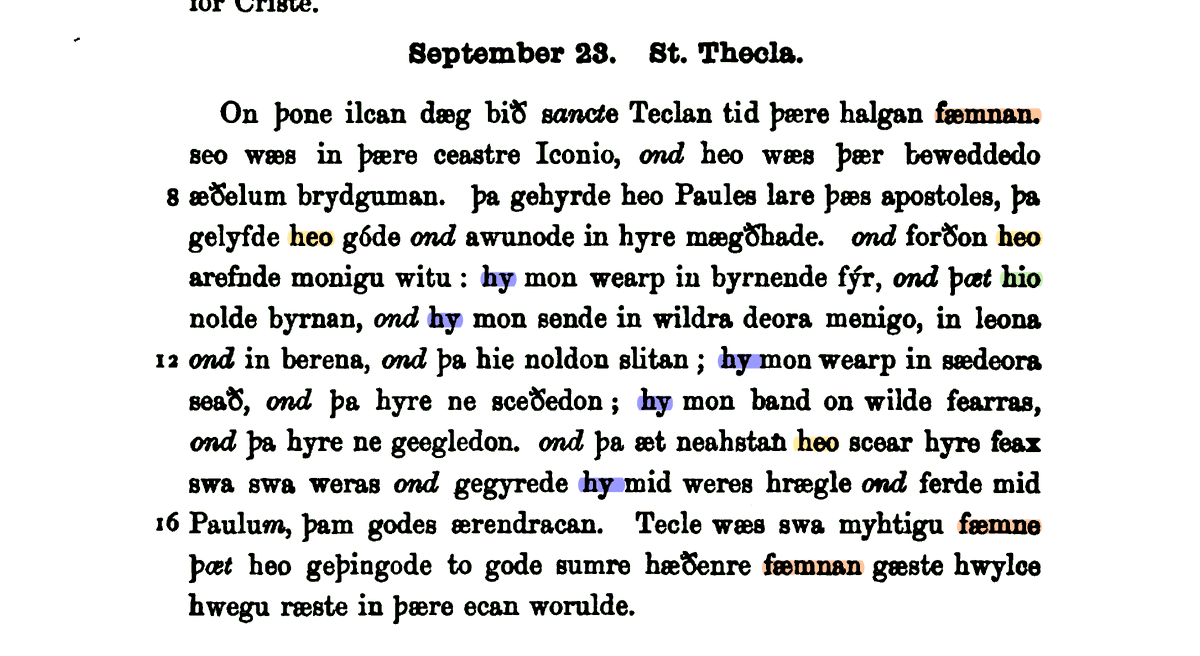

Meet St. Thecla! Thecla is AFAB but goes to a monastery and becomes a monk.

Now, again, female pronouns and a reference to Thecla being a "woman", right? Well.....

Now, again, female pronouns and a reference to Thecla being a "woman", right? Well.....

The Old English is weird! Thecla has a bunch of pronouns here, including both "heo" and the spelling "hio" we've seen before.

But also "hy" which is USUALLY a variation of the third-person plural pronoun "they."

The modern translator turned these all into "she/her"

But also "hy" which is USUALLY a variation of the third-person plural pronoun "they."

The modern translator turned these all into "she/her"

One other point: the word that we see translated as "woman"? It's "faemne": "virgin" or "maiden."

Now, this is normally only applied to women but I swear I've seen instances where men also were described with it.

Now, this is normally only applied to women but I swear I've seen instances where men also were described with it.

This is significant, because when the Martyrology writer states that Pelagia, for instance, appeared to be neither man nor woman, and the word used for "woman" there is "wif" [woman], not "faemne"

An old favorite, St. Eugenia, is up next. Eugenia is AFAB but lives as a monk for a while, before moving to a woman's convent and living as a nun.

This one is interesting, because the Martyrology author *seems* to be using "faemne" to mean "woman" here, saying that "nobody could find out that [Eugenia] was a faemne" in the monastery.

The pronouns are consistently "heo."

The pronouns are consistently "heo."

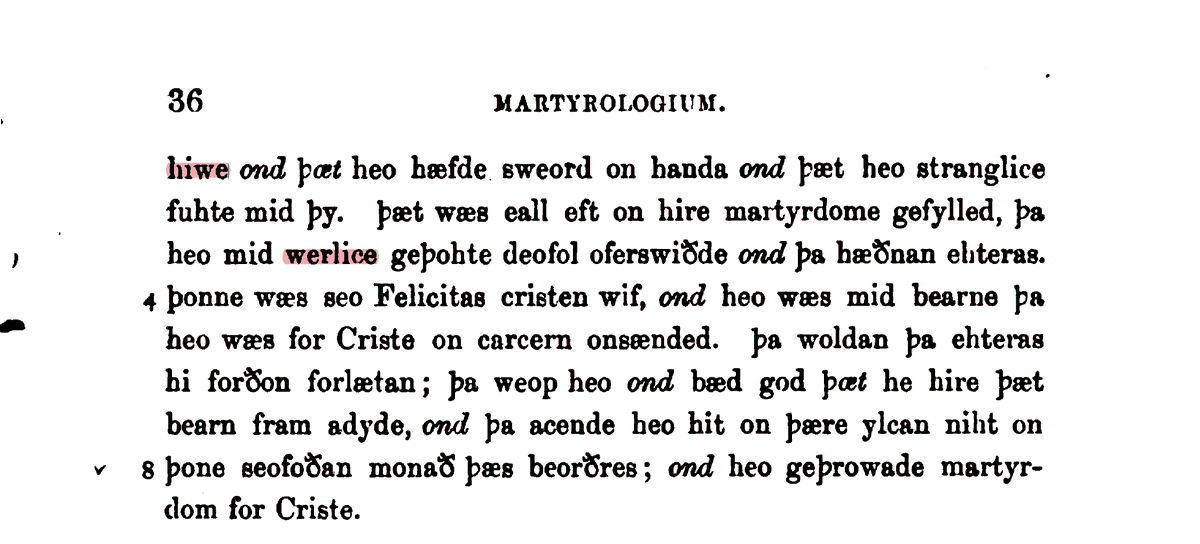

Last one is St. Perpetua, an AFAB saint who dreamed in childhood of having "the appearance of a man" and a sword that Perpetua fought with valiantly.

Perpetua fulfilled this later in life by suffering a "manly" martyrdom.

Perpetua fulfilled this later in life by suffering a "manly" martyrdom.

What's striking about Perpetua--like most of these examples--is that the miracle that ensures Perpetua's sainthood is achieving some version of manhood.

What makes Perpetua a saint for the author is that Perpetua dreamed of looking and acting like a man, then achieved that.

What makes Perpetua a saint for the author is that Perpetua dreamed of looking and acting like a man, then achieved that.

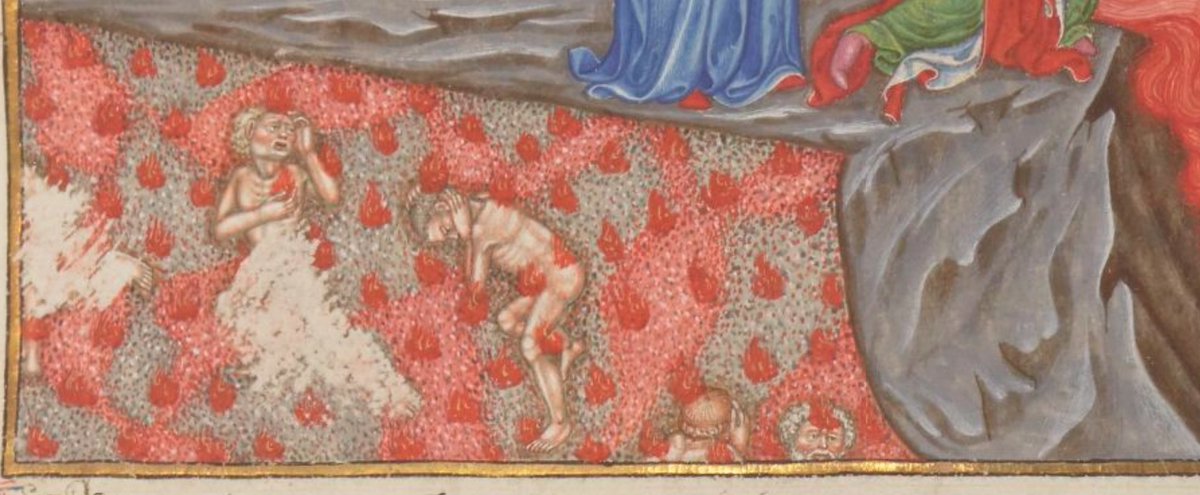

The Old English here make me think of something @MxComan said about gender and color in medieval artwork, which is that men tend to be portrayed as having slightly darker skin than women.

The Old English word translated as "appearance" is "hiwe": literally "hue"

The Old English word translated as "appearance" is "hiwe": literally "hue"

"Hiwe" absolutely can mean "appearance" in context, but it's first and foremost a reference to color.

Perpetua dreams of having a man's color.

Perpetua dreams of having a man's color.

These saints' lives have been traditionally read as lives of women, women who either escape patriarchy through "disguise" as men or whose adoption of manly characteristics is lauded because, again, of patriarchy.

But there's other possibilities for reading.

But there's other possibilities for reading.

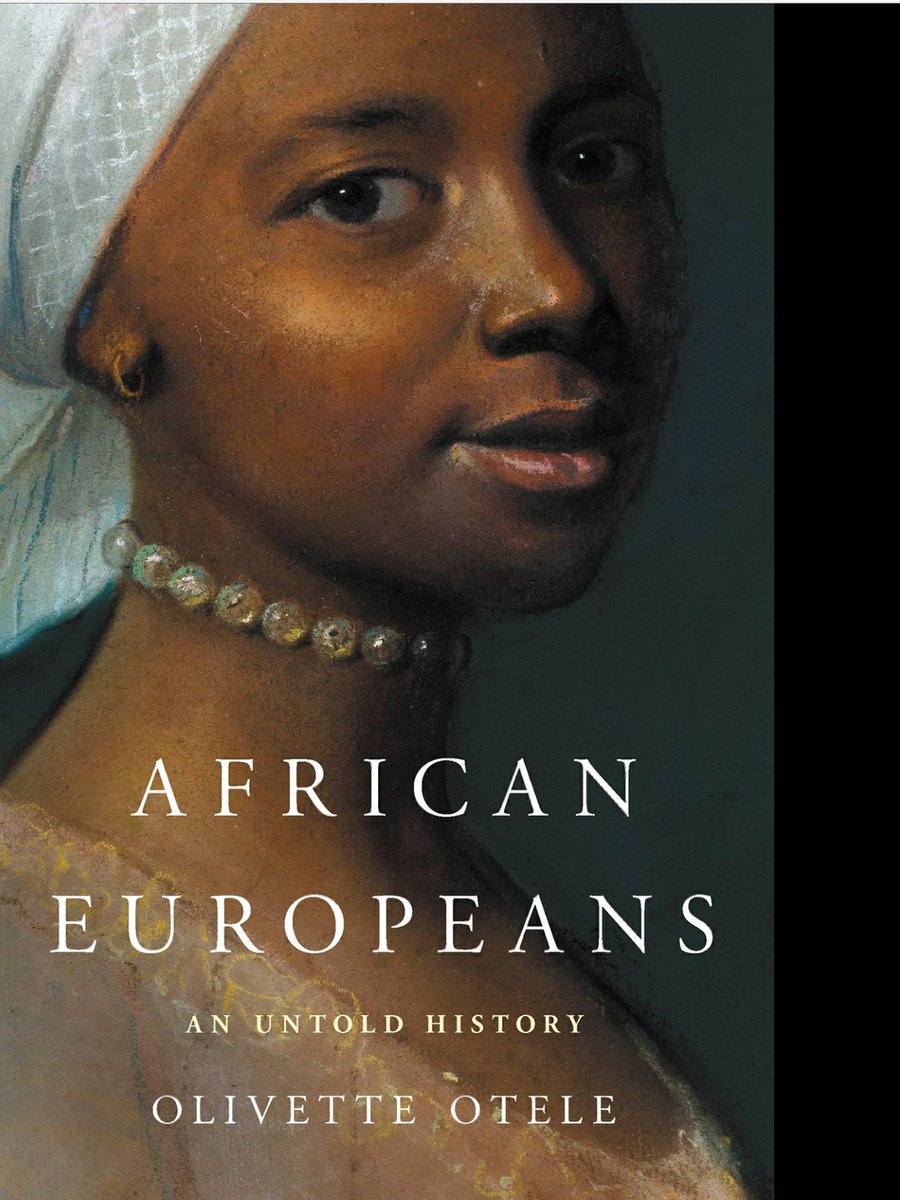

Trans and genderqueer readings of saints have flourished in the last few years, driven by amazing books like this one: degruyter.com/document/doi/1…

Old English studies has had less of this work, but there's so many texts like this where complex things are happening with gender, including at the level of vocabulary and pronouns.

I've mentioned OE texts that carefully switch pronouns for these tales:

I've mentioned OE texts that carefully switch pronouns for these tales:

https://twitter.com/erik_kaars/status/1143478441582452737

It's not that trans, genderqueer, and nonbinary lives are new. It's that any hints of them were edited out by modern translators like this one.

There's a lot of work to be done recovering the possible traces of such lives in texts like the Old English Martyrology.

There's a lot of work to be done recovering the possible traces of such lives in texts like the Old English Martyrology.

I hate being so self-promotiony, but if you're interested in how modern translators and scholars have edited out or denied queer and trans themes in medieval lit, I have a new article on the topic, currently available for free to download:

https://twitter.com/erik_kaars/status/1533787571679023104

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh