To be great, countries must have strong education, which is not just teaching knowledge and skills, but also strong character, civility and work ethic. (1/8)

These are typically taught in the family, schools and religious institutions. That provides a healthy respect for rules and laws, order within society, low corruption, and enables them to unite behind a common purpose and work well together. (2/8)

As they do this, they increasingly shift from producing basic products to innovating and inventing new technologies. (3/8)

For example, the Dutch rose to defeat the Habsburg empire and become superbly educated. They became so inventive that they came up with a quarter of all major inventions in the world. (4/8)

The most important of which was the invention of ships that could travel around the world to collect great riches, and the invention of capitalism as we know it today to finance those voyages. (5/8)

They, like all leading empires, enhance their thinking by being open to the best thinking in the world. (6/8)

As a result, the people in the country become more productive and more competitive in world markets, which shows up in their growing economic output and rising share of world trade. (7/8)

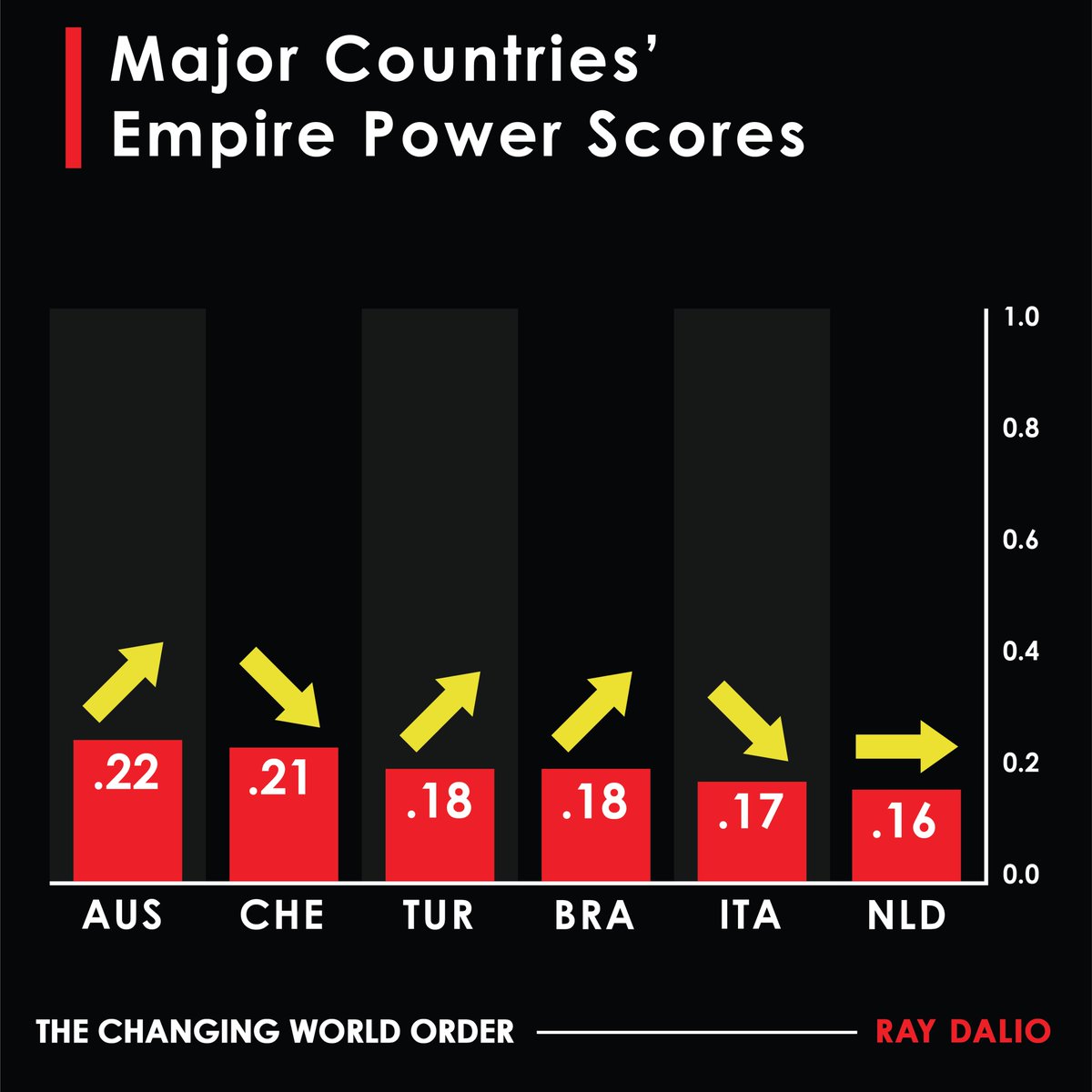

You can watch my free video on the Changing World Order to learn more and understand how the past can teach us about what’s happening now: #changingworldorder (8/8)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh